Last updated:

‘Quarry and stone research methods: looking for holes in history’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 15, 2016–2017. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Susan Walter.

This is a peer reviewed article.

Quarries, quarrying and stone use in Victoria were an essential part of Victoria’s development and built heritage, but are infrequently considered in historical works. The formation in 2012 of the Heritage Stone Task Group, which will oversee the international recognition of Global Heritage Stone Resources, has the potential to reverse this situation, with nominations for Sydney sandstone and Victorian bluestone already underway. Reasons for researching the subject of building stone can also include analyses of historic landscapes, impact of former land disturbance on current state and local planning issues, an interest in local or family history where quarrying and stone use feature strongly, or heritage issues relating to restoration works. The histories of many of Australia’s iconic, and less well-known building stones, are however poorly documented. Many quarries were on private land and mining law did not generally cover quarrying activity until well into the twentieth century, making such records scarce. Quarries on public land can be explored and researched via public records accessed through the Public Record Office Victoria catalogue and the Victoria Government Gazette. Public records can also reveal quarrying on private land that might otherwise go unrecorded. This paper examines the means by which the history of stone and stone quarries in Victoria can be researched through public archives. By contributing to the understanding of landscape history, building stone heritage and land history research methods, it demonstrates that there is a wealth of knowledge to be gained from examining quarrying history, and assisting the global recognition of our local stones.

The first details of a proposed Global Heritage Stone Resource (GHSR) designation that would recognise 'natural stone resources that have achieved widespread utilisation in human culture' were made public in 2008.[1] Since then, the concept has been officially accepted by the International Union of Geological Sciences and the International Association for Engineering Geology and the Environment. The formation of the Heritage Stone Task Group (HSTG) and its approved management scheme followed in 2012; its function being 'to accommodate the proposal and to endorse international procedures that formally recognise the GHSR designation'. In 2015 a nomination for Portland stone from Dorset, England was accepted, with a nomination for Sydney sandstone being one of several others currently being considered.[2] Work to nominate Victorian bluestone is being undertaken by the author.

While nominations must include both scientific and historical information on the stone, in addition to its sources and uses, there is a noticeable dearth of detailed published works on stones originating from Victoria that would meet the requirements of the HSTG.[3] One of the objectives of the HSTG is to facilitate the identification of stone sources and preservation of quarry sites to ensure materials are available for future restoration works. Obtaining technical information, however, may require destructive sampling, but there is also a need for reference samples from quarries with which to compare the test results. Alan Spry’s 1988 study, Building stone in Melbourne, records the uses of a wide range of stones in inner Melbourne to assist in stone identification and provide a literary resource for restoration projects.[4] What is needed are detailed histories, including technical data, of source quarries themselves to provide both spatial and temporal use of stone to assist in narrowing down a list of potential sources within a defined region. By concentrating on a single stone type, the 2014 book, Sydney’s hard rock story: the cultural heritage of trachyte, fills such a gap and has made a significant contribution to the understanding of building stone and associated land use and industrial heritage.[5]

Anyone wishing to fill the information void and document the significance of any given Victorian stone requires access to historical records of quarry sites, stone use, distribution of that use, technical information and heritage citations. There is currently no 'one-stop shop' for the history of Victorian quarries. It is a complex process of transcribing, matching, cross-referencing and interpretation that Beresford described as 'a “triangular” journey from field to archive, archive to library, and back again'.[6] The documentation of quarry histories themselves is often a challenge. Land use history, especially the move from Crown land to private land, is erratic and it is wise to cover the entire history of a site to ensure all potential material is acquired. The aim of this paper is to demonstrate a means by which this can be achieved through the example of bluestone quarries around Malmsbury where an important stone resource was harvested for well over 70 years. This method is applicable in other localities where stone was quarried and thus has a direct relevance to stones sourced from Victoria and still present in the built heritage of a much broader landscape.

Getting started

The basic tools for the job are parish maps, geological maps, archived aerial photographs, probates, inquests, Crown land files, newspapers, rate books, and government gazettes. This rather simplified list, however, hides other problems a researcher will encounter. Take the last three items for example. Rate books may or may not be lodged with Public Record Office Victoria (PROV)—in the case of Malmsbury Borough (1861–1915) they are not—but in most cases they have not been digitised or transcribed.[7] Luckily many years ago Malmsbury Historical Society acquired some photocopies of an incomplete run of years and their volunteers have been transcribing the key details into a database which covers 1861–1872, and 1879–1894.[8] In addition to this, the digitised Victoria Government Gazette (VGG) available online via the State Library Victoria (SLV) can only be searched based on the printed index in each volume, so land parish names or the names of people acquiring licences to occupy Crown land for quarrying can only be found by manually examining one edition at a time.[9] Here, however, the valuable work of Archive Digital Books should be applauded for their digitisation of these volumes with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and word search functions that do enable such data to be found in a timely manner.[10] Only the 1914–18 period of the Kyneton newspapers (Malmsbury did not have its own newspaper) are available on the National Library of Australia’s digitised newspapers website, Trove, so newspaper-based research outside of this period is time consuming and cumbersome, but nevertheless rewarding. The other tools listed are far more readily available, either from PROV, SLV or the Victorian Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources websites, or a visit to an archive centre such as the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning’s aerial photography library at Laverton.[11]

Quarrying on private land

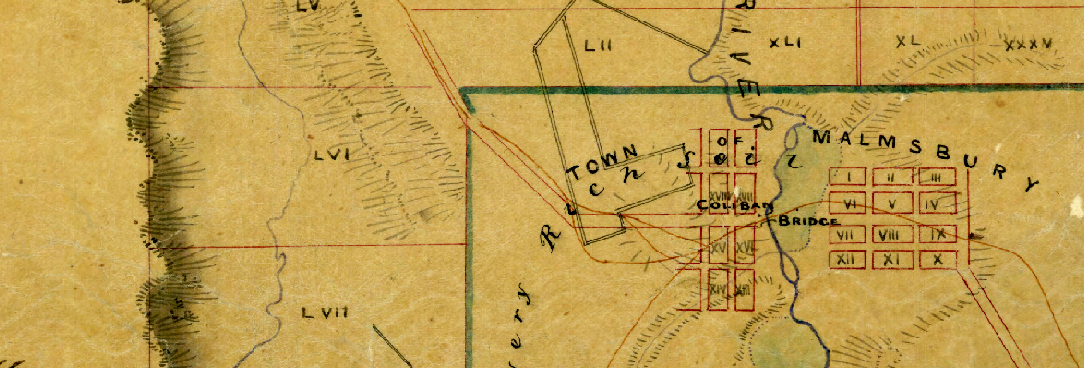

On Ernest Lidgey’s 1894 Malmsbury and Lauriston Gold Field map, the location of a number of quarries was recorded within the parishes of Edgecombe and Lauriston, and the township of Malmsbury.[12] Examining the corresponding Edgecombe and Lauriston parish maps reveals that the majority of Crown land was sold in the 1850s and the rest in the 1860s.[13] Unlike mining, quarrying on private land did not require any form of licence until well into the twentieth century, so the history of such quarrying is hidden in private land records such as the Registrar General’s Office (RGO) 'Old' or 'General Law' memorials and Torrens titles. In the case of Edgecombe and Lauriston parishes, it is mostly the former as the land sales pre-date the 1862 introduction of Torrens titles.[14] One also has to consider the development of townships after they are first surveyed. In the case of Malmsbury, which is mostly in the Parish of Edgecombe (the south-east portion is in Lauriston parish), a township 'reserve' was surveyed and marked out in 1851, but it took many more decades for the majority of land to be alienated from the Crown, so some quarrying sites may be found through Crown land archives.[15]

Taking Portions 25 and 34 of Edgecombe, for example, which were purchased at a Crown land auction by Richard Brodie in 1852 (Figure 1), we can see that Lidgey recorded two quarry sites on portion 34, one of which is named 'Ryan’s Quarry' (Figure 2).[16] A search of RGO land records failed to show any sign of quarrying leases being registered for this land between 1852 and 1877 which indicates that either such leases did not exist, or they were not registered with the RGO. In fact, of over 60 properties in the parishes of Lauriston, Edgecombe and Malmsbury researched in this way, only one registered quarry lease was found. This was between quarrymen Charles Mailler and Michael Woods and the owner Mary Olive in 1887 for five acres in the Parish of Lauriston.[17] When Richard Brodie died in 1872, his probate records described the two allotments as 'Spring Farm', but by February 1874 when the land was transferred to his executors, and in July 1875 when they decided to sell the property, it was advertised as 'Quarry Farm'.[18]

The new owner was Joseph Shilton, and he had the land transferred to a Torrens title in 1876 under the Transfer of Land Act 1862.[19] There is no apparent record of Shilton residing in or around Malmsbury and of his four children with Fanny Sarah Skellett whom he married in Stawell in 1871, the first three were born around Stawell between 1872 and 1875 and their last in St Kilda in 1878.[20] While Malmsbury Historical Society does not have access to the 1873 to 1878 rate books, Shilton’s name does not appear in the post-1879 rate books as either an occupier (who paid the rates) or the owner. It should be noted that the habitual failure of the Malmsbury town clerk to regularly record the owners of land in the rate books, and just as often the allotment numbers of land they were paying rates for, complicates this research. It is probate records that in this case reveal more of the story. Joseph Shilton died in 1878.[21] He had been a major investor or partner in the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company and upon his death his probate was granted to his widow. Joseph had real estate worth £16,000 which included allotments 25 and 34 in the Parish of Edgecombe (160 acres valued at £480) which was let to Mr Sullivan for £45 per annum. He also had an interest in the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company of Footscray worth £3,245 and liabilities which included an overdraft of £3,000 with the London Chartered Bank, Melbourne, with respect of the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company for which Joseph Shilton with others became personally liable. James O’Sullivan does appear in the Malmsbury rate books as occupying a house and farm in Edgecombe parish, or on Parish Boundary Road (currently called Malmsbury East Road), and between 1884 and 1892 this was recorded as being portion 34, but the owner is frequently not recorded.[22]

In 1876, Angus Mckay, a wagon driver employed by Hugh Milvain at Malmsbury to cart stone from quarries to the Malmsbury Station, was found dead beside his wagon at Malmsbury.[23] A short time earlier he had left a quarry, owned by the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company, however the newspapers also recorded the accident as being on the farm of James Sullivan and as Sampson’s quarry.[24]

An 1873 report by Robert Brough Smyth on mining and mineral statistics, shows that by that year, the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company was primarily sourcing its bluestone for sawing at the Footscray plant from quarries at Malmsbury.[25] The fact that Fanny Shilton kept the land for a number of years implies that this permitted the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company to harvest the land for bluestone until the company was wound up in 1882.[26] The land was sold to Alexander Hardie in 1889, and he continued to lease it out to James O’Sullivan until at least 1894.[27] Hardie then leased the farm out to Owen McAree, but Hardie died in 1899 and his executors sold the land to William Hall Fernie the same year, with McAree continuing his occupation of the site.[28] The probate makes no mention of a quarry on the land, however the sale notice in the Argus records that 'on this property is a first-class quarry being worked, 5 [shillings] per week being paid to the vendor for each man engaged'.[29] The probate of William Fernie, who died in 1904, also makes no mention of the quarry, but upon the death of McAree’s son, Owen Joseph McAree, also in 1904, the newspapers recorded that the son had engaged in farming and quarrying pursuits.[30]

Despite all this research, no evidence can be found that links anyone named Ryan with this quarry site. Did Lidgey get his information wrong? The quarries marked as 'Mailers' on allotment 33, and 'White' and 'Davis' on allotment 26, both just north of allotment 34, have a similar story—rigorous searches failed to locate any link between this land and local quarrymen Charles Mailler, John White (or his sons Edward Pearce White and William John White) and anyone by the name of Davis.[31] It is possible that a blanket search of local newspapers may reveal more, and prove these links, but for now this process demonstrates the need to consult a wide range of land records to construct a seemingly simple story. With evidence of quarrying activity on the land between 1874 and 1899, and perhaps later, these dates would suggest the Malmsbury bluestone structures which pre-date this will have been sourced from other quarries.

These same quarries were at risk of destruction during the construction of the Calder Highway Malmsbury bypass.[32] The eventual route bisected the quarry complex and probably destroyed some of the heritage potential of the site, however the major quarry holes were saved as a direct result of the recommendations of the consultants engaged to undertake the archaeological and heritage study. Such studies have a broad scope and limited timeframe and the information upon which the assessment was made did not include most of the above details. While the recommendations for further study have gone unheeded, there is now great potential for a deeper understanding of this quarrying landscape.

Quarrying for railways on public land

One subject matter of interest to researchers of railways and bridges is the source of stone used in the construction of railway infrastructure. Malmsbury, for example, is serviced by the Mount Alexander railway, constructed between 1858 and 1862.

While the Engineer-in-Chief’s correspondence registers reveal that much of the stone used in the Jackson’s Creek Viaduct at Sunbury was sourced from Footscray, with intentions to use the same stone at Taradale as well, at Malmsbury Viaduct the source was in the vicinity of that town.[33] The process of finding a more precise location is another example of the need for some complex research. One very brief but unhelpful reference of 1859 stated the stone was sourced from 'near the site'.[34] A railway accident in December 1863 gave better clues. A special ballast train, which was carrying a stone crushing machine, was leaving a local siding described as being 'about two miles from Malmsbury, on the east or Kyneton side of the line' that was connected to a bluestone quarry.[35] As the special train was crossing over the tracks, it was hit by the freight train from Melbourne, resulting in serious damage to both trains but not to human life.

There appears to be no surviving detailed plan of the railway’s route that might show the locations of quarries and cuttings which may have exposed usable stone. This is despite the Engineer-in-Chief’s correspondence registers repeatedly referring to such structures by number or to the portion of the specific contract in which they were located.[36] Using Google Earth, one logical starting point then is in the vicinity of the Lasslett Street bluestone road-over-rail bridge, south of the viaduct. Stone was carted as short a distance as possible to reduce costs, so why not build a crossing over the line near the quarries? The 1866 Geological Survey of Victoria quarter sheet map for Malmsbury area (Figure 3) notes the nature of the basalt rocks near this bridge, a feature which is repeated on Lidgey’s 1894 map with more recent landscape details added (Figure 4).[37] An aerial photo of 1966 (Figure 5) does indeed show the pock-marked landscape of former quarrying activity, and the features left by a short siding can be seen a short distance further south in a 1946 photograph of the same location (Figure 6).[38]

These quarry holes roughly match with allotment 9 of section 33 of Malmsbury township (Figure 7). The fact that this lot was sold in 1908, whereas the adjoining lots were sold in 1871, hints at the land being retained by the Crown for the intervening years. There are three approaches that can be taken at this point: find the VGG notice for the alienation of this land to McBride in 1908 based on the sale date, examine McBride’s probate file, or use the Catalogue of Crown Lands and Survey Files microfiche (VPRS 7312) to locate any file relevant to this land. The VGG of 23 September 1908 records that the Crown land sale of allotment 9 of section 33 was held at Woodend on 28 October 1908, with the value of improvements being £7 and offered at the upset price of £7 and 10 shillings, but this explains nothing more than the process of alienation.

An examination of the probate file of Catherine McBride from 1907 shows it was purchased by her daughter Margaret who applied to have the land sold to her at public auction.[39] Catherine had occupied the site since the death of her husband Patrick in 1905.[40] Patrick had held it by licence under section 145 of the Land Act 1901 but he had never applied to buy it. Using the VGG shows that Patrick had been occupying it since at least 1895 as a garden licence.[41] The microfiche in VPRS 7312 for Malmsbury township contains a file for this land, but it only dates from 1891 onwards.[42] The file does, however, reveal that the garden licence, originally held under section 99 of the Land Act 1890, had been transferred to McBride in 1893 by Robert Don, a known quarryman of Malmsbury, who in turn had had it converted from a quarry licence in 1891.[43] Don’s letter of application for the garden licence in 1893 states: 'I have abandoned the land under Section 99 as the quality of the stone on it is to [sic] poor'. This then gives an indication of when quarrying ceased on the land, but not when it began.

Using the date of the sale of the surrounding allotments, a 'putaway' plan dating to this time period was identified (Figure 8) and on allotment 9 there is a notation for a quarry licence with reference 73/M 25214. An earlier plan of 1865 also shows this reference number (M65B, Figure 9). This notation is a reference to the category and serial for Crown Lands Correspondence in VPRS 44, accessed by VPRS 226 and VPRS 227, where the category 73/M refers to 1873, M is the register volume (register books ran from 'A' to 'Z', then '&') and 25214 being the specific 'serial' item number. These documents are kept under a 'top numbering' system where each successive item of correspondence is given the next serial number in sequence and is added to the top of the existing file, which then is assigned the serial number of the latest piece of correspondence that was added (and so on until the file is closed). The category/serial on the microfiche for VPRS 44 is the top-most serial for the file.

If there is no specific file number known by a researcher, VPRS 226 (then VPRS 227) can be used to find references in the index under the subject 'Quarries' (such as those on page 505 of the 1873 register, which shows an entry for November of that year for 'J Prendergast, Malmsbury' with reference M page 551). At this point the microfilm roll for page 551 of the M register for 1873 in VPRS 227 is consulted to obtain the 'top' serial number. In this specific case, because it is known (register M for 1873 item 25214), VPRS 227 can be viewed without reference to VPRS 226, the entry being:

John Prendergast applies for a certain site for quarrying purposes at Malmsbury. Annotated 'Mislaid'—attached to 74/O 13019 21/7/1874.

A search of VPRS 227 and the VPRS 44 microfiche shows that this specific file is indeed 'mislaid', however the register also reveals the related reference to 74/O 13019.[44] But the 13019 file reference has no relevance to Malmsbury and perhaps this explains the 'mislaid' notation. Purely by chance, while looking in VPRS 227 for 71/D 13019, the entry for 13091 was seen stating: 'John Tyson application for sale by Auction of Allotment 9 Section 33 Malmsbury'. This, in turn, referred to serial numbers 71/D 10077 and 74/O 14381. Item 14381 shows that in 1874 John Tyson applied to have allotment 9 of section 33 sold in order to secure a supply of stone for the Malmsbury Stone Sawing Company.[45] This company was located on the Coliban River at Malmsbury and commenced operations in 1874, with Tyson being a manager and shareholder.[46] However, John Prendergast, another known quarryman, had an existing quarry licence from 1873 so Tyson’s application was refused, also confirmed by the quarry licence held by Robert Don in 1891.[47] Hence, quarrying can now be dated back to 1873. Item 10077 from 1871 shows the application John Tyson made to occupy the stone sawing works site.[48]

The 1871 'putaway' plan was surveyed by WC Reeves in July of that year. His field notebooks show his sketches and calculations for surveying sections 33 and 50 of Malmsbury (just south of section 33, also adjoining the railway—see Figure 10).[49] His observations of landscape features include the presence of a well 'made at time of railway works' and with respect to the nature of the soil, 'Section 33 portions of 5 7 8 & the whole of 9 & 10 were used for quarries for ballast in the construction of the Railways & is therefore rough & comparatively poor'. Unfortunately, Mark Amos's field notebooks from the 1865 survey and plan do not appear on the PROV catalogue. Section 50 is just north of the old railway siding reported in 1863 and the aerial photograph shows it just runs into section 50.

Michael Woods, another known Malmsbury quarryman, bought land in 1894 just east of this, being allotment 11a of section 50 (lower right in Figures 5 and 10).[50] The 1946 aerial photograph also shows signs of former quarrying on this site and a direct search of the Crown Lands and Survey Files microfiche (VPRS 7312) for Malmsbury township shows there is a file for this land.[51] The documents include a report on the condition of the land including the notation that it was 'fit for either [cereal or root crops] except 4 acres which is not fit for cultivation having been quarried for the M.A. railway'.

Hence, while there is no specific mention of the viaduct, this portion of Malmsbury, now privately owned, was Crown land being quarried at the time of the railways, and would appear to be the most likely source of the stone used. It should also be noted, though, that in 1860, Cornish & Bruce the contractors for the railway, wrote to WB Hull informing him of the provisions made for ashlar stone for the Taradale viaduct sourced from the quarries at Malmsbury 'including private land'.[52] All attempts to determine which private land was quarried, however, have so far met with a 'stone wall'.

VPRS 44 holds numerous items of similar material on quarries at many other Victorian places on a variety of stone types. Quick access to some of these can be found in the VGG notices for lands temporarily reserved for the purposes of 'procuring stone' by councils or by quarrying licence, each entry in the gazette bearing the reference number from this series of records. Two examples of this are those gazetted for Yarrowee in 1867 (67/O 4166) and Burrumbeet in 1868 (67/O 8383).[53] While the microfiche for VPRS 44 can be referred to quickly to determine if these sites are filed under these specific serial numbers, if they are absent VPRS 226 and VPRS 227 may need to be consulted for any subsequent references. The VGG also contains half-yearly reports of early fledgling municipal councils which mention their requests to have the state government set aside these reserves. In the case of Brighton Council, their bluestone quarry reserve was located near Williamstown.[54]

Quarrymen and working conditions

Inquest and probate records also play their role in revealing quarrying history. Those interested in labour history can also find plenty of material from inquests to uncover the industrial heritage and working conditions of those who worked with stone. John Collins died in July 1874 as a result of injuries received at the Malmsbury railway station. The 'dogs' being used to lift by crane a block of bluestone weighing nearly three tons, slipped and the falling stone crushed Collins who was standing underneath it.[55] Only a year earlier, in February 1873, quarryman Isaac Stephenson was killed near Malmsbury when working for the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company.[56] A group of men were working at the quarry on the property of the late James Pennington when the bolt at the top of the mast of the derrick crane came loose. The mast fell on Stephenson, knocking him against a large stone which killed him instantly. While this quarry was on private land, and the estate of Pennington was managed by trustees, no record of a registered quarry lease has been located.[57] In 1914, the trustees handed over the land to the Kyneton Hospital and contemporary newspaper reports show that quarrying continued on the land for some time. Thus there is further proof to be found of where specific quarrymen were working (witnesses to the inquest were John Fox and John Ashton) and that stone was being taken from Malmsbury for processing at Footscray. A similar accident happened in 1890 when William Rose was working in John Ryan’s quarry at Malmsbury.[58] While loading a stone onto a wagon for transport, Rose was working the windlass wheel when it slipped and the handle struck him on the skull, the resulting fracture being the cause of his death shortly afterwards. The information in the inquest file is too vague to determine the exact location of the quarry, but the Kyneton Guardian reported that it was 'about a mile and a half from the township on the road to Lauriston'.[59] This suggests the quarry was located on the currently-named Breakneck Road and would thus exclude it from being the 'Ryan’s Quarry' on Lidgey’s 1894 map.

The 1884 probate file of quarryman Richard Lightfoot of Kyneton exposes an intriguing story.[60] One of the assets listed is a 'one fourth interest in stone quarry at Malmsbury' valued at £30, but no title details are recorded. This implies the quarry was on private land not owned by the deceased, however no formal record of any lease has been found. The Kyneton newspapers from two years later reveal that Lightfoot, in conjunction with his brother Thomas, Malmsbury quarryman James Eastham and stonemason Peter Connell were quarrying on private land in 1884 under an unregistered lease.[61] The land was donated in the same year by the owner to the Salvation Army, the novelty of which meant the story was published in several regional and interstate newspapers, including a lampoon cartoon in the Bulletin.[62] The death of Richard Lightfoot that year meant the remaining three paid his widow his one-quarter share of the value of the work done in the quarry. Two years later in 1886, the quarrymen were taken firstly to the Malmsbury court, then the Supreme Court in Melbourne to have them evicted from the land.[63] The quarrymen believed they 'owned' the asset, being the workable quarry face, but with the court finding in the Salvation Army’s favour, the men, who had yet to harvest and sell any stone from the quarry face they had prepared, were forced to leave the property. Facing financial ruin, a community fund-raising scheme helped to meet some of their legal costs. It is perhaps ironic that Malmsbury bluestone was used in the base course of the very court which put them in this situation. Opening a quarry and preparing a workable face is a drawn-out process and requires much labour input before any profits can be made. These records highlight the risks taken by independent quarryman working on private land, without formal lease agreements.

Finding technical data

While the above explains the 'how' of tracing quarry history, providing technical information on the properties of specific stones is also a requirement for a GHSR nomination. Information on stones currently in use can be obtained by relevant suppliers, but stones that only have historical use present some difficulties. A very interesting and useful source is the 'Law Courts Stone Board' file located within VPRS 967/P0, Unit 41. This contains documentation relating to the Victorian Government board established in the 1870s to look into stone deemed suitable to use in the extensions to Parliament House and the new Supreme Court. Its contents include composition and physical test results for stones from sources such as the Grampians, Ceres, Tasmania, Kyneton, New Zealand and Portland (England).

Conclusion

Finding and recording holes in Victoria’s history is not as straightforward as it seems, in fact at times Beresford’s 'triangular' journey can seem one of going round in circles instead. There are today, however, numerous people who have an interest in knowing more about quarries and stones. These include the descendents of quarrymen and masons, those in direct contact with the products of their labour, through living or working in, or trying to preserve them, or those appreciating the parks and reserves created from repurposing the resulting quarry holes. The latter may be a means by which Victoria 'covers up its history with grass', but a decent dig in the archives can re-open these holes.[64] Some may even reveal additional stones suitable for a Global Heritage Stone Resource citation.

Acknowledgment

Aerial photography © The State of Victoria, Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, 2016. Reproduced by permission of the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning.

Disclaimer for aerial photography

This material may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or consequences which may arise from you relying on any information contained in this material

Endnotes

[1] Barry Ananian-Cooper, 'History', Global Heritage Stone, 31 August 2010, available at <http://www.globalheritagestone.org/home/history>, accessed 3 March 2016.

[2] Barry J Cooper, David F Branagan, Brenda Franklin & Helen Ray, 'Sydney sandstone: proposed Global Heritage Stone Resource from Australia', Episodes, vol. 38, no. 2, 2015, pp. 124–131.

[3] Barry Ananian-Cooper, 'GHSR Proposals', Global Heritage Stone, 31 August 2010, available at <http://www.globalheritagestone.org/home/ghsr-proposals>, accessed 3 March 2016.

[4] Alan H Spry, Building stone in Melbourne: a history of stone use in Melbourne particularly in the nineteenth century, Report for the Australian Heritage Commission and the Victorian Historic Buildings Council, Alan H Spry and Associates, 1988.

[5] Robert Irving, Ron Powell & Noel Irving, Sydney’s hard rock story: the cultural heritage of trachyte, Heritage Publications, Leura, NSW, 2014.

[6] MW Beresford, History on the ground: six studies in maps and landscapes, Lutterworth Press, London, 1957, p. 19, cited by Jo Guldi, 'Landscape and place', in Simon Gunn & Lucy Faire, Research methods for history, Edinburgh University Press, 2012, p. 69.

[7] Definitions of council and borough boundaries can be found in the Victoria Government Gazette.

[8] Malmsbury Historical Society, 'Summary of holdings, October 2011', available at <http://home.vicnet.net.au/~malmhist/ListofHoldings2011.pdf> and <http://home.vicnet.net.au/~malmhist/index_Page1025.htm>, accessed 3 March 2016.

[9] State Library Victoria, 'Victoria Government Gazette online archive 1836–1997', available at <http://gazette.slv.vic.gov.au/>, accessed 3 March 2016.

[10] Archive Digital Books Australasia, 'Home', available at <http://www.archivedigitalbooks.com.au/>, accessed 3 March 2016; see also Gould Genealogy and History, 'Victoria', available at <http://www.gould.com.au/Victoria-s/8.htm>, accessed 3 March 2016.

[11] Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources, 'Earth resources online store', available at http://earthresources.efirst.com.au/Default.asp?c=44353>, accessed 4 March 2016.

[12] E Lidgey, Report on the Malmsbury and Lauriston gold-field, Geological Survey of Victoria progress report, no. 8, Department of Mines, 1894, pp. 20–27.

[13] PROV, VPRS 16171/P0, Unit 1, Edgecombe Parish Plan, Imperial measure, 2576; Lauriston Parish Plans (1 to 4), Imperial measure 2979.

[14] Peter Cabena, Heather McRae & Elizabeth Bladin, The lands manual: a finding guide to Victorian lands records, 1836–1983, Royal Historical Society of Victoria, Melbourne, 1992, p. 68.

[15] PROV, VPRS 16685/P1, Unit 19, Bundle 124, Book 1459; Victoria Government Gazette, 18 February 1852, p. 175; PROV, VPRS 16171/P0, Unit 1, Malmsbury Township Plan, Imperial measure, 5495.

[16] 'Title deeds', Victoria Government Gazette, 27 April 1853, p. 596.

[17] Registrar General’s Office, Land memorial, Book 338, Memorial 349, dated 24 March 1887.

[18] PROV, VPRS 28/P0 Probate and Administration Files, Unit 107, Item 9/625, Richard Brodie of Bulla; VPRS 28/P2, Unit 6, Item 9/625, Richard Brodie of Bulla; VPRS 7591/P2 Wills, Unit 5, Item 9/625, Richard Brodie of Bulla; Australasian (Melbourne), 14 August 1875, p. 27.

[19] Registrar General’s Office, Transfer of Land Statute, AP File 9418 for Portions 25 and 34 Parish of Edgecombe, 28 August 1876.

[20] Shown by a search made of Victorian Birth Deaths and Marriages indexes.

[21] PROV, VPRS 28/P0, Unit 208 and VPRS 28/P2, Unit 81, both Item 17/968 probate of Joseph Shilton, gentleman of St Kilda, died intestate 18 May 1878.

[22] Malmsbury Borough Council Rate Books, photocopies held by Malmsbury Historical Society Inc., 1862–1872 and 1878–1894.

[23] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 348, Item 1876/998, inquest of Angus MacKay.

[24] 'Fatal Accident at Malmsbury', Kyneton Guardian, 22 November, 1876; 'Shocking death at Malmsbury', Kyneton Guardian, 25 November 1876; 'Shocking death at Malmsbury', Kyneton Guardian, 29 November 1876.

[25] R Brough Smyth, Mining and mineral statistics with notes on the rock formations of Victoria, Mason, Firth & McCutcheon, Melbourne, 1873, p. 36.

[26] Private Advertisements, Victoria Government Gazette, 13 October 1882, p. 2500; PROV, VPRS 932/P0, Unit 30, Item 482, Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company.

[27] Kyneton Guardian, 18 May 1887, p. 3; Kyneton Guardian, 21 May 1887, p. 2; Victorian Certificate of Title, vol. 927, folio 185259.

[28] PROV, VPRS 28/P0, Unit 907, Item 71/238, Alexander Hardie, deceased 6 March 1899; VPRS 28/P2, Unit 511, Item 71/238, Alexander Hardie, deceased 6 March 1899; VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 289, Item 71/238, Alexander Hardie, deceased 6 March 1899; Victorian Certificate of Title, Volume 927, Folio 185259; Malmsbury Borough Council, Letter Book, p. 493, letter dated 19 September 1902, photocopy held by Malmsbury Historical Society.

[29] Argus (Melbourne), 3 June 1899, p. 3.

[30] PROV, VPRS 28/P0, Unit 1209, Item 93/403, William Hall Fernie, deceased 6 December 1904; VPRS 28/P2, Unit 710, Item 93/403, William Hall Fernie, deceased 6 December 1904; VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 371, Item 93/403, William Hall Fernie, deceased 6 December 1904; Kyneton Guardian, 25 August 1904.

[31] There was a local quarryman David Davies but he, too, appears to have no links to the site.

[32] Vincent A Clark, Andrea Murphy, Sharon Lane & Jeremy Smith, Calder Highway Kyneton to Faraday archaeological and heritage study, vol. 2, Dr Vincent A Clark and Associates Pty Ltd, 1998, p. 123; Vincent A Clark & Andrea Murphy, Archaeological and heritage investigations in four proposed freeway corridors: Kyneton to Faraday, Interim Report on Stage 1 prepared for VicRoads, Dr Vincent A Clark and Associates Pty Ltd, 1998, pp. 15–16.

[33] PROV, VPRS 429/P0, Unit 1: Item 2123, p. 92; Item 2252, p. 101; Item 65, p. 109; Item 354, p. 127; Item 362, p. 128; Item 369, p. 129; Item 403, p. 130.

[34] 'The Coliban Viaduct', Mount Alexander Mail, 26 October 1859, p. 3.

[35] 'Serious railway accident at Malmsbury', Bendigo Advertiser, 14 December 1863, p. 2.

[36] PROV, VPRS 429/P0, Units 1 and 2. Based on a search of PROV Historic Plans Collection and index. PROV, VPRS 419/P0, Unit 9, Malmsbury and Kyneton were in contract number 7.

[37] George Ulrich, Quarter Sheet No. 9 N.W. Taradale geological map, second edition, revised, Geological Survey of Victoria, 1866.

[38] Land Victoria, Aerial Photography Register, Project 7723N7 559, Run 17, Film 1935, Image 89, August 1966; Project 7723N2 817/7, Run 10, Film 244, Image 27748, February 1946.

[39] PROV, VPRS 28/P2, Unit 816, Item 104/371 probate of Catherine McBride, died 13 June 1907; 'Sales of Crown lands in fee simple', Victoria Government Gazette, 23 September 1908, p. 4716.

[40] PROV, VPRS 28/P2, Unit 720, Item 94/428, probate of Patrick McBride, died 11 March 1905.

[41] 'Renewal of licences', Victoria Government Gazette, 4 January 1895, p. 28; 'Renewal of licences for year 1897 approved', Victoria Government Gazette, 26 February 1897, p. 84; 'Renewal of licences for the year 1901 approved', Victoria Government Gazette, 4 April 1901, p. 1222; 'Renewal of licences for the year 1904 approved', Victoria Government Gazette, 8 June 1904, p. 1707 (Victoria Government Gazette, Archive Digital Books version, using word search 'McBride').

[42] PROV, VPRS 7312/P1, 'Malmsbury' Grid C 06 file.

[43] PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5614, Item 2642/145; Malmsbury Borough Council Rate Books, 1862–1872 and 1878–1894, photocopies held by Malmsbury Historical Society.

[44] PROV, VPRS 226/P1, Unit 7, 1872–1873, p. 505; PROV VPRS 227/P0, Unit 27, 1873, Volume M, p. 551.

[45] PROV, VPRS 227/P0, Unit 28, 1874, Volume O; PROV VPRS 44/P0, Unit 418, Item 74/O 14381.

[46] PROV, VPRS 932/P0, Unit 20, Item 286; 'Malmsbury Stone Sawing Company', 'The Malmsbury Stone Sawing Company works', Bendigo Advertiser, 24 February 1874, p. 2.

[47] Malmsbury Borough Council Rate Books, 1862–1872 and 1878–1894, photocopies held by Malmsbury Historical Society.

[48] PROV, VPRS 44/P0, Unit 290, Item 71/D 10077.

[49] PROV, VPRS 16685/P0, Unit 19, Bundle 126, Book 970.

[50] Malmsbury Borough Council Rate Books, 1862–1872 and 1878–1894, photocopies held by Malmsbury Historical Society.

[51] PROV, VPRS 439, Unit 229, Item 2899/49.

[52] PROV, VPRS 419/P0, Unit 5, Volume 1, letter dated 25/6/1860.

[53] Victoria Government Gazette, 2 July 1867, p. 177; Victoria Government Gazette, 5 May 1868, p. 884.

[54] 'Municipal District of Brighton', Victoria Government Gazette, 9 September 1859, p. 1917.

[55] 'A terrible accident', Kyneton Guardian, 15 July 1874.

[56] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 286, Item 1873/119, inquest of Isaac Stephenson.

[57] PROV, VPRS 28/P0, Unit 110, Item 9/891, James Pennington; VPRS 28/P2, Unit 7, Item 9/891, James Pennington; VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 8, Item 9/891, James Pennington; 'Kyneton District Hospital', Kyneton Guardian, 15 August 1914, p. 2.

[58] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 566, Item 1890/892, inquest of William Rose.

[59] 'Malmsbury', Kyneton Guardian, 2 July 1890, p. 2.

[60] PROV VPRS 28/P2, Unit 172, Item 28/678 probate of Richard Lightfoot, died 16 October 1884.

[61] 'Malmsbury Police Court', Kyneton Guardian, 12 May 1886.

[62] Kyneton Observer, 29 July 1884; Victorian Certificate of Title, Volume 1473, Folio 294485; for example see 'A gift to the Salvation Army', Launceston Examiner, 8 August 1884, p. 2; Bulletin (Sydney), 9 August 1884, p. 12.

[63] PROV, VPRS 267/P0, Unit 748, Supreme Court, Barker versus James Eastham & Co.

[64] Geoff Chappel, Terrain: travels through a deep landscape, Random House, New Zealand, 2015, p. 120 (in reference to grassing over geology in road cuttings).

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples