Last updated:

‘The notorious Michael O'Grady: Big Mick in early Melbourne’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 16, 2018. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Lauren Murphy.

Michael ‘Big Mick’ O’Grady was a notorious character in Melbourne’s early days. He was both a criminal and a constable, and at one point considered entering politics. His misdemeanours were celebrated in the newspapers of the day; however, since his death, his story has been lost to history. I intend to resurrect this figure so that modern audiences can appreciate the combination of criminality and larrikinism that helped to build the character of our city and nation.

On 11 March 1847, the Port Phillip Patriot reported that Michael O’Grady was arrested for stealing a blunderbuss—a firearm with a fluted muzzle. The article stated that ‘some fun may be anticipated’ at the hearing, due to ‘Mr Grady’s well-known oratorical powers’.[1] This is one of many lighthearted, humorous stories about ‘Big Mick’ that appeared in the Melbourne press during the 1840s. Each story adds to an evolving picture of a man who gained fame, or infamy, for being both a criminal and an enforcer of the law.

O’Grady’s exploits made him well known in Melbourne during his lifetime; however, he has been overlooked in histories relating to the establishment of the City of Melbourne. Most histories of early Melbourne focus on more renowned and respectable characters—people who have streets and suburbs named after them. By contrast, Big Mick was a beloved nuisance and source of entertainment for the people of the city. Victorian Public Records Series (VPRS) 19—which primarily consists of correspondence directed to the superintendent of the Port Phillip District—contains a number of letters from O’Grady. Were it not for these letters at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), the historical record of Big Mick would be limited to sensationalist newspaper accounts. By neglecting O’Grady’s story, we have overlooked a figure who, arguably, influenced early Melbourne’s character and (along with many other similarly overlooked local figures) contributed to the emerging national character.

Michael O’Grady, sometimes referred to as Michael Grady, but more commonly known as Big Mick, was transported to Australia in 1832.[2] A repeated absconder, his physical appearance was described in the New South Wales Government Gazette on numerous occasions during the 1830s. He was 5 foot 10½ inches (179 centimetres) tall, with a ruddy, freckled complexion, light brown hair, light grey eyes, a scar over his left eyebrow and another scar on his left arm.[3] O’Grady’s height, hardly deserving of the moniker ‘big’ in modern times, was nonetheless quite tall by convict standards; most of the other runaway convicts in the Gazette were listed as being around 5 foot 4 inches tall. A letter written by O’Grady in the 1840s reveals that he was rejected from service in the border police due to his size;[4] however, it is not clear whether this was because he was too tall or too heavy or both. Certainly, his employment as a night watchman conjures the possibility that he may have been an intimidating figure.

Despite his repeated escape attempts, O’Grady received his ticket of leave in 1839.[5] His first appearance in Melbourne’s newspapers hardly belies his later notoriety; he was listed among many who were fined 5 shillings in June 1840 for the crime of drunkenness—convicted ‘for the first time!’, the Port Phillip Patriot proclaimed with characteristic jocularity and enthusiasm.[6]

Drunkenness was a problem in the colony. Robyn Annear, author of Bearbrass, describes drunkenness as the ‘common ingredient in most of the crimes and misdemeanours to attract the notice of the police and newspapers’.[7] O’Grady’s later appearances before the court, as described in newspaper reports, often mention that he was drunk, or suspected of being drunk, at the time he committed the crime of which he was accused. For example, in April 1843, after being charged with drunkenness and using ‘epithets not of the most choice description’, O’Grady appeared before the bench. The Melbourne Times recorded that he ‘scratched his head, the infallible resource to which embarrassed people have recourse, and admitted the drunkenness’.[8] This description, so early in Grady’s career as a nuisance whose ‘love of fun and whiskey is well known’,[9] foreshadows the playful tone that the press would continue to take when reporting his crimes and misdemeanours. According to press representations, his crimes were rarely taken seriously, and his befuddlement, outbursts, and colourful use of language were presented as a form of entertainment for newspaper readers.

Employed as a night watchman, O’Grady saw his work as being ‘in the public service’, for, as he put it, ‘many a dark and dreary night have I paced the dismal streets, protecting your lives and property from the depredations of the midnight robber and the assassin’.[10] He wrote repeatedly to Charles Joseph La Trobe, the superintendent of Port Phillip, seeking employment with the police.[11] Although his letters were eloquently written, with penmanship quite unexpected from someone of O’Grady’s class and reputation, the differing hands and spelling evident in the letters suggest that O’Grady may not have written them; like most convicts, he was probably illiterate. He was eventually appointed a special constable—a position like a deputy, rather than a regular constable; however, his appointment was short lived. According to contemporary press accounts, O’Grady’s employment was terminated due to continuing bouts of drunkenness as well as his own penchant for criminal acts. The Port Phillip Gazette reported that, ‘by some means, a notorious character named Michael Grady alias Big Mick, has been appointed a special constable, and within the last week he has been before the bench for improper conduct twice’.[12] He was finally dismissed from his position for constantly bickering with another special constable during the middle of the night and disturbing the peace.[13]

O’Grady’s treatment by the press provides insight into the way that certain characters in Melbourne, particularly those that might be termed ‘larrikins’, were tolerated and even indulged, by the authorities and, more significantly, by the media. As recently as the 1970s, James Murray—in Larrikins: 19th century outrage—regarded larrikins as social terrorists, a group he ‘equated with the Irish immigrant who has brought such antagonism to the country’.[14] In Larrikins: a history, Melissa Bellanta dates the appearance of the term ‘larrikin’ to the 1860s, with its first appearance in the press in 1870.[15] According to Bellanta, ‘to be a larrikin is to be sceptical and irreverent, to knock authority and mock pomposity’. O’Grady epitomises this characterisation.[16] Bellanta was primarily looking at a later period; however, it is arguable that the larrikin of Australian lore has its roots in figures such as Big Mick.

Numerous contemporary historians have examined the prejudice towards Irish immigrants by English settlers in early Melbourne. As Raelene Frances observes, the Irish were routinely portrayed as ‘dirty, drunken, lazy, emotional, dishonest and addicted to fighting and the singing of mournful ballads’.[17] In The Irish in Australia, Patrick O’Farrell relates a stream of complaints made during the 1830s and 1840s, such as that ‘Australia was being flooded with ignorant, uncivilised, degraded Catholic paupers’.[18] The Reverend John Dunmore Lang’s 1841 pamphlet, The question of questions! Or, is this colony to be transformed into a province of the Popedom? A letter to the Protestant landholders of New South Wales, was typical of such complaints. Lang proposed measures to reduce the number of immigrants coming from undesirable areas of Ireland, which he saw as ‘the strongest holds of popery, bigotry, superstition, and immorality, in the British Empire’.[19] The Irish were present at both the top and bottom of the colony’s growing social establishments, separated by gulfs in ‘education, social background, sophistication, and, usually, religion’.[20] Notably, many of the colony’s lawmakers shared Irish heritage, with the policing of Melbourne modelled on that of both the London Metropolitan Police and the Irish Constabulary.[21]

Highlighting his Irish background, Big Mick was generally quoted in dialect, rather than paraphrased. This added to the charm—relative to stereotypes of the Irish working class—with which his character was imbued. For example, the Port Phillip Gazette recorded that he sang ‘Oh nanny wilt thou gaho wi’ me’ in court while looking ‘wistfully’ at a goat whose ownership was in dispute (and which he was accused of stealing).[22] This kind of reporting indicates that the press and the law indulged O’Grady’s colourful behaviour. That O’Grady was in a state of ‘effervescence’, and that it took ‘a few magisterial frowns to keep the hot blood of the O’Gradies from boiling over’, was acceptable because he put on a show for the court and the press.[23]

The timing of O’Grady’s crimes, as well as his appearance before the police court and mayor’s court rather than the Supreme Court, means that there is dearth of official records detailing his encounters with the law. Victoria did not have a Supreme Court until William a’Beckett and Redmond Barry first sat on its bench on 10 February 1852.[24] While records of Victoria’s superior courts are largely well maintained, records documenting matters of the police and magistrates courts are far less detailed or complete. VPRS 51 contains the deposition registers from 28 April 1845 to 23 October 1855; however, the records from 1847—the year when Grady’s criminal exploits were at their height—are absent. We know that the police court at this time was ‘a temporary wooden building insufficiently small’.[25] These conditions are unlikely to have fostered good record keeping practices, a potential factor in the loss or destruction of many records of lower courts, including those concerning O’Grady.

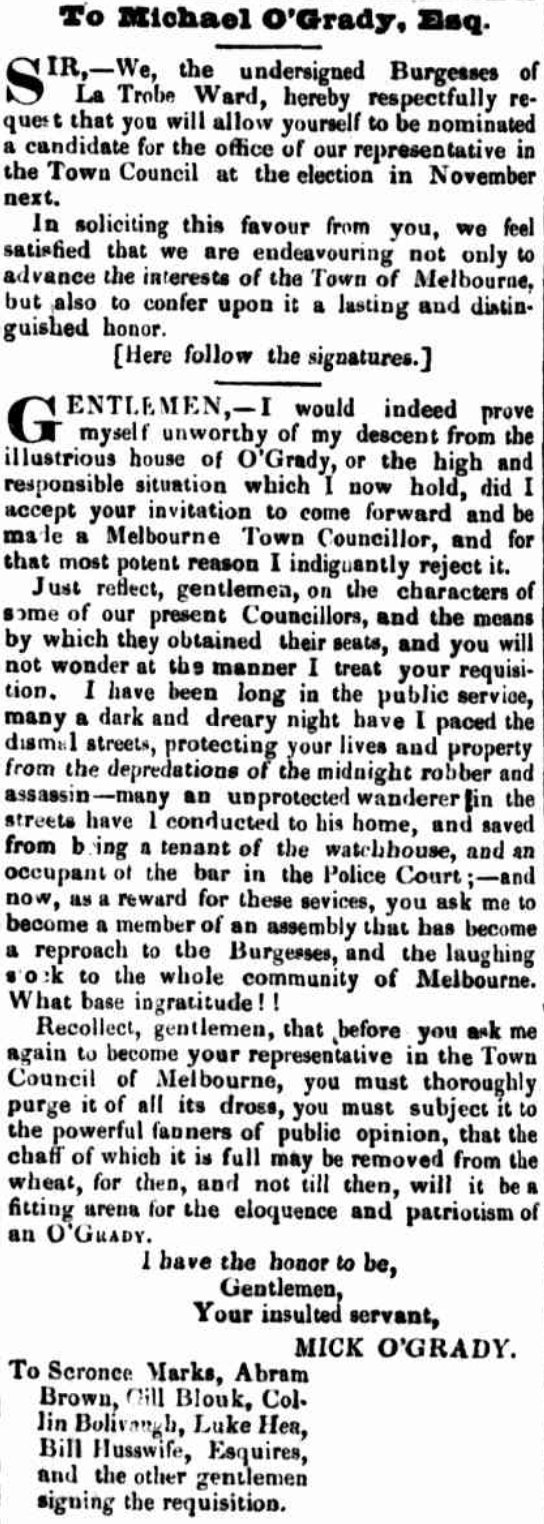

Something of a local celebrity, Grady’s notoriety purportedly led to a formal request by the burgesses of La Trobe Ward that he accept a nomination for the Melbourne Town Council in 1846 (see Figure 1). Grady ‘indignantly rejected’ the nomination, stating that it represented ‘base ingratitude’ for his services, and that the council was not a ‘fitting arena for the eloquence and patriotism of an O’Grady’.[26] Later, reporting that his job as night watchman was in jeopardy, he averred that he was willing to submit to the ‘degradation of the name of O’Grady’ and allow himself to be elected to council.[27] However, there is no record of him running for council. The entire incident may have been in jest—a joke run by the Argus; yet, the fondness with which Grady was regarded at the time, at least by the local media, remains evident.

Figure 1: Michael O’Grady is encouraged to run for a position on the town council, Argus, 13 October 1846, p. 3.

The theft of the blunderbuss from the shop of French watchmaker, Monsieur Charet, appears to have been the high point of Grady’s career as a criminal and celebrity. Grady examined the gun ‘very coolly, put it under his arm’ and crossed the road to the pub. Charet attempted to retrieve the gun in a polite manner, and was rebuffed by Grady with a ‘coarse brutality of the lower order of Mick’s countrymen’.[28] Charet sought a warrant from the police, stating that ‘from what he knew of the prisoner’s character, as well as by general report, he had no doubt that he would commit some act of violence if he encountered him in the public streets’.[29] Sergeant King, the owner of the gun, questioned Grady when he saw him with it and, according to the Argus, was told by the drunken Irishman that it was obtained from Charet’s shop.[30] One of the jurors asked whether Grady was insane, as he had seen him ‘walk about in a furious state, but this might have been from the influence of liquor’.[31] Reflecting Grady’s reputation and level of esteem, he was found not guilty and ‘departed, greatly pleased, no doubt, at his lucky escape’.[32]

The theft of the firearm and subsequent legal proceedings led to days of coverage in the Port Phillip Patriot, Port Phillip Gazette, Melbourne Argus and Geelong Advertiser. The Geelong Advertiser took a serious tone in its reporting, noting that ‘Michael Grady, charged with stealing a blunderbuss, was found not guilty, and discharged’.[33] By contrast, Melbourne’s papers, seemingly relying on the infamy of the accused, used the events to entertain their readers. The Port Phillip Patriot quoted Grady’s wife as saying that a ‘more correcter [sic]’ man than her husband had never lived, thereby playing to audiences’ preconceptions about Grady’s background—Irish, uneducated and lower class. The paper continued in this vein, describing O’Grady’s defence (or lack thereof) in whimsical terms: ‘Mr. O’Grady, for the first time in his life since he learnt the use of his tongue, was dumb; he had not one word to say in his own behalf.’[34]

There are few modern analogues for the kind of esteem O’Grady enjoyed in the days when Melbourne was still a small town. Perhaps we could look at the modern fascination with criminality in Melbourne through television programs such as Underbelly, or through the celebrity of figures such as Chopper Read, immortalised in the film Chopper; however, to a great extent, this fascination is based on a fictionalised portrayal of brutally violent but charismatic figures. The clear affection and tolerance shown towards Michael O’Grady—evident in the press and in the sentence of ‘not guilty’ delivered by the jury when all evidence appeared to indicate the contrary—is not replicated in these modern examples. A better comparison is Ned Kelly; in particular, Ned Kelly’s posthumous public reputation as a folk hero as well as Australia’s ‘sole national hero’.[35]. The violence and criminality of his actions is either downplayed or seemingly outweighed by his appeal as an Irish–Australian larrikin who challenged the establishment.

The exploits of Michael O’Grady came to an end in September 1847. The reports of his death failed to make a significant mark in the newspapers. The Melbourne Argus was the only newspaper that sought to memorialise him:

Yesterday morning an individual of some notoriety, no other than Mr. Michael O’Grady alias Big Mick, paid the debt of nature—his death having been greatly accelerated by habits of intemperance.[36]

No tear-soaked obituaries (or tales of doleful mourners drinking to his memory) filled the papers. With his death, the press’ fondness for his antics dissipated as though it had never existed and he disappeared from the public eye. A local charity paid for his burial in the Old Cemetery, but his grave was not among those recorded for posterity when the Queen Victoria Market was built over the site.[37] There are extensive records held by PROV concerning the Old Cemetery, including records of exhumed bodies and plans, but it is impossible to know the identities of those buried on the site due to a fire in 1864 that destroyed the building where the records were kept.[38]

In 1888, Edmund Finn, writing The chronicles of early Melbourne, recalled that Big Mick ‘skulked and begged for free drinks’ at the back doors of public houses.[39] Apart from this short paragraph, there appear to be no other references to O’Grady in the narratives of early Melbourne. Instead, he has remained largely forgotten in the popular consciousness. Thankfully, traces of his life can still be found at PROV and in newspapers. Big Mick played a modest but notable role in the emerging social character of Melbourne; by garnering the sympathy of the populace concerning lower class Irish ‘larrikins’, his antics may have helped to lay the groundwork for folk heroes such as Ned Kelly. Perhaps now, at long last, the ‘redoubted Mick’ can regain some of the renown (and infamy) that he held in life.

Endnotes

[1] ‘A night watchman in trouble’, Port Phillip Patriot and Morning Advertiser, 11 March 1847, p. 2.

[2] SLQ, Roll 89, HO11/8, p. 238.

[3] ‘Principal superintendent of convict’s office, Sydney’, New South Wales Government Gazette, 31 October 1832, p. 381.

[4] PROV, VPRS 19/P0001, bundle 1844/1828, 44/1785.

[5] ‘Government gazette notices’, New South Wales Government Gazette, 17 April 1839, p. 457.

[6] ‘Police intelligence’, Port Phillip Patriot and Melbourne Advertiser, 29 June 1840, p. 3.

[7] Robyn Annear, Bearbrass: imagining early Melbourne, Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 2005, p. 59.

[8] ‘Police intelligence’, Melbourne Times, 29 April 1843, p. 2.

[9] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Port Phillip Gazette and Settler’s Journal, 13 March 1847, p. 2.

[10] ‘To Michael O’Grady, Esq.’, Melbourne Argus, 13 October 1846, p. 3.

[11] PROV, VPRS 19/P0001, bundle 1844/1828, 44/1785; PROV, VPRS 19/P0001, bundle 1844/2124, 44/2124; PROV, VPRS 19/P0001, bundle 1844/2132, 44/2132.

[12] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Port Phillip Gazette and Settler’s Journal, 15 October 1845, p. 2.

[13] ‘Local intelligence’, Port Phillip Gazette and Settler’s Journal, 24 December 1845, p. 2.

[14] James Murray, Larrikins: 19th century outrage, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1973, p. 19.

[15] Melissa Bellanta, Larrikins: a history, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2012, pp. 2–3.

[16] Ibid., p. xii.

[17] Raelene Frances, ‘Green demons: Irish–Catholics and Muslims in Australian history’, Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations, vol. 22, no. 4, 2011, p. 444.

[18] Patrick O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, 1993, p. 71.

[19] John Dunmore Lang, The question of questions! Or, is this colony to be transformed into a province of the popedom? A letter to the protestant landholders of New South Wales, J Tegg and Co, Sydney,1841, p. 10.

[20] O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia, p. 93.

[21] Mark Finnane, ‘Law and order’, in eMelbourne: the city past and present, 2008, available at <http://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00839b.htm> paragraph 3, 5, accessed 2 January 2018.

[22] ‘Domestic gazette’, Port Phillip Gazette and Settler’s Journal, 23 August 1847, p. 2.

[23] Ibid.

[24] ‘Our history’, Supreme Court of Victoria, 2017, available at <https://www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au/our-history> paragraph 2, accessed 14 February 2018.

[25] J Porter, ‘Port Phillip, as she is at present’, in Peter Lund Simmonds (ed.), Simmonds colonial magazine and foreign miscellany, Volume 4, Simmonds and Ward, London, 1845, p. 303.

[26] ‘Committal for felony’, Port Phillip Patriot and Morning Advertiser, 12 March 1847, p. 2.

[27] ‘To Michael O’Grady, Esq’.

[28] ‘To the burgesses of La Trobe Ward’, Melbourne Argus, 23 October 1846, p. 3.

[29] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Melbourne Argus, 12 March 1847, p. 2.

[30] Ibid.

[31] ‘Supreme Court—Crown side’, Port Philip Gazette and Settler’s Journal, 17 March 1847, p. 3.

[32] Ibid.

[33] ‘Supreme Court—Crown side’, Geelong Advertiser and Squatters’ Advocate, 26 March 1847, p. 2.

[34] ‘Committal for felony’.

[35] Graham Seal, ‘Ned Kelly: the genesis of a national hero’, History Today, vol. 30, no. 11, 1980, p. 9.

[36] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Melbourne Argus, 10 September 1847, p. 2.

[37] Edmund Finn, Chronicles of early Melbourne: 1835 to 1852 historical, anecdotal and personal, Ferguson and Mitchell, Melbourne, 1888, p. 942.

[38] Godden Mackay Logan, Old Melbourne Cemetery: information collation, stage 2 documentation, draft report, 2017, available at <https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/sitecollectiondocuments/qvmpr-old-melbourne-cemetery-report.pdf>, p. 12, accessed 24 February 2018.

[39] Finn, Chronicles of early Melbourne, p. 942.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples