Last updated:

‘City views: modelling Melbourne at the Royal Exhibition Building’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 21, 2023-24. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Andrew J May.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This article examines the history of the construction of a scale model of Melbourne in 1838 that was made in 1888 for the Centennial International Exhibition, (Royal) Exhibition Building, Melbourne, and its reinterpretation in Clarence Woodhouse’s lithograph Melbourne in 1888, from the Yarra Yarra, often erroneously cited as having been created in 1838. Reception of the model reveals that it held, at times, contradictory meanings for a variety of audiences and was a touchstone for nostalgic reflections about Melbourne’s past, the progressive achievements observable in its present and uncertainties about urban development in its future. With the opening to the public of the Royal Exhibition Building’s dome promenade in 2022, Melburnians can again reflect on a novel city view, note the pace of urban change, and debate the balance between future development and maintaining, through view protection, the Outstanding Universal Value of the World Heritage listed building.

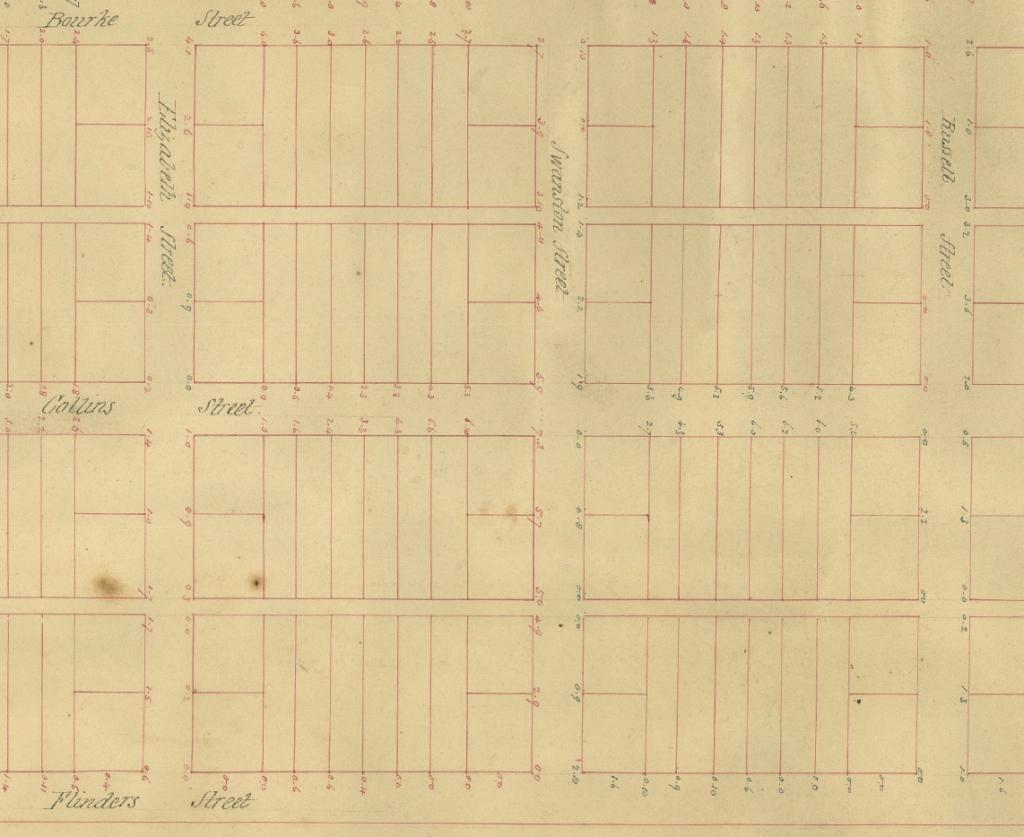

Figure 1: Detail, Wade & Darke, ‘SYDNEYM45; MELBOURNE CITY – SURFACE CONFIGRTN; STREETS’, PROV, VPRS 8168/P0002.

Melbourne in its infancy was, more or less, an act of imagination as much as a real place. When Hoddle’s 1837 grid was pegged out, it was merely the skeleton of a future city, oriented towards the future but only suggestive of what it might become. Weevel, a character in George Henry Haydon’s 1854 novel, The Australian emigrant, having a plan of Melbourne in his pocket, was most curious about the location of its key institutions—the gaol and government house, the barracks and churches, the wharf and the police office—but could not discern them on the ground: ‘in short, where is the town?’ (Figure1). The skipper, in reply, suggested that the plan was not what Melbourne was, but what it was to become: ‘The shade of the largest trees left standing are our churches for the present … That little crib, a short way up from the Yarra, is the custom-house.’[1]

Half a century on from European invasion of the Kulin lands, visitors stared at another miniature simulacrum, a scale model of Melbourne in 1838, comparing it with the city they saw with their own eyes in 1888, reconciling it either with a memory or an impression of what it had once been. In mid-1888, the secretary of the Victorian Railways offered the services of Monsieur JJ Drouhet, a draftsman in their employ, for preparing a model of early Melbourne that was to be displayed at the Centennial International Exhibition. Drouhet spent a month building the 12-foot square model, and it took a number of days to assemble it in situ. The model was to stand on a table high enough for it to be seen by visitors, who would first read it in contrast to the exhibition around it, as an artefact of colonial skill and enterprise as well as an advertisement for the city; and who could then compare the city of the past with the city of its future, observed from high in the dome of the Exhibition Building.[2] The extraordinary model was a hit, Drouhet’s skill and aptitude celebrated in the press of the day as a work of ‘incessant labor and patient care … by which he will always be remembered’.[3] Sometime after the close of the exhibition, however, the model vanished without a trace, its creator soon forgotten. This article tracks the origins of the model’s construction, reckons with the distance between its present in the 1880s and the past it represented, notes its afterlife in a popular lithographic representation of old Melbourne, and further reflects on new meanings ascribed to the view from the dome promenade—and views of the dome itself—in the context of the Exhibition Building’s World Heritage inscription and the dome promenade’s reopening to the public in October 2022.

A Frenchman in Victoria

Justin Joseph Drouhet was born in 1830 at Rochefort, a coastal town in south-western France, into a wealthy and well-connected family. His wife Marie Berthe, whom he married in Paris in 1858, was the daughter of a merchant and shipbroker with links to the Mauritius trade. Justin had a bachelor of arts from the University of Paris and studied engineering at the École Polytechnique.[4] In 1863, he was listed as an employee of the Chemin de fer de l’Est (a French railway company) in the Champagne region of north-central France.[5] On 16 September that year he arrived in Melbourne with his wife and three children on the Moravian.[6] The ensuing five years saw Drouhet embark on a range of ultimately unsuccessful commercial ventures importing a range of French goods to Melbourne, including wines and spirits, clocks, preserves and pianos.[7] In and out of the insolvency court,[8] Drouhet took his growing family to Ballarat and tried his hand as a clerk, miner and teacher of French and painting, but financial woes forced the family back to Melbourne. On 11 October 1873, Drouhet applied in writing to the engineer in chief, Victorian Railways, for a position as a draughtsman.[9] A few days later he was on the books as employee no. 1926, with the caveat that, because his appointment was not to an office under the Civil Service Act, he was not to make any claim on Victorian Railways whenever his employment might be terminated.[10]

By the start of 1888, Justin Drouhet, then approaching 60 years of age, had been in Victoria for 25 years, had lost two wives and five children along the way, much of his own and a little of other people’s money through speculative business ventures, and something of his own reputation. The colony of Victoria was poised to mount an appraisal of its achievement and celebration of its assets in the shape of the Centennial International Exhibition, measuring its progress against a national baseline of 1788, and inviting the world—if not the other Australasian colonies—to take note. With their ground zero in the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations at London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, international exhibitions and world’s fairs proliferated in the second half of the nineteenth century as complex events combining place marketing, technological diffusion and commercial expansion, with intercultural knowledge, assertions of regional and national identity, and the consolidation of imperial ideologies and networks, including at Paris (1855, 1867, 1878), London (1862), Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876) and Barcelona (1888).[11] Prior to 1880, Melbourne had hosted five intercolonial exhibitions since mounting its first in 1854 in a building in William Street, ‘typically, edifying “national” displays of manufactures, assets and achievements; and preliminaries to participation in events overseas’.[12]

At a meeting of the Melbourne exhibition’s executive commissioners on 6 March 1888, prosperous merchant and politician Frederick Thomas Sargood suggested the idea of commissioning the Melbourne City Council to make a model of Melbourne in its early days. His Honour Mr Justice Higinbotham, president of the committee, suggested that the 1837 Crown Lands Department plan of Melbourne in its infancy might provide an uncomplicated basis for the model’s design, pointing to a model of Manchester that had been exhibited at that city’s exhibition the previous year. The executive committee concurred, and further moved that the Tramway Company be asked for a model of the city’s tramway system, and that the Melbourne Harbor Trust be asked to provide models of the Yarra River showing improvements: ‘Mr J. Munro, in seconding the motion asked if it were possible also to introduce the smell of the Yarra into the models. (Laughter).’[13] A week later, a letter was dispatched to the City of Melbourne requesting that the ‘City Council will contribute to the Exhibition a model of Old Melbourne taken from one of the earliest plans’. The council referred the query to the town clerk, EG FitzGibbon, to ascertain costings. FitzGibbon soon received a positive reply to a letter to the secretary for railways dated 29 June requesting permission for Monsieur Drouhet to be seconded for the purpose, expecting that the task would take around a month to complete.[14] By 9 July, FitzGibbon reported that preparation of the model by Mr Drouhet of the Railway Department had been formally arranged at a cost of £70.[15] The commission, perhaps, came as something as a fillip for Justin Drouhet, who had lost another daughter Alice, aged 19, to pneumonia on 22 May, the sixth of his children to predecease him.[16]

Drouhet’s skills as engineer and draftsman had been well honed in the employ of the railways, and, prior to this commission, he had made models of the old and new Spencer Street railway stations.[17] While scale modelling was the stock in trade of the toy industry, it had a deeper history in military and architectural survey and reconnaissance. Maquettes and scaled relief maps of French fortifications were crafted from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, some of which survive in the collection of the Musée des Plans-Reliefs in Paris.[18] In Victoria, National Museum director Frederick McCoy commissioned Swedish-born miner Carl Nordström to construct scale models showing a range of gold mining techniques. A large model of the Port Phillip and Colonial Gold Mining Company’s works was displayed at the 1861 Victorian Exhibition in Melbourne, and later shipped to London for the 1862 International Exhibition.[19] Constructed between 1856 and 1859, nine of Nordström’s models survive.[20] In the museum context, the diorama was to become the most popular and ubiquitous presentation medium.

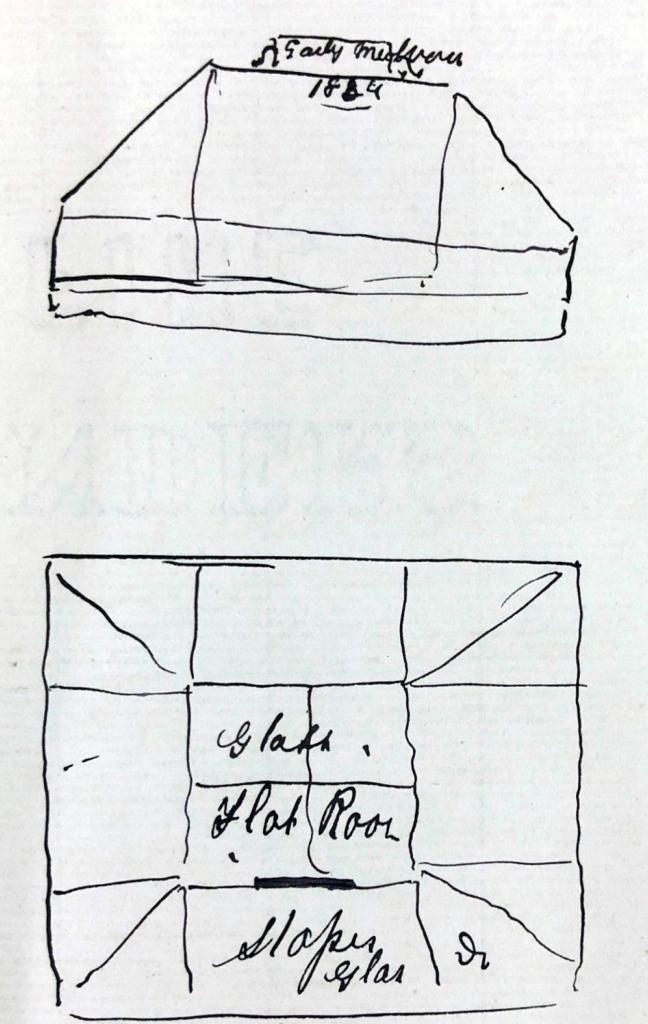

The genre of the miniature was age-old, familiar and explicit in the grammar of the exhibition itself. Seeking to represent the world at large, many exhibits reduced the scale of landscapes and material culture by artifice and imagination. Drouhet set about gathering material on which to base his model; the secretary for lands at the Department of Lands and Survey offered him ‘all possible assistance’, while Thomas Bride, chief librarian of the Melbourne Public Library, on behalf of the trustees, granted access to any plans, documents or books in the library’s collections that would assist in the model’s conception.[21] With the model shaping up, Drouhet was concerned that sufficient space had not been provided at the exhibition for its accommodation. It would, he noted, require a number of days to assemble the model inside the Exhibition Building.[22] On 27 July FitzGibbon informed Drouhet that a space had been allocated, and that Drouhet should get in touch with commissioner Lambton L Mount who would point out the exact position.[23] The exhibition opened its doors on 1 August 1888, but installation of the model was delayed due to space issues; correspondence on the subject of the showcase for the model in early October suggests that it was likely in situ in the latter part of that month (see Figure 2).[24]

Figure 2: G Downing to EG FitzGibbon, 5 October 1888, 1888/1946, PROV, VPRS 3181/316.

Models, along with plans and drawings, were the stock in trade of the salesman. A perusal of the exhibition catalogue reveals the extent of shrinkage—how else would a world of goods fit into a building, however magnificent and expansive the pavilions and courts of the Exhibition Building proved to be? J Perry exhibited a model of Niagara Falls; S McDonald exhibited a model of the Yarra River showing the Harbour Trust improvements; E Rossner produced a model of the mineral baths of Salzerbad-Kleinzell; and L Coen got up a model of Sandringham, or Marlborough House, made of cigarettes. Visitors could marvel at models of the Jenolan Fish River Caves, the Eiffel Tower built out of champagne bottles (though the French court was a disappointment),[25] St Louis brewery, the Adelaide water supply, and fortifications at home and aboard—from the Langwarrin military camp to the Krischen redoubt and infantry trenches of the Turkish defence of Plevna. Despite fears that it might disclose the city’s strategic defences to the Russians, a 13 x 7 feet model of Sydney Harbour and environs in the New South Wales Court ‘accurately delineated the natural features of 135 square miles of country, together with towns, roads, shipping, etc’.[26] There were models of balloons and bridges, fountains and fences, guns and gold mines, houses and haystacks, school and ships, pipe cleaners and ploughs, stables and staircases, all to be peered at as simulacra of invention, efficiency and progress (see Figure 3).[27]

![Figure 3: Detail of exhibit, Centennial International Exhibition, Melbourne, 1888. Glass plate negative, NRS-4481-4-214-[AF00197928], NSW State Archives and Records.](/sites/default/files/files/Provenance%202024/MayAJ-F03.jpg)

Figure 3: Detail of exhibit, Centennial International Exhibition, Melbourne, 1888. Glass plate negative, NRS-4481-4-214-[AF00197928], NSW State Archives and Records.

Justin Drouhet’s model was nestled in the Victorian Court, listed but unattributed on p. 599 of the catalogue:

Victorian Exhibits

II: Education and instruction—apparatus and processes of the liberal arts.

Class 11: General application of the arts of drawing and modelling,

No. 280: Melbourne City Council, Model of old city of Melbourne.

Descriptions of the model in the press appeared in Table Talk on 5 October and the West Australian on 27 October. The latter described it as ‘one of the most interesting exhibits in the Exhibition’:[28]

It is about twelve feet square and the surface of the ground is almost entirely covered with scrub. John Fawkner’s house, and Batman’s house and garden are amongst the few habitations shown in the model. Pictures of Melbourne in 1838 and in 1839 hang in the Victorian Loan collections.[29] In these where Queen’s Wharf is now, the Yarra appears as a rural stream, running between tree-covered banks. The sight of these pictures and of the ten-story buildings that are beginning to appear in the streets of this city furnishes food for much reflection.

The distance between past and present revealed slippages in memory as well as original errors of representation. Analysing a contemporary view of Melbourne in 1839 in preparation for construction, Drouhet had consulted with ‘several old colonists who have recognised their early residences’ and determined that ‘the view is far from being correct and that the person who sketched it used a good deal of imagination’.[30] Peering through the glass cover that protected it, observers were astonished at its Lilliputian world. Here were the residences of early settlers John Pascoe Fawkner, Captain Lonsdale and John Batman (‘faithfully set forth in the model, even to the cabbages’); there was Mrs Cook’s school for ladies, shops and a little church, hotel and hospital, prison, the soldiers’ barracks and the government offices.

However tangible and intriguing an artefact, the model held contradictory meanings, resonating differently for a variety of audiences. Mayor of Melbourne Benjamin Benjamin was one of two compulsory members of the corporation on the 16-member Exhibition Commission selected by the governor-in-council to orchestrate the exhibition. Dominated as it was by city property owners, businessmen and traders, it was clearly in their best interests to present the Melbourne of 1888 in a favourable light. The incumbent city fathers sought to create a physical and visual means of comparing and contrasting the character of the living city they were soon to present to the critical gaze of intercolonial and overseas visitors with a static representation of that city as it was prior to the goldrush and subsequent boom decades. The potential audience could not be underestimated; as it transpired, the exhibition, model included, was seen by more people than any other event in nineteenth-century Australian history.[31] There was, perhaps, a tension for the commissioners and the corporation between their overt pride in what these self-important civic leaders wished to present as their now progressive, mature, sophisticated and civilised ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ and their well-concealed discomfort and perhaps even guilt at the extremes of its physical reality. However, for some of its citizenry at least, the crowded, smoky, noisome and unsanitary metropolis produced a more anxious and less covert nostalgia for a city lost. General ambivalence about the price of progress and, perhaps, the moral foundations of the land boom in particular was reflected more broadly in history and popular culture.[32] Seen through the selective haze of 50 years of significant social and economic upheaval, and of its rapid physical transformation, ‘early’ or youthful Melbourne could be viewed as idyllic in its rustic simplicity—the model of Melbourne as it was in 1838 experienced as a manifestation of an idealised Golden Age, as ‘natural’, untouched by knowing materialism and urban squalor. It could also be viewed as a primitive backwater awaiting the magical metamorphosis that only prosperity, industry and population increase could bring. It may be reading too much into the scant documentation to interpret the commissioners’ choice of the word ‘old’ as negative and a journalist’s choice of ‘early’ as positive in their respective descriptions of the subject and object of Drouhet’s model.

A model was something constrained and contained, not living and changing; it was the known as opposed to the unknown and difficult-to-control future. The rapidly growing and changing city, which was, in many quarters, also decaying, was both exciting and frightening. Drouhet’s model inspired in the Australasian’s reporter a self-aggrandising assertion of the gains that had been made by those who had made their fortunes from land: where once were clay pits and drying sheds on the south side of Flinders Lane between Swanston and Elizabeth streets, now were ‘palatial warehouses … worth many millions’. Reflecting on the changes in the topography and functional geography of the town, the article reminisced that Elizabeth Street had once effectively been a small stream, and that ‘the nucleus of an incipient township’ had been around the intersection of Collins and Queen streets. Drouhet’s construction included over 3,000 individual miniature trees and around 200 houses. Made of glass, the Yarra River had four vessels floating on its crystal waters and ran like a silk border between the town and the marshland to its immediate south. Popular tropes of progress—the city as a civilised bulwark against the threat of the bush—were romanticised in the Australasian’s observation of Drouhet’s version of the nascent township:

Such of the streets as had been aligned were only bush tracks with the hacked or charred stumps of venerable gum-trees still embossing their dusty surface; and to the northward these tracks gradually became more indefinite, and finally lost themselves in the green sward of the bush.[33]

This idea of progress acknowledged that Melbourne’s long boom had stripped its immediate environs of accessible resources for firewood and construction: the splitters and wood-carters of 1838, ‘looking around them, and seeing the woodlands stretching away for miles in every direction … must have regarded the supply as practically inexhaustible’.

The Table Talk correspondent had clearly spoken with Drouhet himself, and was more personalised in the praise it heaped on his technical skill:

the exact reproduction on a miniature scale of the appearance Melbourne had 50 years ago … a work of art, both on account of the skill displayed in keeping the respective heights of the buildings in proportion to the scale of measurement, and the verisimilitude which the substances employed bear to real houses, ground, water and trees. When it is considered that the roof of the Shakespeare Hotel is an inch and a half from the ground, one can get a fairly good notion of the incessant labor and patient care which M. Drouhet has bestowed upon the whole plan.

The Argus saw the express purpose of the model as being to ‘effectively illustrate to visitors the rapid progress which the colony had made during the fifty years of its existence’.[34] The Centennial Magazine expressly invited real-world comparison of the old and the new (see Figure 4):

A model of old Melbourne is interesting, because the visitor, after seeing it, may go to the parapet of the dome and obtain a very good bird’s-eye view of the Melbourne of to-day; a great deal of the newer suburbs to the south-east being lost, however, in the rolling contour of the land.[35]

Figure 4: ‘Melbourne, Australia, looking towards the southeast from the exhibition dome’, Keystone View Company, c. 1908, Library of Congress, available at https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2019630108, accessed 13 January 2024.

Access to the dome’s viewing platform was to be had by a specially installed lift.[36] A Leader columnist took a more explicit opportunity not just to remark on Melbourne’s extraordinary metropolitan growth—‘The Melbourne of that day differs almost as much from the Melbourne of our time as does the London of Queen Elizabeth from the London of to-day’—but also to link its uninterrupted suburbia overflowing to the north and south ‘with scarcely a break’ with ‘the coast fringed with rapidly-growing municipalities’, to land costs and urban infrastructure. Here was an opportunity to couple the relative land valuations across the metropolis in terms of ‘advance, rising land costs and the land boom’ to the ‘princely revenues’ of the municipalities: ‘it may reasonably be asked’, the correspondent chided, ‘is all being done that can be done for the comfort of ratepayers who so liberally subscribe?’ The city’s progress was therefore explicitly measured against the ‘great blot’ (the want of a sewerage system), poor drainage, pollution of the Yarra and sea beaches, and the need for beautification of streets and recreation grounds.[37]

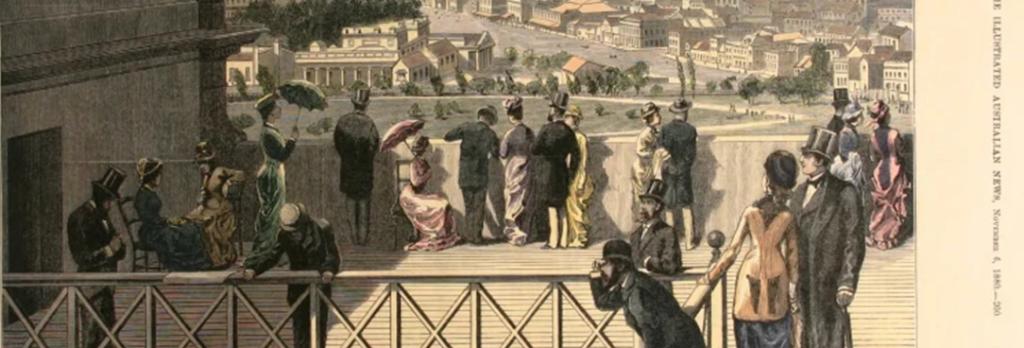

Drouhet’s model was an overt prompt for the 1888 visitor to reflect on the changing meanings of Melbourne and its development, but a few months prior to the opening of the previous exhibition in 1880, members of the public had also, for a short time, been allowed to access the elevated portions of the building to view the city below. In 1888, a Waygood Patent Safety Lift enabled public access to the viewing platform; in 1880, this was achieved with a fair measure of bravado by climbing a staircase to the first level balcony fronting Spring Street, a further flight of stairs to a second landing, an exposed 56-foot perpendicular iron ladder to the dome, and finally by means of an inner stairway to a small octagonal apartment (Figure 5).

Figure 5: ‘A view from the balcony’, Illustrated Australian News, 6 November 1880, p. 200.

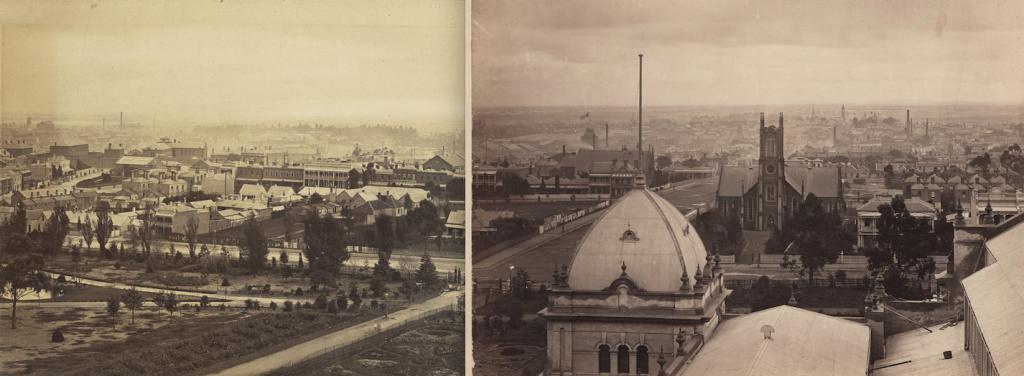

Around 1 in 20 visitors ascended to the highest point, but whether viewed from the balcony, the gallery, the base of the dome or the eagle’s nest, ‘everything has a new and bewildering look, well-known localities having lost for a time all their points of identity’. Here the city appeared in a glance as ‘one connected whole’. The novel perspective gave the viewer a sense of a homogenised city when compared to their everyday knowledge of ground-level demarcations of suburb or precinct. Church spires and factory chimneys were specific reference points, but the fact that Fitzroy, Carlton and Hotham (North Melbourne) were in most respects indistinguishable from Melbourne proper—‘no more built over, and no more populous’—was a little confusing in an age before the density of skyscraper development gave aerial definition to the Hoddle Grid (see Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6: Composite panoramic sequence of view looking west from the roof of the Exhibition Building, Carlton Gardens, with Rathdowne Street running across the middle distance and St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church and Manse observable to the right of the dome, c. 1880 – c. 1889, State Library of Victoria, H141261 and H4570, attributed to Charles Nettleton.

Figure 7: Composite panoramic sequence of previous view, compiled by author, March 2022.

This same Argus article that revelled in the view from the Exhibition Building in 1880 (‘City and suburbs seen from two towers’) made an excursion to the Beaconsfield Tower, a 200-foot-high wooden structure built on Doncaster Road by Alfred Hummel in 1878 (demolished in 1914). Here, Melbourne itself became an object of view: ‘That distant city can be seen away down below towards the edge of the bay, and a clear view can be had over the tops of its tallest spires and around on all its suburbs.’ Where nostalgia for England elicited rustic equivalences (‘A lake or two or the view of a river is all that is needed in the scene here at Doncaster to complete the illusion that what is seen is British and not Australian scenery’), the broad scale of the urban as viewed from the Exhibition Building encouraged comparison of Melbourne as a ‘growing Babylon’ to American exemplars:

So seeing it and thus judging of it, the supposed stranger would have, as he needs must have, an enlarged idea of the claims of Melbourne as a hugely-grown and rapidly growing city. It is, so seen, as large as any city of five hundred thousand that can be named, and in so saying one thinks of American cities of that size that have been seen from similarly elevated positions.[38]

No sooner did the distant city become observable as a material artefact, at whatever scale, than real estate advertisements promoted the virtues of a view. A grand building allotment commanded ‘a splendid bay and city view’ (1866);[39] sites in the Doutta Galla Estate between Ascotvale and Moonee Ponds had ‘Splendid Views of the Bay, City, Racecourse, and Surrounding Country’ (1882);[40] the aspect from Clifton Hill was ‘Commanding, Elevated, Invigorating … Views Phenomenal of City, Town, and Country’ (1885);[41] an orchard in Mitcham boasted ‘splendid mountain and city view’ (1887);[42] while a superior brick villa in Hawthorn offered ‘landscape and city views’ (1888).[43]

Seen from either of its western (Batman’s) or eastern hills, the view of Melbourne from mid-century could be contained within sight, and enhanced when the vision was nocturnal; during celebrations for the Queen’s birthday in 1863, ‘when the breeze had fallen away, the city, viewed from the crest of either the Western or Eastern hill, presented a noble spectacle. The light which burst from almost every house, and which glared up from almost every street, rendered the plan of the city luminous.’[44] Despite Melbourne’s relatively low scale by 1889, the view from a distance drew another observer’s attention to unsightly irregularities in height along the city’s streetscapes, with a prescient observation that ‘Babylonian towers’ would be the logical product of exorbitant ground rents. While the fear of being trapped by fire, storm or earthquake made the prospect of living ‘at such a perilous elevation’ singularly unattractive, the sole boon of these ‘sky-parlors’ was ‘that the higher the citizen climbs to his nocturnal perch, the better chance he has of escaping the noxious effluvia of the world beneath … in one of the foulest smelling cities of the world’.[45] By the latter decade of the nineteenth century, there were fewer than a dozen buildings in the central city reaching 10 storeys, the Australian Building at the corner of Elizabeth Street and Flinders Lane (1889), at 12 storeys, being Australia’s tallest. Building height limits introduced in 1916 limited office blocks to 132 feet, though turrets, towers and masts extended their vertical range. The sight of church spires may have drawn the nineteenth-century eye to the city centre, but the view of the city as a silhouette against the skyline was the quintessential product of the skyscraper age that accelerated in Melbourne from the late 1950s.[46] Melbourne, viewed at distance from a novel height in the 1880s, was at once perplexing and revelatory, disrupting ground-level common sense about the city’s social geography while at the same time expanding its potential as much as extending its physical dimensions.

Afterlives: Melbourne ‘1838’

The Centennial Exhibition concluded at the end of January 1889. Over coming months, products were packed away, the bunting came down, but the fate of the model remains a mystery. Minutes of the meetings of the exhibition trustees (some of which are missing or fire-damaged) give few specific clues, though, after they requested it for their ‘permanent collections’, the model was formally presented to the exhibition trustees by the City of Melbourne in March 1889.[47] Drouhet had received permission from the City of Melbourne to photograph the model, add a key, and sell reproductions to help make up his financial losses, having forgone his railway salary to work on the model.[48] It is unclear if he did so; other correspondence suggests that the City of Melbourne paid Drouhet’s salary while he was on leave from the Railway Department.[49] A photograph of the model was taken on 25 March 1889 by Baker and Farquhar of Austral Works in Abbotsford, photographic printers to the Victorian Government, with the intention that it be sent as part of a consignment including other views of Melbourne to Paris (Universal Exhibition 1889) and Dunedin (New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition, November 1889 – April 1890),[50] but it is not listed as one of four views exhibited by the firm in Paris and its current whereabouts is unknown.[51]

If the model itself did not survive, in an odd reversal of representation, it had an afterlife in an image that is commonly reproduced as if it had been drawn in 1838, rather than being a nostalgic artefact of the 1880s (see Figure 8).[52]

Figure 8: Detail, Clarence Woodhouse, Melbourne in 1838, from the Yarra Yarra, State Library of Victoria.

By the 1870s, settlers like hotel-keeper and water-colourist WFE Liardet, who came to Melbourne in 1839, were returning to nostalgic views of the town’s early years.[53] Whether topographical, bird’s-eye, panoramic or isometric, broader nineteenth-century views of Melbourne drew on a range of picturesque conventions and popular (or indeed imaginary) vantage points to encode the city’s progress, pride and prospects.[54] These in turn harked back to a long-established pictorial tradition of townscape depiction that proliferated from the fifteenth century in Europe. City portraits, in woodcuts and engravings, were indeed ‘one of the most popular categories of Renaissance print culture’, tapping into a public interest in knowing about foreign places, contextualising global news or intelligence, visualising mercantile and cultural networks, and, above all, ‘publicly [proclaiming] the splendors of one’s own city’.[55] Their rhetorical purpose in idealising urban power and prestige was bullish, their geographies symbolic as much as accurate, as ‘squares become larger, streets wider, and public buildings taller’.[56] The overreach of Nathaniel Whittock’s 1855 etching of Melbourne was a case in point in a century in which the burgeoning mass circulation of newspapers and journals reproduced urban imagery from cities across the British world competing for labour and capital and seeking markets for their agricultural productions and manufactured wares. It exalted to a British audience the progress of a frontier town yet two decades old in its depiction of key buildings, transport infrastructure, a bustling river port and the original Exhibition Building. Melbourne Punch was sanguine in its appraisal: ‘we have never met with a more thoroughly entertaining work of fiction than this verdant view of the Utopian city of Melbourne’.[57]

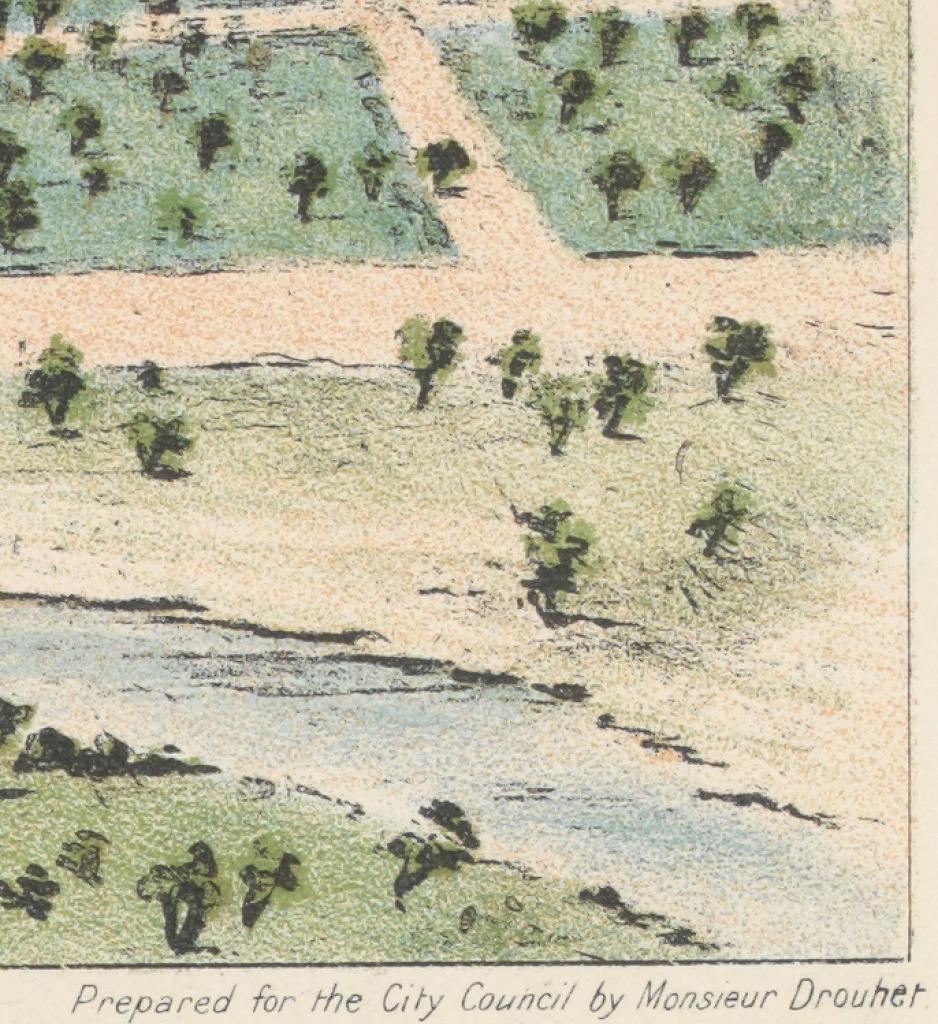

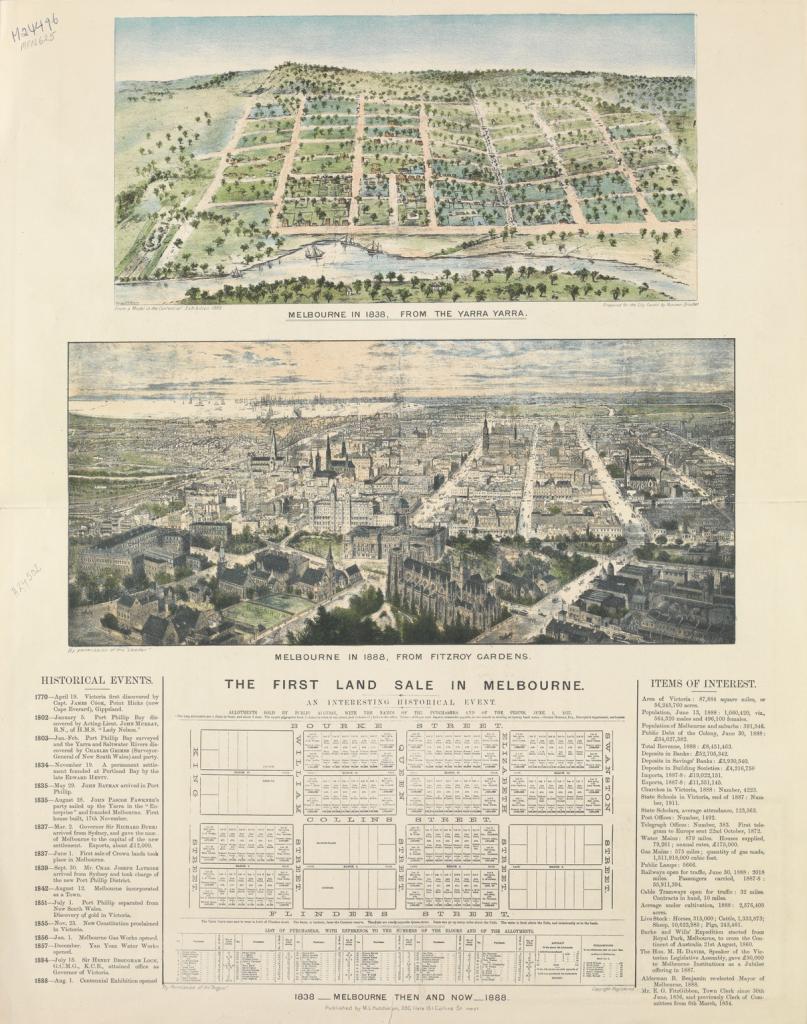

Drouhet’s model became the basis for Clarence Woodhouse’s lithograph Melbourne in 1838, from the Yarra Yarra, published by ML Hutchinson as 1838—Melbourne then and now—1888 (Figure 9).[58] A large double-sheet promotional ‘booklet’, printed on both sides and originally folded like a modern map, reproduced Woodhouse’s coloured lithograph at the top, with acknowledgement immediately beneath in fine print: ‘From a Model in the Centennial Exhibition 1888’, ‘Prepared for the City Council by Monsieur Drouhet’. Underneath is a depiction of ‘Melbourne in 1888, from Fitzroy Gardens’ (‘By permission of the “Leader”’), along with a short chronology of ‘historical events’ from 1770 to 1888 and other historical ‘items of interest’, and a map of the first land sale in Melbourne with a table of purchasers. On the second side is a street map of the central Melbourne grid, superimposed on an early topographical map, along with some contemporary advertisements.

Figure 9: 1838–1888 Melbourne then and now together with the first land sale and present value, State Library of Victoria.

Edward Noyce’s 1840 lithograph of Collins Street depicts a small group of Aboriginal people looking down at the burgeoning scene below from the town’s eastern rise. Positioned next to a stand of trees and a tree stump in the foreground margin, their sidelining from the grid is a deliberate exercise in exclusion and was a common visual tactic in cityscape views of the period.[59] In Drouhet’s model and its lithographic echo, the depiction of individual people was more or less inhibited by their scale, but it is the grid itself that is a key instrument of dispossession, a net thrown over stolen land that at once proclaimed authority and masked its violent impositions. In its plentiful displays of Indigenous weaponry, the exhibition itself rendered Indigenous peoples a defeated race. A historical essay in the official record rehearsed the foundation myth of Batman’s treaty that served to turn the violent actualities of invasion into a simple ‘purchase’ from friendly and willing natives.[60] In the South Australian Court, a display from the governors of the Public Library, Museum and Art Gallery put it more baldly, juxtaposing Primitive life (1837) and Civilised life (1888) to illustrated colonial development ‘in which the native, with his canoe and living surroundings, forms a perfect contrast to the present, with its cultivated fields and domesticated animals’.[61]

Drouhet’s model, seen by tens of thousands of visitors, played a significant role at a particular historical moment prior to the crash of the 1890s that ended the long boom in fashioning and disrupting what ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ meant to its denizens. Its bird’s-eye view optic, itself reimagined and reinterpreted in Woodhouse’s lithograph, further juxtaposed with a lithograph of Melbourne in 1888, was part of the new genre of metropolitan representation that emphasised urban progress with an ‘illusionist thrill’.[62] John Hennings’s 1892 Cyclorama of Melbourne, commissioned by the government and inspired by Samuel Jackson’s panoramic sketch of Port Phillip in 1841 (itself viewed from the elevation of Scots Church at the corner of Collins and Russell streets, then in course of erection), was perhaps its nineteenth-century apotheosis.[63] Both Hennings’s cyclorama (though water damaged) and Jackson’s sketch survive today. But Drouhet’s model vanished, and his bit role in fashioning Melbourne’s historical consciousness was largely forgotten.

Afterlives: Melbourne 2020s

The Woodhouse lithograph was a kind of nostalgic prequel to the urban imaginary of 1888, simplifying Melbourne’s progress in the past rather than exaggerating it in the present. Traces of Drouhet’s city vision can still be seen in the lithograph, though its afterlife in the twenty-first century sees it regularly misconstrued as being an image made in 1838. The Royal Exhibition Building (REB) and Carlton Gardens were added to the World Heritage List in 2004, and visitors can now again access city views from its upper deck. How might Melburnians read the view from the dome in the present day?

In October 2022, the REB’s dome promenade was reopened to the public after renovations, including installation of a new lift, the Waygood Lift having been removed in 1889 when the exhibition closed. Access to the dome promenade can now be booked as part of a tour group, including museum entry, for the price of $29 for adults and $15 for children (in 1888, the charge to use the lift was sixpence for adults and threepence for children).[64] In an age before aeroplanes, skyscrapers and drones, the thrill and novelty of views at altitude for the nineteenth-century observer cannot be underestimated. That said, contemporary responses to the reopening of the dome promenade and the panoramic views thus obtained also respond to the novelty of a perspective that has been denied the public for over a century. Current-day visitors are taken past a ground floor exhibition on the history of the site and building before visiting the viewing platform. The views from the deck are variously described as extraordinary, spectacular and breathtaking. The deck is also promoted as a venue for weddings or cocktail parties (current rate $5,000 for two hours) as much as a place from which to ponder Melbourne’s fortunes, with the city a quirky backdrop for champagne and selfies:[65]

With an unmatched outdoor view of the picturesque Carlton Gardens and Melbourne’s whimsical city skyline, the Dome Promenade is a special and spectacular location that will make you feel on top of the world. If you’re looking for a special location for filming and photography, a unique venue to celebrate your wedding or corporate event, the Dome Promenade is the perfect space for you.[66]

Contemporary ways of viewing Melbourne continue to be enhanced—as they were in the nineteenth century—by new construction technology. Opened in 2007, the observation deck on the eighty-eighth floor of Southbank’s Eureka Tower (for a time the world’s tallest residential tower and tallest building in Melbourne) is promoted as the southern hemisphere’s highest observation deck. The giant Melbourne Star Observation Wheel opened briefly in Docklands in 2008, operating from 2013 until closing during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. In real estate terms, city views, now as much as in the nineteenth century, attract a premium.[67] From the city edge to Sunbury—where one modern-day street is simply named ‘City Views’—whether in full picture window framing or glimpsed obliquely through a telephoto lens, city skyline views in twenty-first century Melbourne are variously described as ‘mesmerising’ in Greenvale,[68] ‘spectacular’ in Glen Iris,[69] ‘sparkling’ in Seddon, ‘stunning’ in West Melbourne,[70] ‘inspiring’ in Surrey Hills,[71] and ‘dazzling’ or ‘knock out’ in Prahran.[72] Even ‘Partial city views!’ in Footscray attract an exclamation.[73] While some property advertisements hitch city views to a desirable cosmopolitan or exotic lifestyle (‘Hollywood glamour with breathtaking city views’ in Moonee Ponds),[74] the cachet of a city view has perhaps been shaped by evolutionary psychology in terms of prospect (a clear view of our surroundings) and refuge (a safer place to go) and a consequent symbolic equivalence of height with power and authority.[75]

The view from the recently restored dome promenade performs a similar role to the one experienced by visitors who had first viewed Drouhet’s model and then took the lift to the platform above. Melbourne laid out below in all its horizontal and vertical mass and scale now tempts one modern observer to marvel at development as progress, another perhaps to reflect on stolen land, or environmental impacts, or corporate power, or the inequities of a housing crisis in which many cannot afford rents but some live in million-dollar penthouses. The view south over central Melbourne, moreover, might inspire quite different responses to views to the west, north or east. While particular urban issues ebb and flow over time, what endures is the power of the vista to engender a charged relationship between the viewer and the view that invites a critical or emotional response.

A key difference between then and now, of course, is the symbolic meaning of the REB itself: in the 1880s, a contemporary, modern, monolithic palace of industry that dominated its environs; in 2023, a World Heritage site dwarfed by its neighbours. Where the REB of 1888 dominated the city, it is now, in many respects, diminished by it, the challenge of its buffer zone or World Heritage Environs Area (WHEA) being to protect the Outstanding Universal Value for which it was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2004. Both the views to or of and the views from have shifting cultural meanings, precisely because the site is challenged by the encroachment of the city that surrounds it. The most recent Draft World Heritage Strategy Plan for the Royal Exhibition Building & Carlton Gardens WHEA,[76] and a 2023 Heritage Council hearing into its recommendations, explored the management of height limits of future development in the buffer zone and the identification and protection of key views and vistas, whether aspect (inward looking) or prospect (outward looking). ‘Setting parameters for the extent and location of views (within the public realm at street and elevated levels within and outside the WHEA)’, according to the draft, ‘are increasingly relevant and necessary to meet contemporary practice’.[77]

The new Melbourne Museum opened on a site in the Carlton Gardens to the north of the REB in 2000, despite wide criticism of its likely impact on the view lines and heritage values of REB.[78] By the time of its 2002 nomination for World Heritage listing, the presence of the museum was rationalised as illustrating ‘continuity of function at the site, as a building also designed for exhibitions’.[79] With the museum building subsequently naturalised as an indispensable feature of the site, the 2021 draft urged the introduction of view controls to ensure that the silhouette of the REB was set against a clear sky backdrop when viewed from the Melbourne Museum forecourt.[80] The 2009 World Heritage Environs Strategy Plan had included division of the buffer zone into areas of ‘greater’ and ‘lesser’ sensitivity, effectively weakening planning controls in the latter zones, the most notable effect being approval of the twin towers of the Shangri-La and Sapphire-by-the-Gardens development at 308 Exhibition Street. Commenced in 2018, this skyscraper now rears up behind the otherwise relatively clear sky silhouette of the REB when looking towards the city from the museum: a ‘sky-parlor’ par excellence (Figure 10). In one sense, it might be argued, when viewed from the dome platform, it is simply the most recent in a long history of new built form in Melbourne—a continuum of examples that move the viewer in any historical period to exclaim that Melbourne is ‘coming on’. From a heritage sense, however, it is more problematic. Promoted by its vendor as ‘the crown jewel of the Melbourne skyline’, Sapphire-by-the-Gardens draws some of its prestige from ‘the grandeur of park front living, with unparalleled views across the UNESCO World Heritage-Listed Carlton Gardens’ (with no mention of the REB itself),[81] at the very same time as threatening those very values that underpin the site’s heritage listing (such as visual dominance in a low-scale and fine-grained setting).

Figure 10: View from Melbourne Museum forecourt looking south over REB towards Sapphire-by-the-Gardens / Shangri-La development. Photograph by author, March 2022.

Height limits are the result of ‘the interplay between the market, policy, and culture’,[82] while the notion of ‘protected vistas’ is further ‘loaded with shifting historical and political narratives’.[83] Some urban views are deemed too important to lose in the sense that they are taken to represent the culture or define the essence of a place.[84] The London View Management Framework, first introduced in 2007, encodes protections of a significant number of panoramas, linear views, river prospects and townscape views that define the historical character of that city. Most private property owners across Melbourne have no legal right to the protection of their city skyline views. The Shrine of Remembrance currently has better view protection than the World Heritage listed REB; vista regulations, first gazetted in 1962 and updated a number of times since, protect the view of the silhouette of the Shrine of Remembrance under the Shrine of Remembrance Vista Controls, which are incorporated into the Melbourne, Port Phillip and Stonnington Planning Schemes pursuant to section 6(2)(j) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987.

Conclusion

Melbourne itself was to be one of the most spectacular extramural exhibits at the 1888 Centennial Exhibition, the handmade product of an aspirational and materialist society. Monsieur Drouhet’s model of the incipient township, to which it was to be explicitly compared, confirmed this to be so. In an age when the bird’s-eye view of the city was partly inspired by the new vantage point of balloon flight, the juxtaposition of model (old Melbourne in miniature) and view (modern Melbourne in action) placed narratives of urban progress and pathology in the same urban conversation, at a moment when new technologies such as electricity and an underground sewerage system were poised to transform the frontier town into a modern metropolis. ‘Towns and cities’, observed pioneer British aeronaut James Glaisher in his Travels in the air (1871), ‘when viewed from the balloon, are like models in motion’.[85] In 2023, visitors to the REB’s upper promenade can marvel at the spectacular vertical growth of Marvellous Melbourne at a time when the skyscraper is still one of the most visible articulations of capitalist modernity. The REB’s status as a World Heritage site, however, has crucially shifted the optic of views to and from the dome. A buffer zone, after all, where intended to protect Outstanding Universal Value, ‘must’, ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) states, ‘not be a comfortable and reassuring fiction—it needs to be linked to practical and well rooted measures of protection’.[86] City views across Melbourne’s history have been much more than simply an index of urban growth; rather, they are a key to civic self-perception. In the process of balancing the opportunities of development with the need for preservation, the measure of any civilised society will always be its capacity to value its past in the headlong rush for the future.

Acknowledgements

Around 1987, I came across a file on Drouhet’s model in the City of Melbourne Town clerk’s correspondence files when I was researching my PhD thesis, and filed away a thought that one day I would write a piece on the subject. In 1994, while working at Monash University, I discovered that fellow historian Sheryl Yelland had also come across the tale of the Drouhet model, and we joined forces to undertake further primary research. As it happened, other projects demanded our attention, and we got no further than collating a manilla folder full of notes. Cancer took Sheryl in 1999, and my notes sat in a filing cabinet for over two decades until news that the Royal Exhibition Building’s viewing platform was to be opened to the public inspired me to write this article. Thanks (then and now) to R Bell, Alisa Bunbury, Tom Darragh, Kevin Gates, Peter Mansfield, Michael Meilak, AM Pobjoy, Margaret Rich, Charles Sowerwine, Christina Twomey, Roland Wettenhall, Dot Wickham and the two anonymous journal reviewers.

Endnotes

[1] George Henry Haydon, The Australian emigrant, London, 1854, in John Arnold (ed.), The imagined city: Melbourne in the mind of its writers, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1983, pp. 13, 15.

[2] The Exhibition Building became the Royal Exhibition Building at its centenary in 1980.

[3] Table Talk, 5 October 1888, p. 2.

[4] See, for example, his advertisement in the Ballarat Star, 11 January 1870, p. 4; letter to the editor, Argus, 25 January 1892, p. 6.

[5] Aube, France, Births, Marriages and Deaths, 1792–1912, Ancestry.com.

[6] Rendered Mr and Mrs ‘Draeigh’ in the PROV index to the unassisted passenger lists, along with their three daughters under 12, PROV, VPRS 947/P0000, Sep–Dec 1863.

[7] Argus, 17 November 1864, p. 3; 20 December 1864, p. 7; 5 July 1865, p. 8; 1 December 1864, p. 7; 13 October 1864, p. 7; 20 December 1864, p. 7; 18 October 1864, p. 8; 7 October 1864, p. 8; 6 January 1865, p. 3; 28 October 1864, p. 8; 1 October 1864, p. 8; 10 March 1865, p. 3; 4 November 1864, p. 8; 28 February 1865, p. 8; 4 March 1865, p. 7; 18 November 1864, p. 3; 21 November 1864, p. 8.

[8] See, for example, Proceedings in Insolvent Estate, Justin Drouhet, Melbourne, merchant, PROV, VPRS 759/P0000, 10927; Certificates of Discharge, Supreme Court of Victoria, Bradley Drouhet and Toche, PROV, VPRS 75/P0000; Proceedings in Insolvent Estates, Justin Drouhet Joseph Edgar Bradley Paul Toche; Melbourne; Merchants Co. partnership, PROV, VPRS 759/P0000, 10926.

[9] PROV, VPRS 422, Railways and Roads: Register of Correspondence (Inwards) 1873, No. 5791.

[10] WH Odgers, Circular No. 3410, 13 December 1870, PROV, VPRS 431, Unit 21: Engineer in Chief Letter Book 19 (May to Dec 1873), p. 192. Drouhet was listed in the triennial list of railways employees in the Victorian Government Gazette as a draftsman in the Chief Engineer’s Branch (1884, 1887, 1890).

[11] See, for example, Marieke Bloembergen, Colonial spectacles: the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies at the world exhibitions, 1880–1931, NUS Press, 2006; Marta Filipová (ed.), Cultures of international exhibitions 1840–1940: great exhibitions in the margins, Ashgate Publishing, Farnham, 2015; Alexander CT Geppert, Fleeting cities: imperial expositions in fin-de-siècle Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2010; Paul Greenhalgh, Ephemeral vistas: the expositions universelles, great exhibitions and world’s fairs, 1851–1939, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1988; Peter H Hoffenberg, An empire on display: English, Indian and Australian exhibitions from the Crystal Palace to the Great War, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2001; John McAleer & John M MacKenzie (eds.), Exhibiting the empire: cultures of display and the British Empire, Manchester University Press, 2017; Sadiah Qureshi, Peoples on parade: exhibitions, empire and anthropology in nineteenth-century Britain, Chicago University Press, 2011; Robert Rydell, All the world’s a fair: visions of empire at American international expositions, 1876–1916, Chicago University Press, 1984; Eric Storm & Joep Leersen (eds), World fairs and the global moulding of national identities: international exhibitions as cultural platforms, 1851–1958, Brill, Boston, 2022.

[12] David Dunstan, ‘Exhibitions’, in A. May (ed.), eMelbourne: the city past and present, School of Historical & Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, 2008, https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00542b.htm, accessed 24 July 2023. Other literature on Australia’s role in exhibitions includes Kate Darian-Smith, Richard Gillespie, Caroline Jordan & Elizabeth Willis (eds), Seize the day: exhibitions, Australia and the world, Monash University ePress, Clayton, 2008; Louise Douglas, ‘Representing colonial Australia at British, American and European international exhibitions’, Journal of the National Museum of Australia, vol. 3, no. 1, 2008, pp. 13–32; Anne Neale, ‘International exhibitions and urban aspirations: Launceston, Tasmania, in the 19th century’, in Marta Filipová (ed.), Cultures of international exhibitions 1840–1940: great exhibitions in the margins, Ashgate Publishing, Farnham, 2015, p. 251; Kirsten Orr, ‘A force for federation: international exhibitions and the formation of Australian ethos, 1851–1901’, PhD thesis, UNSW, 2006; Peter Proudfoot, Roslyn Maguire & Robert Freestone (eds), Colonial city, global city: Sydney’s international exhibition 1879, Crossing Press, Sydney, 2000; Jonathan Sweet, ‘Beyond local significance: Victorian gold at the London international exhibition, 1862’, in Keir Reeves and D Nichols (eds), Deeper leads: new approaches to Victorian goldfields history, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2007, pp. 185–202.

[13] ‘Melbourne Centennial Exhibition’, Age, 7 March 1888, p. 6.

[14] EG FitzGibbon, town clerk, to secretary for railways, 29 June 1888, PROV, VPRS 4025/P0000, Vol. 37, Nos. 732 and 773 [cannot be accessed due to conservation issue — last consulted in 1994]; secretary, International Exhibition 1888, to town clerk, Melbourne, 12 March 1888, 1888/555, PROV, VPRS 3181/316; secretary, Victorian Railways, to town clerk, 5 July 1888, 1888/1392, PROV, VPRS 3181/316. The files relevant to Drouhet’s model, dated 1888–89, were originally in VPRS 3181, Unit 317: ‘Festivities 1888–1889’, but at some point since I originally consulted them in the late 1980s they have been erroneously re-boxed in Unit 316: ‘Festivities 1887’.

[15] PROV, VPRS 3181/316. See also ‘Brief mention’, Herald, 20 July 1888, p. 2.

[16] ‘Deaths’, Argus, 23 June 1888, p. 1.

[17] Table Talk, 5 October 1888, p. 2.

[18] Musée des Plans-Reliefs, homepage, available at http://www.museedesplansreliefs.culture.fr/, accessed 13 January 2024. See also George A Rothrock, ‘The Musée des Plans-reliefs’, French Historical Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, 1969, pp. 253–256. Mayson’s physical relief model of the Lake District was created in 1875 based on ordnance survey maps. See Gary Priestnall, ‘Rediscovering the power of physical relief models: Mayson’s ordnance model of the Lake District’, Cartographica, vol. 54, no. 4, 2019, pp. 261–277. See also reference to a scale model of Melbourne’s water supply made by the Department of the Water Supply: ‘Irrigation and filtration’, Otago Daily Times, 9 April 1880, p. 2 (supplement); M Mikula, ‘Miniature town models and memory: an example from the European borderlands’, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 22, no. 2, 2017, pp. 151–172.

[19] Richard Aitken, ‘Celebrating gold’, Historic Environment, vol. 8, nos. 3&4, 1991, pp. 32–33.

[20] Museums Victoria Collections, available at https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/search?collection=Nordstr%c3%b6m+Mining+Models+Collection, accessed 13 January 2024; Victorian Collections, available at https://victoriancollections.net.au/items/5d9181e721ea671b24d46aff, accessed 8 January 2024.

[21] Secretary for lands and survey to town clerk, 9 July 1888, 1888/1441, PROV, VPRS 3181/316; Bride to town clerk, 10 July 1888, 1888/1440, PROV, VPRS 3181/316.

[22] J Drouhet to town clerk, 23 July 1888, 1888/1525, PROV, VPRS 3181/316; J Drouhet to town clerk, n.d. (received 30 July 1888), 1888/1708, PROV, VPRS 3181/316.

[23] FitzGibbon to Drouhet, 27 July 1888, PROV, VPRS 4025, vol. 37, no. 903.

[24] George Downing, foreman carpenter, to EG FitzGibbon, 5 October 1888, 1888/1946, PROV, VPRS 3181/316.

[25] David Dunstan, ‘Doing it all over again’, in David Dunstan (ed.), Victorian icon: the Royal Exhibition Building Melbourne, Exhibition Trustees in association with Australian Scholarly Publishing, Kew, 1996, p. 201.

[26] Official record of the Centennial International Exhibition, Melbourne, 1888–1889, Sands & McDougall Limited, Melbourne, 1890, p. 239; ‘Our Adelaide letter’, Daily News (Perth), 17 July 1888, p. 3.

[27] Official record, passim.

[28] ‘Melbourne gossip’, West Australian, 19 November 1888, p. 3.

[29] The pictures from the Victorian Loan Collection were by artist CG Robertson, see Official record, p. 651.

[30] J Drouhet, 12 September 1888, 1888/1767, PROV, VPRS 3181/316.

[31] Graeme Davison, ‘The culture of the international exhibition’, in Dunstan (ed.), Victorian icon, p. 18.

[32] See, for example, Graeme Davison, The rise and fall of Marvellous Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2004 (first published 1978), especially ch. 10.

[33] JS, ‘Gleanings from the exhibition’, Australasian, 15 December 1888, p. 48.

[34] ‘Exhibition notes’, Argus, 30 June 1888.

[35] A Melbourne Journalist, ‘The Centennial Exhibition’, Centennial Magazine, vol. 1, no. 1, 1 August 1888, p. 62.

[36] Dunstan, ‘Doing it all over again’, p. 201.

[37] ‘Growth of the city and suburbs’, Leader, 15 December 1888, p. 42.

[38] JH, ‘City and suburbs seen from two towers’, Argus, 8 May 1880, p. 4. See also David Dunstan, ‘The best view yet’, in Dunstan (ed.), Victorian Icon, pp. 87–90.

[39] ‘Advertising’, Argus, 24 May 1866, p. 1.

[40] ‘Advertising’, Herald, 3 May 1882, p. 4.

[41] ‘Advertising’, Argus, 6 June 1885, p. 3.

[42] ‘Advertising’, Age, 17 February 1887, p. 7.

[43] ‘Advertising’, Age, 17 November 1888, p. 15.

[44] ‘The birthday rejoicings in Melbourne’, Star (Ballarat), 28 May 1863, p. 4.

[45] Billy Nutts, ‘After many years’, no. II, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 22 June 1889, p. 11.

[46] Rohan Storey, ‘Skyscrapers’, eMelbourne: the city past and present, available at https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM01383b.htm, accessed 26 July 2023.

[47] Chairman, exhibition trustees, to B Benjamin, mayor, 28 February 1889, 1889/411, PROV, VPRS 3181/316; secretary, exhibition trustees, to City of Melbourne, 30 March 1889, 1889/581, PROV, VPRS 3181/316. Other models were presented to the exhibition, for example, those of the Jenolan Caves and Port Jackson. See ‘Melbourne exhibition. Presentation of exhibits’, Evening News, 8 March 1889, p. 8. On 24 December 1889, the exhibition trustees wrote to the railway commissioners asking for the models of Spencer and Flinders Street stations for the exhibition. Some remaining exhibits had been lent out, other more ‘useless exhibitions’ removed or auctioned off by the 1910s, while the ‘Picture of Early Melbourne’ was handed over to the premier. See PROV, VPRS 837.

[48] J Drouhet to mayor and councillors, 28 August 1888, 1888/1758, PROV, VPRS 3181/316.

[49] Engineer in chief, Railway Department, to EG FitzGibbon, 6 July 1888, 1888/1442, PROV, VPRS 3181/316.

[50] George Downing to town clerk, 25 March 1889, 1889/540, PROV, VPRS 3181/316; ‘Memoranda re purchase of photographs for Paris and Dunedin Exhibitions’, 25 November 1889, 1889/2364, PROV, VPRS 3181/316. See also Jock Phillips, ‘Exhibitions and world’s fairs—New Zealand exhibitions, 1865 to 1900’, Te Ara—the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, available at http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/photograph/45430/exhibition-buildings-dunedin-1889-90, accessed 1 June 2022.

[51] Paris Universal Exhibition 1889: catalogue of exhibits in the Victorian Court, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1889, p. 1.

[52] Examples of authors or websites that have reproduced the image as if it were from 1838, if not with ambiguity, include Michael Cannon (ed.), Historical records of Victoria. Foundation series. Volume Three. The early development of Melbourne, Victorian Government Printing Office, Melbourne, 1984, front endpapers: ‘Melbourne in 1838, from the Yarra Yarra’, lithograph in the National Library of Australia’; Miles Lewis, Philip Goad and Alan Mayne, Melbourne: the city’s history and development, City of Melbourne, Melbourne, 1994, p. 12: ‘Melbourne in 1838: From the Yarra Yarra: La Trobe Collection: State Library of Victoria’; Gary Presland, The place for a village: how nature has shaped the City of Melbourne, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, 2008, pp. 70–71: while the original attribution to the Drouhet model is just legible in the bottom left of the reproduction, the caption reads, ‘This coloured lithograph by Clarence Woodhouse shows Melbourne in 1838, from an imaginary highpoint on the other side of the Yarra River’; Jeff Sparrow, ‘Melbourne from the falls’, 9 July 2012, Overland, https://overland.org.au/2012/07/melbourne-from-the-falls/, accessed 2 June 2022: ‘This map from 1838 gives you a sense of how the city grew around the river’; ‘The oldest pictures of Melbourne’, Beside the Yarra: stories from Melbourne’s history, Blog, 25 January 2015, http://marvmelb.blogspot.com/2015/01/, accessed 2 June 2022; ‘Walking tours of Melbourne’, 2015, https://melbournewalks.com.au/ask-an-historian-online-class-activity/, accessed 2 June 2022; ‘Map of Melbourne 1838’, slide 16 of 45, Dr Susie Maloney (RMIT University), ‘Can Melbourne remain the (second!) world’s most liveable city?’, presented by 2018 ProSPER.Net Leadership Programme 12–16 November, 2018, https://www.slideshare.net/HannaatUNU/can-melbourne-remain-the-second-worlds-most-liveable-city, accessed 2 June 2022. Compare with more accurate contextualisation in Davison, The rise and fall, pp. 286, 287; Liz Rushen, ‘Nichola Cooke: Port Phillip District’s first headmistress’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 8, 2009, https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2009/nichola-cooke, accessed 2 June 2022; Sarah Ryan, ‘Bird’s-eye views of Melbourne’, Blog, 26 November 2013, State Library of Victoria (SLV), https://blogs.slv.vic.gov.au/such-was-life/birds-eye-views-of-melbourne/, accessed 2 June 2022.

[53] Weston Bate (ed.), Liardet's water-colours of early Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1972.

[54] Graeme Davison, ‘Picture of Melbourne 1835–1985’, in AGL Shaw (ed.), Victoria’s heritage, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1987, pp. 16–23.

[55] J Maier, ‘A “true likeness”: the Renaissance city portrait’, Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 65, no. 3, 2012, p. 717.

[56] Peter Burke, ‘Culture: representations’, in Peter Clark (ed.), The Oxford handbook of cities in world history, online edition, Oxford Academic, 2013. See also, F Buylaert, J De Rock & A Van Bruaene, ‘City portrait, civic body, and commercial printing in sixteenth-century Ghent’, Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 3, 2015, pp. 803–839; Juergen Schulz, ‘Jacopo de’Barbari’s view of Venice: map making, city views, and moralized geography before the year 1500’, Art Bulletin, vol. 60, no. 3, 1978, pp. 425–474.

[57] Nathaniel Whittock, The city of Melbourne, Australia, etching, Lloyd Brothers & Co, London, 1855, National Library of Australia, available at https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/1474920, accessed 13 January 2024; Melbourne Punch, 2 October 1856, p. 2, cited in Alisa Bunbury (ed.), Pride of place: exploring the Grimwade collection, The Miegunyah Press, Carlton, 2020, p. 129. See also Patricia Wilkie, ‘For friends at home: some early views of Melbourne’, La Trobe Journal, no. 46, 1991, pp. 61–68.

[58] SLV, accession no. H24502.

[59] Edward Noyce (lithographer), Collins Street—town of Melbourne. Port Philip, New South Wales, 1840, SLV, accession no. H18111.

[60] Official record, p. 239; ‘Our Adelaide letter’, p. 71.

[61] Official record, p. 239; ‘Our Adelaide letter’, p. 706.

[62] Davison, ‘Picture of Melbourne, p. 21 and passim. Davison mentions Drouhet’s model in passing, p. 25.

[63] Mimi Colligan, ‘Exhibiting old Melbourne: the cyclorama of early Melbourne’, in Canvas documentaries: panoramic entertainments in nineteenth-century Australia and New Zealand, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, 2022, pp. 187–196.

[64] ‘Going up! next floor, Dome Promenade!’, Lovell Chen, June 2019, available at http://www.lovellchen.com.au/lc/going-up-dome-promenade, accessed 24 July 2023).

[65] Kerrie O’Brien, ‘“Incredible attraction”: Exhibition Building dome opens for first time in a century’, Age, 4 October 2022.

[66] Museums Victoria, ‘Dome promenade’, available at https://museumspaces.com.au/spaces-for-hire/royal-exhibition-building/dome-promenade/, accessed 13 January 2024; Dome promenade, available at https://museumspaces.com.au/media/20957/mv_dome_promenade_events_brochure.pdf, accessed 13 January 2024.

[67] Kate Jones, ‘How much can a view add to a property’s value?’, Domain, 11 October 2021, https://www.domain.com.au/news/what-value-can-you-put-on-a-view-1094425; Samantha Landy, ‘Melbourne real estate: nine sky-high homes with the best city views’, Herald Sun, 2 January 2022, https://www.realestate.com.au/news/melbourne-real-estate-nine-skyhigh-homes-with-the-best-city-views.

[68] 27 Compute Street, Greenvale, Vic 3059, available at https://www.realestate.com.au/property-house-vic-greenvale-142630984, accessed 13 January 2024.

[69] 43 Florizel Street, Glen Iris, Vic 3146, available at https://www.realestate.com.au/property-house-vic-glen+iris-142631880, accessed 13 January 2024.

[70] 55/33 Jeffcott Street, West Melbourne, Vic 3003, available at https://www.realestate.com.au/property-apartment-vic-west+melbourne-142658520, accessed 13 January 2024.

[71] 973-975 Riversdale Road, Surrey Hills, Vic 3127, available at https://www.realestate.com.au/property-house-vic-surrey+hills-142639624, accessed 13 January 2024.

[72] 802/15 Clifton Street, Prahran, Vic 3181, available at https://www.realestate.com.au/property-apartment-vic-prahran-142624408, accessed 13 January 2024.

[73] 1208D/4 Tannery Walk, Footscray, Vic 3011, available at https://www.realestate.com.au/property-apartment-vic-footscray-142632596, accessed 13 January 2024.

[74] 8 Ngarveno Street, Moonee Ponds, Vic 3039, available at https://www.realestate.com.au/property-house-vic-moonee+ponds-142626548, accessed 13 January 2024.

[75] Andrea Bartz, ‘Why do we love the view from high above?’, Psychology Today, 19 September 2017. See also CI Seresinhe, T Preis, G MacKerron, ‘Happiness is greater in more scenic locations’, Scientific Reports, vol. 9, 4498, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40854-6.

[76] Review of the World Heritage Strategy Plan for the Royal Exhibition Building & Carlton Gardens World Heritage Environs Area, September 2022, available at https://heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/2019607_REBCG-Strategy-Plan_UPDATEDSEPTEMBER2022.pdf, accessed 1 August 2023.

[77] Ibid., p. 17.

[78] See, for example, ‘Builder named for new museum’, Age, 1 January 1997, p. 2.

[79] Environment Australia, ‘Nomination of Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens, Melbourne by the Government of Australia for Inscription on the World Heritage List’, 2002, p. 16.

[80] Ibid., ‘Section 8: views and vistas’, pp. 61–92.

[81] Sapphire by the Gardens, homepage, available at https://sapphirebythegardens.com.au/, accessed 19 June 2023.

[82] Igal Charney, Martine Drozdz & Gillad Rosen, ‘Venerated skylines under pressure: a view of three cities’, Urban Geography, vol. 43, no. 7, 2022, pp. 1087–1107.

[83] Tom Brigden, The protected vista: an intellectual and cultural history, Routledge, New York, 2019.

[84] Sara Gwendolyn Ross, ‘View corridors, access, and belonging in the contested city: Vancouver’s protected view cones, the urban commons, protest, and decisionmaking for sustainable urban development and the management of a city’s public assets’, Journal of Law, Property & Society, vol. 5, 2020, p. 115. See also Lucy Markham, ‘The protection of views of St Paul’s Cathedral and its influence on the London landscape’, London Journal, vol. 33, no. 3, 2008, pp. 271–287; Robert John Riddel, ‘How can a city keep its character if its landmark views aren’t protected?’, Conversation, 29 March 2016, https://theconversation.com/how-can-a-city-keep-its-character-if-its-landmark-views-arent-protected-55928.

[85] ‘“Appearance of the earth viewed from a balloon”, Glaisher’s “Travels in the air”’, Bendigo Advertiser, 23 April 1872, p. 2.

[86] ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) Position Paper in Oliver Martin and Giovanna Piatti (eds), World heritage and buffer zones, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2009, p. 23.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples