Last updated:

Refereed articles

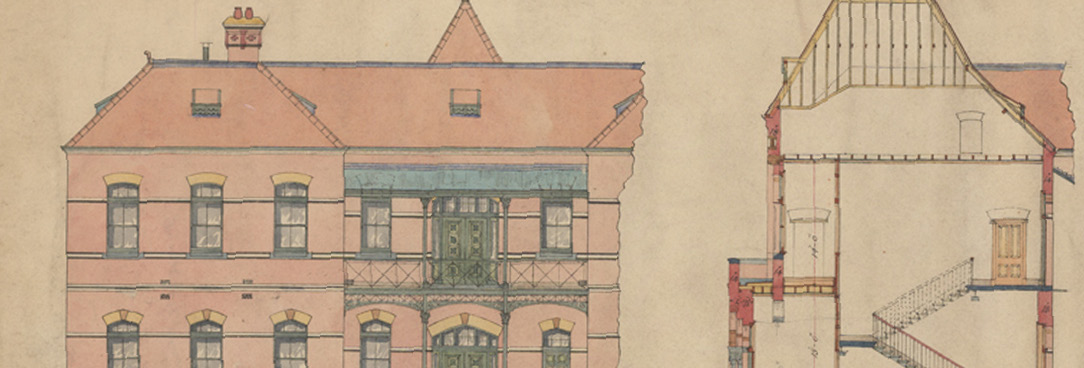

The City Morgue in Colonial Melbourne

Expand SummaryThe idea of a central morgue where dead bodies would be kept for identification and inquest was a new one in the urban culture of the British Empire of the mid-nineteenth century. Inquests up to that point took place in public houses, and bodies awaiting inquest were stored in outbuildings. A central morgue in Melbourne was first utilised in the 1850s and by the 1890s had become the main site of coronial inquests. The call for a morgue was partly a response to the desire of the government to identify its deceased members and label their deaths, and partly a requirement of the climate. Traditional practices, rooted in localism, were inefficient in a growing colonial society with hot summers. The surveillance of the dead was common in French and English societies, but was given particular emphasis in a town experiencing a gold-rush population boom. Changing ideas about what was acceptable in polite society also played a part. Identification, decency and health, therefore, provided varying motivation for this radical departure from local English practice. However, the morgue occupied an ambiguous place within the bureaucracy of the day. And like its Paris counterpart, it was sequestered, for a period at the end of the nineteenth century at least, as a lurid but nonetheless acceptable place of spectacle and macabre titillation.

Motor-Car Regulation and the Defeat of Victoria's 1905 Motor-Car Bill

Expand SummaryAt the turn of the twentieth century some upper-class Victorians became motorists; consequently, for the first time ever, regulation and policing intersected with this class of society. By 1905 so many concerns had been raised about compromised public order and safety that the Victorian State Government attempted to implement a Motor Car Bill based on its English predecessor (1903). Wealthy motorists possessed power and influence, however, which contributed to the postponement of legislation until 1910. Additionally, parliamentarians were drawn from the same social class as motorists, and, in creating regulation, they were potentially regulating their peers, colleagues and friends. The private motor-car also brought with it new issues of civil liberty and responsibility. Finding a balance between the two continued to be a problem, as private transport gradually became affordable for middle- and working-class people, and both the number of regulations and the power of the motoring lobby increased.

Stories from the Nineteenth-Century Castlemaine Police Courts

Expand SummaryThis paper uses the records of the Castlemaine, Chewton and Fryerstown police courts from 1860 to the 1890s in order to examine the ways that people sought to make themselves a home after the main goldrushes had finished in the district. ‘Home’ is taken to mean a place that offers security, comfort and a sense of belonging – more than simply a house. The paper briefly considers the ways that the courts worked both for and against the various interests of claimants and then looks in more depth at some of the family law cases that came before the court. These cases reveal that the struggle to make a home was often carried on even within the four walls of a house.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples