Author: Jelena Gvozdic

Welcome to Part 2 of The legacy of wartime propaganda by PROV Access Services Officer Jelena Gvozdic.

Revisit Part 1 here.

The long shadow of atrocity propaganda: a new WWI scholarship emerges

The German invasion of Belgium was certainly violent and it was passionately debated, well after the end of the war. 6,500 civilians perished in August 1914; some historians estimate this took place in the space of 10 days (Horne 2002). There were even larger instances of violence against civilians, up until 1918, in other areas affected by the war.

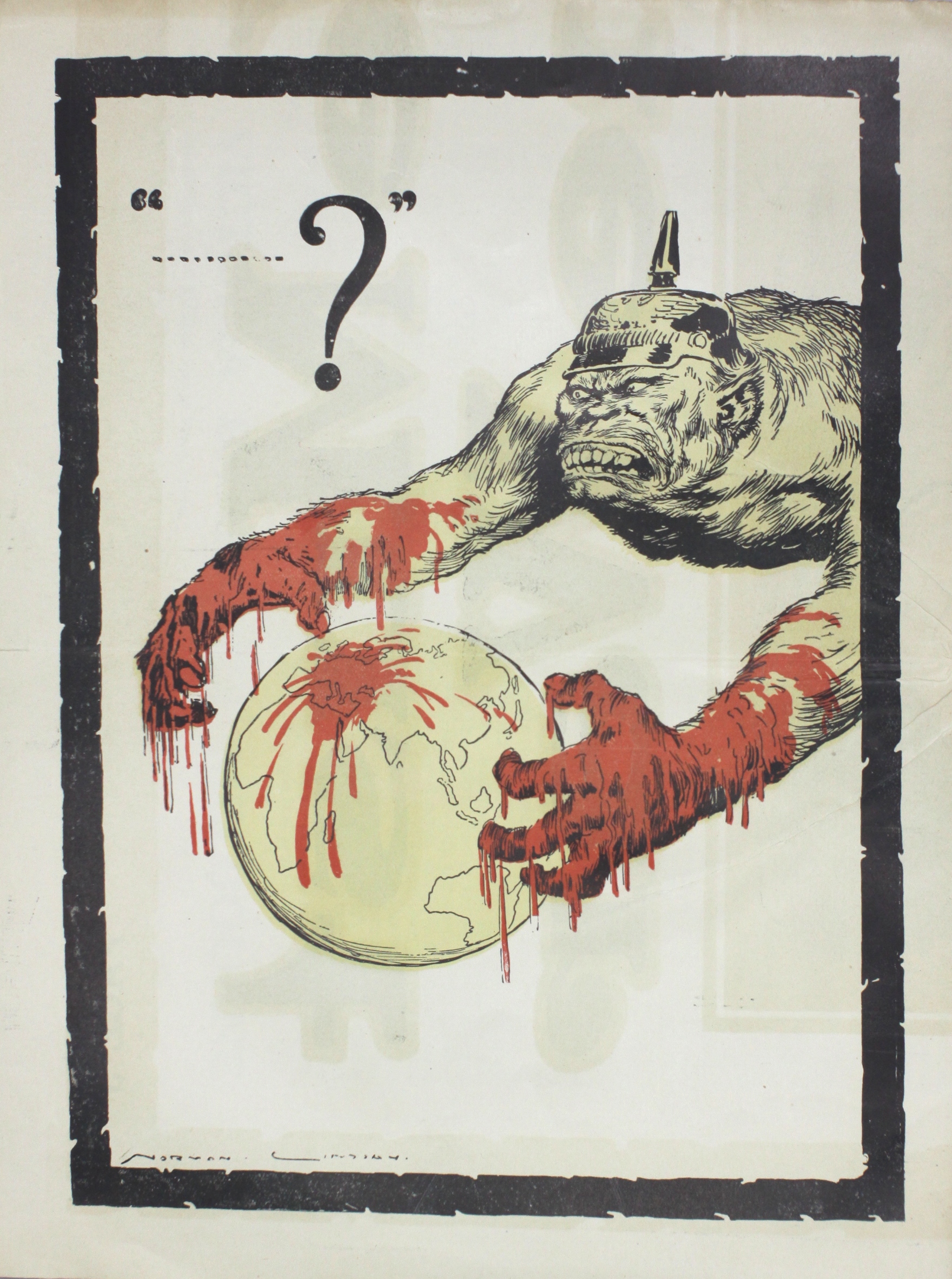

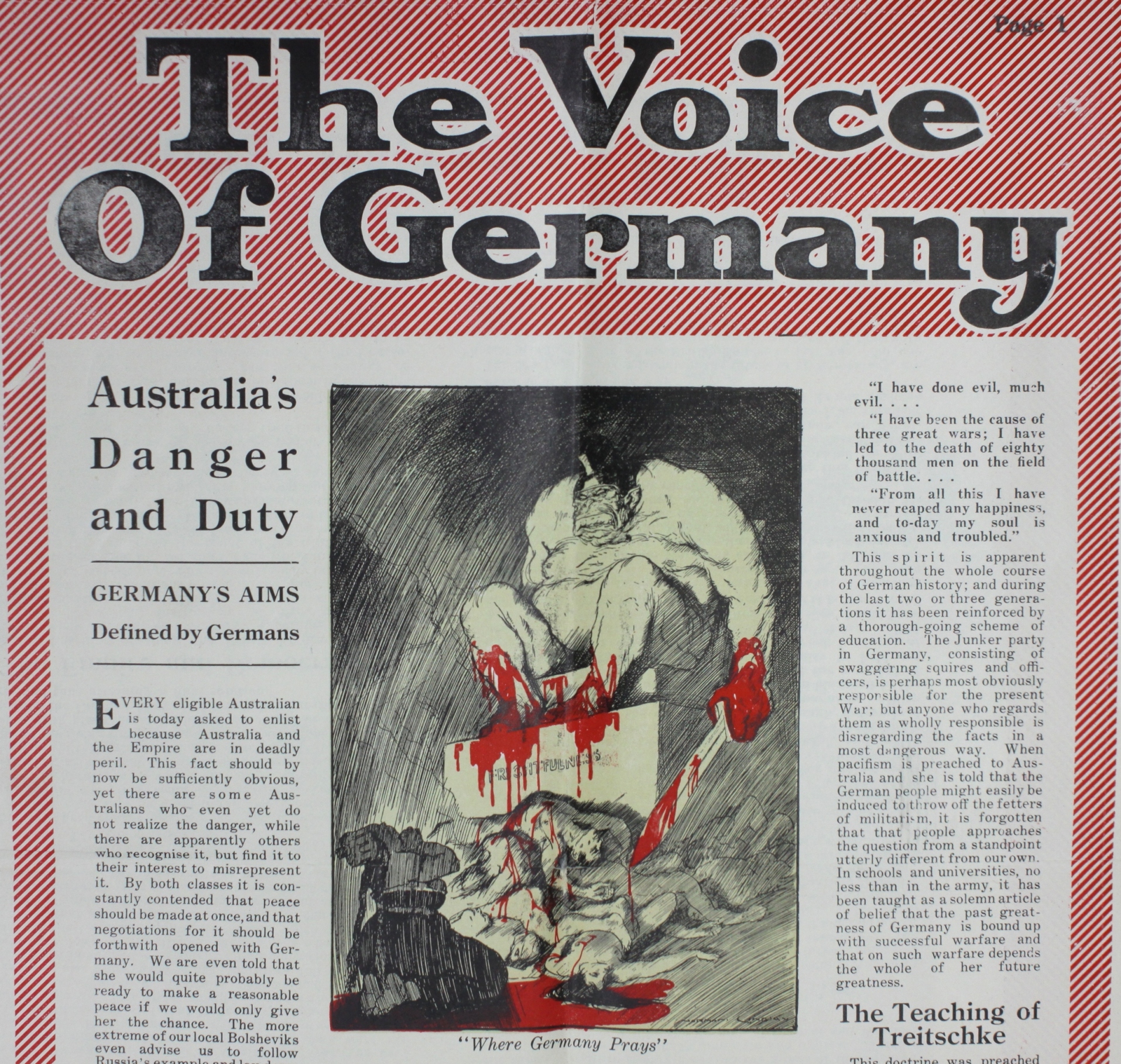

Exaggeration on the Allied side in recounting the occupation is obvious – to demonise the enemy it was necessary to repeat stories of victimised and mutilated women and children. Horrid tales that had little or no factual grounding often made their way through to the press and literature of the time, including official speeches, publications and pamphlets, causing international outrage.

Imagery with the bestial Hun VPRS 3183/P0 Unit 132.

After the war, many people considered the German atrocities of 1914, and others which took place in different regions, to be nothing more than Allied propaganda. Condemnation of the war had led people to question what fuelled the fighting, to the point where many believed the violent events to have been a mere creation (Schaepdrijver). Recent historiography has revealed that the most brutal stories in Belgium were in fact “mythic representations of real distress originating from traumatised civilian refugees” (Horne 2002, p.51) such as fabricated tales of Germans using Allied troops’ bodies to produce soap and animal feed. Historians John Horne and Alan Kramer wrote in German Atrocities 1914 that although there were many myths and tales, violence against Belgian civilians was not a “figment” of propaganda.

The suffering of civilians was appropriated by propagandists to justify the war while it was taking place, but then described as mere lies once it had ended and millions of people needed to come to terms with the great destruction and loss, brought on by the conflict. This “counter myth” of governments manipulating their people to wage a war through repackaging and marketing has persisted among popular consciousness in many Allied countries, as well as other regions (for different reasons).

German monster on a bloodied pillar of “frightfulness” with a pile of corpses at the bottom – the caption reads “Where Germany Prays” vprs 3183/P0 / 132.

Pacifists from the 1920s and onwards, had a strong desire “to discredit a war that had cost so many male lives [but in doing so they] contributed to the erasure of another set of victims – those men, women and children whose suffering had been exploited to market the war” (Gullace, 2011). Historians have talked about the shadow of WWI wartime propaganda and the impact of the interwar period on the collective remembrance of WWI and the course of the Second World War (see Fox). An analytical focus on “propaganda” with virtually no reference to the actual war crimes or events that inspired these manipulations does a complete disservice to the telling of any history (Gullace, 2011).

What we cannot forget during the centenary program is that WWI itself was a great atrocity (as is any war) where many suffered - not just those who fought in the trenches. The course of events that took place during the war was complex, devastating the populations of a number of countries. Civilian casualties should never be overlooked when remembering this global conflict. Over 7 million civilians died between 1914-1918 from military action, crimes against humanity, malnutrition or disease. The re-appraisal of WW1 propaganda and its central motifs, which really only started in the 1990s, has welcomed a new scholarship exposing many truths. It shouldn’t, however, ignore an analysis of the realities that took place in regions other than Western Europe.

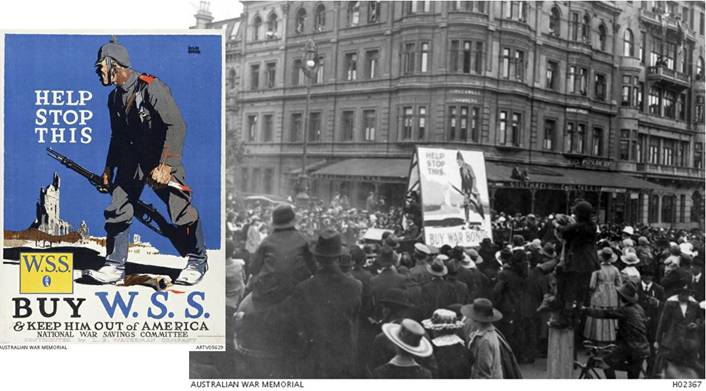

Crowd gathers in Melbourne 1918 in a procession of returned troops who are accompanied by a poster requesting people to “Buy War Bonds”. A clearer image of an American poster is shown to the left. (Source: Australian War Memorial, ARTV05629 & H02367)

The pamphlets in PROV’s collection are interesting pieces of history; through them we can look at popular propaganda themes and ideas. In addition, by putting them in context, we can learn about the legacy of WWI atrocity propaganda and how it continued to infuse itself into post WWI history. We are all connected to the First World War in one way or another - 100 years on from one of the deadliest conflicts in human history the destruction of war must not become an abstract thought. Understanding the course and causes of WWI must not become irrelevant nor inundated with glorified stories of military battles. We cannot learn from this conflict if we stop re-evaluating and examining the beliefs we have accepted as historical truths, or if we forget the great horrors of war.

Sources (Parts 1 & 2):

Australian War Memorial, “recto: The Gospel of Frightfulness, The Voice of Germany, Hurry! verso: The peril to Australia” poster, ARTV00037, accessed online http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/ARTV00037/

Fox, J, “The legacy of World War One propaganda”, British Library, http://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/the-legacy-of-world-war-one-propaganda

Gullace, N.F. 2011, “Allied Propaganda and World War I: Interwar Legacies, Media Studies, and the Politics of War Guilt”, History Compass, 9, 9, pp.686-700

Horne, J. 2002, “German atrocities, 1914 fact, fantasy or fabrication?”, History Today, 52, 4, pp.47-53

Horne, J. & Kramer, A., 2001, German Atrocities 1914: A History of Denial, Yale

Schaepdrijver, Sophia De, “The Long Shadow of the ‘German Atrocities’ of 1914”, British Library, http://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/historiography-atrocities-the-long-shadow

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples