Last updated:

'Rescuing the Regent Theatre', Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 4, 2005.

ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Louise Blake.

This article has been peer reviewed.

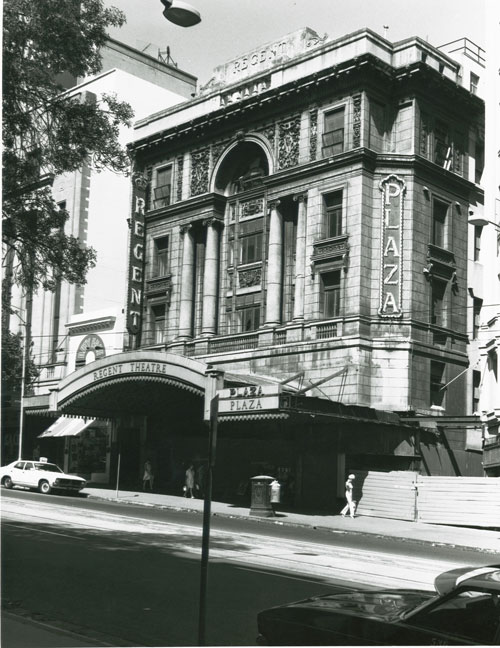

Melbourne’s Regent and Plaza theatres opened in Collins Street in 1929. For more than forty years, these grand picture palaces were among Melbourne’s most treasured cinemas, favourites together with the Capitol Theatre in Swanston Street and the State Theatre in Flinders Street. Often called ‘palaces of dreams’, they were part of a glamorous entertainment era, when a night out at the movies was an event, and an afternoon matinee was a treat. Not even the Regent’s two-year closure, as a result of the fire that destroyed the auditorium in 1945, could dampen the enthusiasm of its Melbourne audiences. By the 1960s, however, the grand picture palaces were no longer in vogue and were becoming uneconomical to run. The State Theatre closed in 1962 and was later converted into two theatres. The Capitol closed in 1964, but when it re-opened eighteen months later a shopping arcade had been built in the lower part of the auditorium. After investigating the option of converting the Regent into two theatres, its owner, Hoyts, opted to develop a smaller multi-cinema complex in Bourke Street instead. The company sold the Regent and Plaza theatres to the City of Melbourne in 1969 and in 1970 the doors of the Regent and Plaza closed for what many people thought was the last time.

Melbourne City Council bought the Regent and Plaza in order to control development around the site of the proposed City Square on the corner of Swanston and Collins Streets. The theatres seemed destined to fall victim to the wrecker’s ball. But if the 1960s was the decade of development, the 1970s was the decade of preservation. Protests against the demolition of historic buildings occurred around Australia, often with the controversial support of the building unions. The architectural profession debated the issues of preservation versus development of dynamic modern buildings. Both the State and Federal Governments were forced to introduce legislation to protect the nation’s built heritage. In Victoria the Liberal Government, under then Premier Rupert Hamer, introduced the Historic Buildings Act in 1974. The campaign to save the Regent and Plaza theatres was one of the battles of this preservation war.

Introduction[1]

When the Regent Theatre opened in Collins Street, Melbourne in 1929, the Australian Home Beautiful magazine published an article on the elaborate architectural features of the new picture palace. The author, known only as ‘Architect’, noted at the time that ‘a book might easily be written – and probably will be – describing this building in detail’.[2] While a book focusing on the Regent Theatre’s architecture is still to be written, the tumultuous history of the Regent – and its companion theatre, the Plaza – has been told more than once – in books (most notably in the book produced by Frank Van Straten and Elaine Marriner, The Regent Theatre: Melbourne’s palace of dreams,[3] in the press, in parliament, and at public meetings – over the last thirty-five years. ‘Architect’ could not have imagined in 1929 just what a complicated saga the story of the Regent and Plaza theatres would become. But just how did this saga evolve? Of all the former picture palaces and theatres in Melbourne, why, in the 1970s, did the threatened demolition of the Regent and Plaza cause such a public outcry? Were the theatres outstanding examples of the glamorous Hollywood era of entertainment, far too significant to Victoria’s heritage to be lost? Was it the renewed interest in preserving the State’s heritage that ultimately led to the theatres’ survival? Or was the theatres’ proximity to the City Square to blame for prolonging the saga – a saga worthy of the films the theatres once screened? Next year is the tenth anniversary of the re-opening of the Regent and Plaza theatres: what better time to consider these questions and explore what the building meant – and continues to mean – to the people of Melbourne?

A Gala Opening

The Regent was the flagship theatre of Francis W. Thring’s Hoyts chain. While Managing Director from 1924 to 1930, Thring (father of actor Frank Thring) opened a number of ‘Regents’ in Australia and New Zealand – the first in Sydney in March 1928. The Regent in Melbourne was the third in the chain, but by far the most elaborate. Designed by Cedric Ballantyne and built by James Porter & Sons, as many of Thring’s Regent theatres were, the Melbourne Regent with its Gothic grand foyer was said to resemble a cathedral.[4] The inspiration for the auditorium came from the Capitol Theatre in New York. ‘Architect’ described watching in wonder as the builders and artists put the finishing touches to the theatre – the stage curtain being sewn, the pictures being mounted, the elaborate chandelier waiting to be winched into place above the auditorium.[5] When it opened the Regent was the second-largest theatre in Australia with over 3000 seats. The opening on 15 March 1929 was a gala affair featuring an in-house orchestra conducted by Ernest G. Mitchell, Stanley Wallace at the console of the magnificent Wurlitzer organ, a ballet performance, and, finally, the screening of the silent film The two lovers starring Ronald Colman and Vilma Banky.[6] Thousands of people attended the event. The Plaza theatre, which opened two months later, was originally designed as a ballroom, but when a liquor licence was refused the plans were modified and the Plaza became a smaller theatre, with a distinctly Spanish atmosphere.

The 1920s heralded the beginning of the golden years of film-making – the Hollywood era. A theatre built during this time was often described as a ‘palace of dreams’.[7]Initially silent films were screened, but soon theatres were being converted to accommodate the ‘talkies’. The Plaza was the first new Australian cinema to open in the era of sound film. The opening on 10 May was another gala affair to match the style of the smaller, but luxurious cinema. While many of Melbourne’s theatres were in Bourke Street, the Regent and Plaza were located at the ‘Paris’ end of Collins Street. With the Town Hall, the Athenaeum and Georges’ department store located opposite, the Regent and Plaza became part of what Frank Van Straten has called ‘the Collins Street experience’.[8] Such was the interest in the escapist world of cinema that when fire destroyed the Regent’s auditorium in 1945, Hoyts obtained special permission from the State Government to enable the theatre to be reconstructed, despite wartime restrictions on building materials.[9] The reconstruction of the Regent, which included new plasterwork undertaken by James Lyall, would later become an issue in the debate concerning the architectural and historical merits of the theatre. In 1947 audiences were just grateful to see the theatre re-open. Their affection for the Regent and Plaza continued into the 1950s and 1960s, but television gradually changed the entertainment landscape.

PROV, VPRS 9963/P2, General Records, unit 1.

In 1969, when Hoyts sold the Regent and Plaza theatres to Melbourne City Council (MCC), there were many who felt that the golden years of the picture palaces were over. In the television age many of the larger theatres were becoming uneconomical to run. The State and Capitol theatres had both closed in the 1960s, and re-opened with reduced capacity. The State Theatre was converted into two smaller theatres, while the Capitol was reduced to one smaller theatre and a shopping arcade built in the area once occupied by the stalls. Hoyts briefly examined the possibility of converting the Regent into two smaller theatres, but opted instead to sell the Regent and Plaza and open a smaller multi-cinema complex in Bourke Street. MCC purchased the theatres for $2.25 million and subsequently called for tenders for development of the site. The Regent closed on 1 July 1970, followed by the Plaza on 4 November.

The City Square

Since the early 1960s Melbourne City Council had been considering the development of a city square. Councillor Bernard Evans first suggested the idea in 1961, but a formal proposal was not accepted until 1966. The Council then began acquiring property near the corner of Swanston and Collins Streets, including the Green’s building, Wentworth House, and the Cathedral Hotel. When developers expressed an interest in the Regent Theatre site, MCC decided to purchase it in order to control development around the future City Square. Before the theatres had even closed, the Council accepted the tender of British development company Star (Great Britain) Holdings Ltd, who planned to build an international hotel overlooking the Square. Newspaper articles published at the time depict a 53-storey rectilinear building towering over the Town Hall and St Paul’s Cathedral. The 445-bed hotel would occupy 24 storeys, with the remaining floors to be used as office space. The money MCC would receive from Star would assist in its funding of the City Square project.[10] Looking at the structure as depicted in the newspapers, it is not surprising that some people were outraged by the proposal.[11] But despite this opposition the public campaign to save the theatres did not begin in earnest until 1973, after MCC’s deal with Star Holdings had failed. Star blamed the Federal Government’s new foreign investment laws on its failure to raise the necessary capital, while the Council announced it would ‘make a clean break and, freed of the restraints it suffered in the past, embark on a new concept’.[12]

MCC’s decision to purchase the Regent and Plaza theatres as part of the City Square project was one of the factors that, ironically, ensured the theatres’ survival. The Council’s plans for the City Square were dependent on the redevelopment of the Regent site; while the future of the Regent remained unresolved the Council was unable to move forward with the City Square. Community groups seized on the opportunity presented by the Council’s ‘clean break’ and the campaign to save the Regent and Plaza theatres began.

The Decade of Preservation

The campaign to save the theatres could not have come at a better time in the history of the preservation movement. The 1970s were characterised by a renewed interest in historic buildings, not only by members of the wider community but also by some in the State and Federal Governments. Membership of the National Trust had expanded to include younger professionals, and some residents groups had formed in an effort to protect their streets and suburbs from what they perceived to be unnecessary development. In an effort to encourage the preservation of the nation’s built heritage, the Victorian branch of the National Trust had drafted a heritage bill in 1969 and presented it to the State Government. When the Government failed to act on this bill, the Trust put pressure on the State opposition. In 1972 Rupert Hamer became Premier and Minister of the Arts, and by the end of 1973 an amendment to the Town and Country Planning Act, known as the Historic Buildings Bill, was introduced into State Parliament and passed in May 1974. In an article on the development of heritage legislation, Sheryl Yelland has argued that this Victorian legislation was far from perfect.[13] But it was important as the first of a series of acts passed in State and Federal parliament aimed at protecting sites of architectural significance. On a Federal level, Prime Minister Whitlam, whose Labor Party had come to office in 1972, announced the formation of a Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate. Submissions were received from individuals and groups around the country and the subsequent report recommended greater government involvement – to match the interest of the community – in issues of preservation.[14]

In Melbourne, 1973 was a tumultuous year in the preservation wars. When the Commercial Bank of Australia (CBA) announced that it intended to redevelop its building in Collins Street – which included an historic banking chamber dating back to the 1890s – the National Trust mounted a public campaign to prevent its demolition, beginning with the listing of the chamber on its register of historic buildings. The Trust encouraged supporters to sign petitions objecting to the proposal, and in a three-week period had gathered the support of more than 150,000 people.[15] The Australian Building Construction Employees & Builders Labourers Federation, under the leadership of Norm Gallagher, lent its support to the campaign by placing a black ban on any demolition of the building. As a result of the Trust’s campaign, Premier Hamer announced a Committee of Inquiry in October 1973 to investigate the feasibility of retaining the banking chamber. To the relief of the Trust’s supporters, the inquiry recommended that the banking chamber remain.[16]

While the National Trust took a proactive approach to the preservation of the CBA banking chamber, it was less vigorous in its response to the fate of the Regent and Plaza theatres. As Graeme Davison writes, the Trust ‘vacillated on the issue’ by adding, removing and then reinstating the theatres on its register of twentieth-century buildings. Davison argues that the Trust ‘struggled to reconcile its belated support for the Regent with its traditional adherence to canons of “good taste”‘.[17] It was not the Trust who fronted the campaign, he writes, but,

a wider coalition of trade unionists, especially theatrical and building industry employees, show business celebrities and interested members of the public.[18]

PROV, VPRS 9963/P2, General Records, unit 1.

The Save the Regent Theatre Committee was the key group within this coalition, having formed in the early years after the closure of the Plaza and Regent in 1970. The group comprised former employees of the theatres and members of the Theatre Organ Society of Australia (TOSA), including industrial designer Robert Laidlaw and Ian Williams. Williams, like Laidlaw a member of TOSA, began his career at the Regent Theatre in May 1949 and later became Assistant Manager of the theatre. Although not part of the initial group, Loris Webster was the only woman on the Committee and soon became its public face. Webster, who together with her husband ran the Wild Cherry restaurant a few doors up from the Regent, was prompted by the public response to the closure of the theatres and offered her assistance to the Committee. People would often comment to her, she said, that they had never been asked for their views about the Regent. The public didn’t want to see it go. Webster believed the only way the theatres could be saved was as the result of a political decision.[19] To this end, she enlisted the support of Norm Gallagher. At one of the Committee’s audio-visual nights, which was organised to gather support for the campaign, Gallagher agreed to put a black ban on the demolition of the Regent and Plaza, commenting that he had once worked at the Regent as a ‘lolly boy’.[20] Union bans also extended to other buildings on the site, including Wentworth House.

The building unions played a prominent role in the preservation battles of the 1970s. In Sydney, the Builders Labourers Federation, under the leadership of Jack Mundey, had instigated a ‘green ban’ campaign. In a history of this movement, Meredith Burgmann states that the union’s guiding principle was ‘that workers had a right to insist that their labour not be used in harmful ways’.[21] In 1972 the union became involved in a campaign to save two of Sydney’s theatres – Francis W. Thring’s Regent, then owned by JC Williamson Ltd, and the Theatre Royal. The Save the Regent Theatre Committee and the Save the Theatre Royal Committee joined forces from 6 November 1972 to form a group known as Save Sydney’s Theatres Committee. The campaign to save the Sydney Regent was initially successful, but by the 1990s the theatre had fallen victim to development and was demolished.[22]

Press reports regarding the fate of the Melbourne Regent criticised the involvement of the union. The editor of the Melbourne Herald argued that,

Mr Gallagher seems less concerned with the fate of the Regent than with a power play. There is no room in our society for such strong-arm tactics.[23]

The Regent was not the only site affected by a union black ban. A booklet announcing a ‘green ban’ gallery at Trades Hall lists numerous buildings in Melbourne, including Tasma Terrace, the Windsor Hotel, the Princess Theatre, and the City Baths.[24] During a Committee of Inquiry in 1975 the MCC questioned Gallagher’s motives for getting involved in the campaign, claiming that the union had placed the ban on the Regent because the Council had closed a swimming pool in Batman Avenue.[25] The union booklet doesn’t dispute the connection. Whatever the union’s motives, it can be argued that the black ban Gallagher placed on the Regent’s demolition, together with the efforts of the Save the Regent Theatre Committee, were responsible for the theatre’s initial survival. Without them, demolition may well have gone ahead and the battle would have been lost before it even began.

In August 1973 the Save the Regent Theatre Committee received unexpected support from Premier Rupert Hamer. According to Frank Van Straten, Hamer had commented that he wished to see the Regent preserved, ‘recalling fondly that it was at the Regent that he and his wife had courted’.[26] Supporters, including Committee members Laidlaw and Williams, immediately began writing to the Premier thanking him for his comments and urging him to resolve the issue.[27] At the time that Hamer made these remarks, discussions were taking place between MCC and the State Government over the location of the proposed concert hall for the Arts Centre. The Council-owned site at Snowden Gardens was favoured, but, as Vicki Fairfax notes, difficulties with the Council prompted Hamer’s suggestion that the Regent Theatre be converted into a concert hall instead.[28]

In October 1973 the Secretary of the Premier’s Department, KD Green, wrote to George Fairfax, Executive Officer of the Victorian Arts Centre Building Committee, requesting that the Committee prepare a report on the concert hall proposal for the Premier. Green stated that

it has been pointed out to the Premier that the Regent Theatre is in a bad state of repair and that considerable work would be necessary to restore it to its former condition, quite apart from the effect on the City Square project of leaving the Theatre where it is.[29]

Green commented that the Premier ‘would be prepared to reconsider his views if an appropriate report could be prepared’ regarding the two sites. After receiving reports from architect Sir Roy Grounds and other consultants, the Building Committee recommended in favour of the Snowden Gardens site. The Council finally gave its approval for the use of Snowden Gardens and the Premier formally announced the location of the new concert hall.[30]

With the concert hall proposal no longer an option, debate surrounding the future of the Regent Theatre waged on. Throughout 1974 the Save the Regent Theatre Committee continued its campaign, gathering letters of support from performers such as Sir Robert Helpmann and Gladys Moncrieff. In a letter to the Committee, Helpmann commented on the lack of theatrical venues in Australia, stating that

it is terribly sad that with a beautiful Theatre like the Regent that anyone should even have thought of demolishing it and I think that everything that possibly can be done should be done to save this for the future of the Australian Theatre.[31]

Another patron of the Committee, Dame Joan Hammond, also referred in her letter to the lack of theatres in Melbourne, arguing that it ‘is a sad indictment on its people’.[32] Melbourne City Councillor David Jones, who had previously managed the Regent Theatre, was also a voice of support for the Committee, despite his position on Council. In March 1974 the Committee presented Gough Whitlam with a submission to the Federal Government’s Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate during his visit to Doncaster City Hall. Although the submission was too late to be considered for the Inquiry, the Prime Minister commented that the Committee had a ‘good case’ for saving the theatre and referred the matter to the Minister for Urban and Regional Development, Tom Uren.[33] Uren had previously expressed his support for the campaign to save the theatres.[34]

The Committee’s determined campaign, led by Loris Webster, was a source of frustration for MCC, which had commissioned a number of reports into the City Square development. New Lord Mayor, Councillor Ron Walker, had made it his mission to resolve the issue and shared the desire of his predecessors to demolish the theatres. Architectural firm Clarke Gazzard Pty Ltd had undertaken a feasibility study into the City Square development, which it presented to the Council in August 1974. The report suggested three alternative developments for the City Square, one of which included the retention of the Regent Theatre. The report stated that the theatre was,

suitable for a wide range of theatrical activities and [had] a definite role to play in Melbourne’s theatrical life.[35]

In response to the recommendation that the theatre be preserved, the Council commissioned a report from chartered accountants Fell and Starkey into Clarke Gazzard’s proposal. The accountants concluded that the architectural firm’s costings were not sound. Despite MCC’s reluctance to consider Clarke Gazzard’s controversial third alternative development, the report was a boost to the Save the Regent Theatre Committee and would prove to be helpful during the forthcoming Committee of Inquiry.

In late 1974 Lord Mayor Walker wrote to the Premier requesting that he appoint a Committee of Inquiry to resolve the Regent Theatre issue, as the Premier had done the previous year with the CBA banking chamber inquiry. Walker’s letter reveals his frustration over the issue, writing ‘all I am trying to do is get on with the job’.[36] The letter also alludes to the Council’s views on the Regent’s supporters, stating that the ‘most responsible parties in this dispute are the National Trust and my Council’. The union had lifted its black ban on the demolition of Regency House and Wentworth House, but its ban remained on the Regent Theatre.

The National Trust meanwhile had reinstated the Regent Theatre on its register of twentieth-century buildings in August 1974. In its October newsletter, the Trust argued that the Regent Theatre had been removed from, and then restored to the register because of concerns regarding its condition, not because of its importance, or lack thereof. The newsletter article defended criticism of the Trust,

for not being more active in the evaluation of 20th century buildings but it is determined only to register a building after the most detailed evaluation by experts.[37]

The Trust’s belated support for the retention of the theatres, while welcomed by the Save the Regent Theatre Committee, was not of overwhelming concern to the Council. Unlike the Trust’s public battle over the CBA banking chamber, which forced the Premier to appoint a Committee of Inquiry, the union ban and the campaign by the Save the Regent Theatre Committee were largely responsible for forcing MCC to request a Committee of Inquiry to resolve the issue.

Committee of Inquiry

The Premier announced the formation of a Committee of Inquiry into the Regent Theatre in February 1975. Louis F Pyke, Chairman of Directors of Costain Australia Ltd, acted as Chair. Pyke was accompanied by architect Ronald G Lyon, theatrical producer Harry M Miller, and consulting engineer R Milton Johnson, who had served on the committee of the CBA banking chamber inquiry. FT Cron, from the Premier’s Department, was appointed Secretary. Records in the inquiry files reveal that discussions had taken place between Louis Pyke and Norm Gallagher about the possibility of Gallagher appearing on the Committee. Cron considered this to be a ‘dangerous move’, and suggested that Gallagher be approached to provide a written submission instead.[38] There is no evidence on file to suggest that Gallagher or the union did so; nor did Gallagher appear at the public hearings, despite being invited.

Running concurrently with the Committee of Inquiry, the newly formed Historic Buildings Preservation Council (HBPC) was considering a submission by the Save the Regent Theatre Committee to include the Regent and Plaza theatres on the register of historic buildings. Many of the organisations that made submissions to the Committee of Inquiry also provided information to this Council. The HBPC investigation had a narrower focus than the Premier’s inquiry, determining if the building,

had such historical or architectural importance that its addition to the Register of historic buildings could be recommended.[39]

The terms of reference for the Committee of Inquiry firmly linked the future of the Regent Theatre to the City Square project. The Committee was directed to investigate,

the desirability and technical and economic feasibility of retaining the Regent Theatre as part of the future City Square project, having regard to its present condition and any architectural or historic merit it may possess.[40]

Shortly after the Inquiry was announced, advertisements appeared in the press calling for written submissions. The Committee approached various individuals and organisations for advice, and also inspected the theatres on a number of occasions. In addition to these submissions, a public hearing was held over three days in July with a number of witnesses called, including members of the Save the Regent Theatre Committee, MCC’s Town Clerk, representatives of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, and several individuals involved in the arts and venue management. The files of the Inquiry, which include a transcript of the three-day hearing, reveal that the issue had become a battle between the community, which wanted to see the theatres used, and the Council and many in the architectural profession who were pushing for the City Square, believing that the Regent and Plaza theatres were impediments to a successful development.

PROV, VPRS 9963/P2, General Records, unit 1.

Unsolicited letters in the inquiry files indicate consistent support for the Regent’s survival from members of the general public who remembered attending the theatre in its heyday. One correspondent recalled ‘the terrific orchestra and pianos of Isador Goodman’.[41] Another suggested that the theatre ‘should be reopened for the showing of old beautiful and timeless classics’.[42] And surprisingly, two letters were received from a thirteen-year-old boy from Niddrie who composed a poem in support of the Regent.[43] But some members of the public were not in favour of saving the grand old picture palace. A correspondent from Emerald suggested the theatre,

is not in anyway noteworthy as an architectural masterpiece, being simply and solely an ordinary picture theatre similar to many more in the city and suburbs […] there is far too much mere sentiment about both conservation and the presvervation [sic] of buildings.[44]

One wonders, given the description of the Regent as ‘an ordinary picture theatre’, if this correspondent had ever been inside the theatre! Many of its supporters would have argued that there was nothing remotely ‘ordinary’ about the Regent.

As this last letter indicates though, the architectural style of the Regent and Plaza theatres was not highly regarded by everyone, particularly those in the architectural profession. In 1975 a letter from a group of architects appeared in the newspapers, claiming that the ‘important matter’ of the Civic Square,

is perhaps not understood by those who feel the Regent Theatre, which would limit this development, should be preserved if only for sentimental reasons, because there can be little architectural and obviously no economical reasons.[45]

The architects argued that the theatres had served their purpose as cinemas and were not suitable as live venues.

While some progress had been made in changing society’s attitudes towards the preservation of historic buildings, there was still a strong bias in favour of nineteenth-century buildings. The glittering architecture and plaster ornamentation of a twentieth-century picture palace were not considered worth saving. It would also take some time before the social or cultural significance of a building made it worthy of preservation. This attitude was reflected in the Council’s evidence to the Inquiry. Town Clerk, FH Rogan argued that,

we submit that there was nothing innovatory about the Regent Theatre, that externally it is not attractive. There were no aesthetic values, in fact it could be generally agreed that the bulk of that building is ugly when viewed from the outside. It was built by commercial people, for commercial reasons, to maximise their return.[46]

MCC argued that ‘in their present form both buildings are little more than shells’.[47]

This description was adamantly contested throughout the Save the Regent Theatre Committee’s campaign, which was supported by the National Trust’s submission. The Committee argued that the Regent was structurally sound, had excellent stage facilities, large seating capacity, first class acoustics, and was in an ideal location in the city, and declared the theatre,

one of the finest – if not the finest – examples of the great picture palaces. [It] represent[s] an era in the lifestyle and entertainment of the people of this State.[48]

Both the Committee and the National Trust referred to the recent trend of converting old picture palaces in the United States and commented that the same could be done with the Regent.[49] In her closing address Loris Webster even suggested that a Board of Commission comprising the Council and the State Government be established to retain ownership and management of the theatres.[50] Ironically, the arrangement Webster suggested is similar to the deal negotiated in the 1990s that finally enabled the Regent to reopen in 1996.

The public hearings concluded on 11 July. At a meeting with the Premier that afternoon, the Committee advised Rupert Hamer that it ‘was of the opinion that the Regent and Plaza should be retained despite the likely cost of approximately $6M for restoration’. The Premier acknowledged that ‘he would not like the Regent to be demolished if there were appropriate uses for the building’.[51] In the Committee’s report it argued that,

the problem cannot be reduced to one of tear down or leave, cost or profit. The simple fact is that the combination of the buildings are, in our opinion, a RESOURCE which is indeed a valuable one not only to the City of Melbourne, but to the State as a whole.[52]

Just as Clarke Gazzard had proposed in its feasibility study the year before, the Committee recommended that ‘the Regent Theatre complex should be retained and integrated in the design of the City Square’.

The results of this inquiry reveal that the Regent and Plaza theatres were spared from demolition not necessarily because of any significant architectural or historic merit, however justified, but, as the Save the Regent Theatre Committee cleverly argued, because the theatres were a resource for the community. The HBPC investigation, with its limited scope, found that the theatres had some architectural or historical merit, but not enough to warrant inclusion on its register of historic buildings.

Thirty years on from the inquiry, Loris Webster recalls feeling emotional giving her concluding address on the last day. It had been a tough battle at times, fighting to get their message across against the well-resourced Council. Not only had she been personally attacked, but her children had also been harassed because of their mother’s stand. But the fight was worth it, she says. It was the perfect example of a community working together.[53]

PROV, VPRS 9963/P2, General Records, unit 1.

The successful outcome of this inquiry was, indeed, an example of the community working together. The Regent and Plaza theatres would not have survived this long had it not been for the efforts of the Save the Regent Theatre Committee and its supporters. But despite the recommendation that the Regent and Plaza be retained, the theatres would remain empty for the next twenty years.

Plans and Proposals

In the years immediately following the inquiry, criticism of the decision to save the theatres continued to appear in the press, and union bans on the site remained.[54] It wasn’t until 1980 that the City Square, designed by the competition winners Denton Corker Marshall, finally opened. The Plaza was absorbed into the City Square project, with the interior of the theatre replaced with shops, bars and restaurants. Members of the Save the Regent Theatre Committee continued to keep a close watch on these developments.

Throughout the 1980s numerous suggestions and proposals were made for the development of the theatres. The Ministry for the Arts paid close attention and its files reveal the continuing developments in the Regent Theatre saga. In 1985 other community groups emerged, such as the Regent Arts Alliance, which put forward a proposal for the Regent to become a community arts complex that could include rehearsal venues, events and exhibitions, children’s activities, retail space, and office space for arts organisations.[55] Keith Scoble submitted a proposal to Council suggesting that the Regent could be developed as a live theatre, with offices, restaurant, a tavern, retail and public space. Michael Edgley Holdings Ltd would manage the live theatre component.[56] There was even a suggestion from the ‘Unemployed Musicians Union’ suggesting that the theatre could become a venue for ‘underexposed and unemployed bands, sound technicians, and lighting technicians’.[57] In 1987 the Chase Corporation won the tender for redevelopment of the site, planning to refurbish the Regent and ‘make it the major theatre of Melbourne and a complex of international renown’.[58] But like so many proposals for the site, this too faltered.

Amidst these discussions were other developments in the live theatre industry in Melbourne, which foreshadowed a final resolution of the Regent Theatre saga. In 1986 Her Majesty’s Theatre was listed on the Victorian Heritage Register, after threats of demolition and protests by the unions and theatre community.[59] The author of the report for the Historic Buildings Council commented that the opening of the Arts Centre in 1984 had complicated the use of existing theatres. Although the Arts Centre provided additional venues, they were State Government-run and had shifted ‘resources and influence from the private to the public sector in the live entertainment industry’.[60] Despite this, the author argued that Her Majesty’s Theatre was still a viable option as a live theatre venue. Following the theatre’s successful listing, Her Majesty’s was refitted to accommodate the production of Cats. Two years later the Regent Theatre was finally recognised as a significant heritage building and was listed on the Victorian Heritage Register. The statement of significance makes for interesting reading. Despite the arguments in the 1970s, the Regent was considered to have architectural significance,

as one of the best surviving examples of an inter-war period picture palace in Australia [with an] imaginative combination of styles and sumptuous and spectacular interior spaces.[61]

The building had historical significance for its part in the development of cinema in Victoria, and for its association with Francis W Thring. But of particular interest to this story is the Regent’s social significance as ‘the subject of Melbourne’s longest running conservation debate’.[62]

The story of the Regent’s survival had a happy ending in 1996, when the former picture palace re-opened as a live theatre. After purchasing and refurbishing the Princess Theatre in 1987, Marriner Theatres negotiated a deal with the State Government, MCC and the building unions that resulted in the refurbishment and re-opening of the Regent. The project was expected to cost $25 million. The Plaza theatre, which had been gutted by the City Square development, re-opened as a licensed ballroom, reflecting Thring’s original plans. Allom Lovell and Associates undertook the multi-million dollar restoration and Marriner Theatres took over the lease of the building. The opening night on 17 August 1996 was an emotional event for many, particularly those members present from the Save the Regent Theatre Committee. Ian Williams called it ‘the happiest night of my life’.[63]

Conclusion

Graeme Davison has argued that the Regent Theatre survived,

not because the experts said the building was important, but because the trade unions, and many members of the public, cherished the fake opulence and celluloid illusions of an old-time picture palace more than the magnificent emptiness of a City Square.[64]

It’s a fair assessment of the saga. The Save the Regent Theatre Committee was instrumental in gathering community support and forcing the Council to request a Committee of Inquiry. Committee member Loris Webster credits Norm Gallagher with saving the theatre,[65] but others would argue that it was Webster and the Committee who had the far greater impact. The Regent Theatre saga is a lesson in the history of the preservation wars of the 1970s and the power of community support. But more than that, the longevity of the debate allowed attitudes and circumstances to change so that the Regent’s significance could be recognised and its viability as a live theatre embraced. In the nine years since its re-opening, audiences have been treated to musicals such as Sunset Boulevard, Man of La Mancha, We will rock you and, now, The lion king, as well as live music from performers such as Brian Wilson, KD Lang and Jackson Browne. Although some of the buildings around them may have changed since 1929, the Regent and Plaza theatres remain an important part of the Collins Street landscape.

Endnotes

[1] Thanks are extended to Frank Van Straten, who was a valuable source of information and contacts and who kindly provided feedback on my initial draft. The book he and Elaine Marriner produced, The Regent Theatre: Melbourne’s palace of dreams, is an excellent source on the entire history of the theatre. Thanks to Elaine Marriner who gave me access to some of the Regent Theatre archives. And finally, thanks to Loris Webster and Ian Williams who kindly shared with me their stories of the Save the Regent Theatre campaign.

[2] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Save the Regent Theatre Committee submission, ‘Architect’, ‘The building of the Regent Theatre’, clipping from Australian Home Beautiful, 1 April 1929, p. 63.

[3] F Van Straten, The Regent Theatre: Melbourne’s palace of dreams, ELM Publishing, Melbourne, 1996.

[4] ‘Architect’, p. 68.

[5] ibid., p. 63.

[6] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Save the Regent Theatre Committee submission, Regent Theatre Gala Opening inaugural programme, 15 March 1929.

[7] S Brand, Picture palaces and flea-pits: eighty years of Australians at the pictures, Dreamweaver Books, Sydney, 1983, p. 78.

[8] Frank Van Straten, interview, 13 April 2005.

[9] Van Straten, The Regent Theatre, p. 43.

[10] PROV, VPRS 9444/P1, Unit 1, 1969-70, ‘$40 million tower goes up in 1971’, unsourced newspaper clipping.

[11] PROV, VPRS 9444/P1, Unit 1, 1969-70, ‘Save our City Square’ flyer.

[12] PROV, VPRS 9444/P1, Unit 1, 1973-74, Melbourne City Council press release, 21 June 1975.

[13] S Yelland, ‘Heritage legislation in perspective’, in G Davison & C McConville (eds), A heritage handbook, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1991, p. 45.

[14] Commonwealth Government of Australia, Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1984, pp. 28-9.

[15] National Trust of Australia (Victoria), In Trust: the first forty years of the National Trust in Victoria 1956-1996, National Trust, Melbourne, 1996, p. 46.

[16] Report of the Committee of Inquiry into feasibility of preserving the Banking Chamber, Commercial Bank of Australia Ltd, Collins St, Melbourne, 1974.

[17] G Davison, ‘The battle for Collins Street’, in A heritage handbook, pp. 122-3.

[18] ibid.

[19] Loris Webster, interview, 27 April 2005.

[20] ibid.

[21] M & V Burgmann, Green bans, red union, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998, p. 3.

[22] ibid., pp. 238-40.

[23] PROV, VPRS 12827/P4, Unit 10, 55/20/16, ‘Overacting at the Regent’, clipping from Herald (Melbourne), 17 November 1974.

[24] Australian Building Construction Employees & Builders Labourers Federation, Builders’ laborers defend the people’s heritage, Melbourne, 1975 (Regent Theatre archives).

[25] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, FH Rogan, Transcript of evidence to Committee of Inquiry, 11 July 1975, p. 229.

[26] Van Straten, The Regent Theatre, p. 66.

[27] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 177, 1750/13/1, Ian Williams to Premier Rupert Hamer, 18 August 1973.

[28] V Fairfax, A place across the river: they aspired to create the Victorian Arts Centre, Macmillan Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2002, p. 120.

[29] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 177, 1750/13/1, KD Green to George Fairfax, 9 October 1973.

[30] Fairfax, ibid.

[31] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Save the Regent Theatre Committee submission, Sir Robert Helpmann to TR Laidlaw, 8 July 1974.

[32] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Save the Regent Theatre Committee submission, Dame Joan Hammond to TR Laidlaw, 5 August 1974.

[33] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 177, 1750/13/1, ‘Gough may save the Regent’, clipping from Sunday Press, 10 March 1974.

[34] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Save the Regent Theatre Committee submission, Brian McKinlay, ‘Fighting for an amazing pleasure dome’, clipping from Nation Review, 8 March 1974.

[35] PROV, VPRS 12827/P1, Unit 143, 0/29-02-08-1, Clarke Gazzard Pty Ltd, Melbourne civic square feasibility study, August 1974.

[36] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 177, 1750/13/3, Lord Mayor Ron Walker to Premier Rupert Hamer, 2 December 1974.

[37] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Save the Regent Theatre Committee submission, ‘Theatre splendour must be preserved’, clipping from Trust Newsletter, October 1974, pp. 8-10.

[38] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 177, 1750/13/3, FT Cron, ‘Regent Theatre’, 19 February 1975.

[39] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Historic Buildings Preservation Council, Report to the Minister for Planning, the Honourable A. J. Hunt, M.L.C on the application by the Save the Regent Theatre Committee for the Regent and Plaza Theatres Collins Street, Melbourne to be added to the register of historic buildings, August 1975, p. 5.

[40] PROV, VPRS 12827/P4, Unit 10, 55/20/16, public advertisement, clipping from Herald, 8 March 1975.

[41] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 178, 1750/13/7, Mrs Del Pascoe to FT Cron, 9 March 1975.

[42] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 178, 1750/13/7, Mr CEL Horton to FT Cron, undated.

[43] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 178, 1750/13/7, Paul McCluskey, 11 July 1975.

[44] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 178, 1750/13/7, Rev. JE Hull to FT Cron, 8 February 1975.

[45] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Melbourne City Council submission, John D Fisher to the Editor, clipping from Herald and Weekly Times, 10 April 1975.

[46] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, FH Rogan, Transcript of evidence to Committee of Inquiry, 9 July 1975.

[47] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Melbourne City Council submission, p. 3.

[48] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Loris Webster, Transcript of evidence to Committee of Inquiry, 9 July 1975.

[49] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, National Trust of Australia (Victoria) submission.

[50] PROV, VPRS 9963/P1, Unit 1, Loris Webster, Transcript of evidence to Committee of Inquiry, 11 July 1975.

[51] PROV, VPRS 7614/P1, Unit 178, 1750/13/9, ‘Meeting with Premier’, 11 July 1975.

[52] Regent Theatre: Report of Committee of Inquiry into feasibility of retaining the Regent Theatre in Collins Street as an integral part of the future City Square project, [1975], Government Printer, Melbourne, 1976, pp. 47-8.

[53] Webster, interview, 22 April 2005.

[54] PROV, VPRS 12827/P4, Unit 10, 55/20/16, ‘Pull it down’, clipping from Herald, 12 March 1976.

[55] PROV, VPRS 12827/P4, Unit 10, 55/20/16, Regent Arts Alliance, ‘Preliminary ideas for discussion’, 14 May 1986.

[56] PROV, VPRS 12827/P4, Unit 10, 55/20/16, KW Scoble, 12 June 1986.

[57] PROV, VPRS 12827/P4, Unit 10, 55/20/16, David Bailey to the Ministry for the Arts, July 1985.

[58] Melbourne City Council & Chase Corporation Australia, The Regent City Square Development: a new beginning, promotional brochure, courtesy of Ian Williams.

[59] Her Majesty’s Theatre, ‘History’, available at http://www.hermajestystheatre.com.au/theatre.html, accessed 20 August 2004, .

[60] M Colligan, Her Majesty’s Theatre 1886-1986: a report prepared for the Historic Buildings Council, Historic Buildings Council, Melbourne, 1986, p. 31.

[61] Heritage Victoria, ‘Heritage Register Online: Regent Theatre’, viewed 23 September 2004, http://www.heritage.vic.gov.au.

[62] ibid.

[63] Ian Williams, email, 16 April 2005.

[64] Davison, p. 122.

[65] Webster, interview, 22 April 2005.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples