Last updated:

‘"Wayward", "immoral" and "evil": dispelling myths about Brookside Reformatory girls’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 21, 2023-24. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Erica Cervini.

Between 1887 and 1903, 257 girls were sent to the Brookside Reformatory, Victoria’s first privately run Protestant reformatory for girls. However, apart from newspaper articles and parliamentary reports that mostly shamed the girls and called them ‘wayward’ and ‘evil’, little is known about their lives. Using documents from Public Record Office Victoria and material from the State Library of Victoria and Trove, this article seeks to challenge assumptions about the Brookside girls by examining the lives of two inmates, Jessie Nairn and, to a lesser extent, Selina Wilson. After spending four years at Brookside, Jessie Nairn got married and had children and, by all accounts, was a loving mother. Other girls are mentioned to show their socio-economic circumstances and the cruel societal assumptions about them. This work is ongoing as I attempt to locate more records about the girls to challenge stereotypes and reinstate their dignity.

Introduction

Over 20 years ago, I wrote a thesis about Brookside Reformatory, the first private reformatory for Protestant girls in the colony of Victoria, as part of a master of education at the University of Melbourne. My interest lay in the history of the institution; as such, my thesis examined the Victorian Government’s motivation for setting up the reformatory and also that of Elizabeth Rowe, the reformatory’s head. It explained how the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act (1864) was revised to allow Brookside to exist, and investigated how the institution regulated the girls’ sexuality and work. The inmates themselves were anonymous: they were just numbers. For example, I noted that 10 girls had been transferred to Brookside, Cape Clear, near Ballarat, from the government-run girls’ reformatory at Coburg when it opened four days after Christmas in 1887; that seven girls had escaped in July 1889; and that, by the time it closed in 1903, over 250 girls had been sent there. The thesis barely mentioned the girls’ stories, yet I have always wondered about the exact reasons they were sent to Brookside, what their lives were like before the courts sent them there and what may have happened to them after they left the institution.

The Australian Government’s Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Abuse (2013–17) exposed details about children being ill-treated and sexually abused in places like Brookside Reformatory. That inquiry was partially responsible for prompting my renewed interest in the lives of the Brookside girls.[1] The stories that emerged during the royal commission, some of which were published in newspapers, were a powerful way of understanding what some children had endured in institutions and how authorities had tried to cover up their ill-treatment. The girls at Brookside also suffered mental and physical abuse. Knowing their stories shines a light on assumptions made about children from lower socio-economic backgrounds, especially those being raised by one parent, usually a mother, who were sent to such institutions. Piecing together their lives before, during and after Brookside unlocks and challenges the widespread belief that the girls who were sent there were morally bankrupt and promiscuous.

When I began researching the history of Brookside Reformatory, there was no Trove, the National Library of Australia’s repository of digital sources, including newspaper, which would have allowed me to identify copious articles. It was also difficult to locate neglected and criminal children’s records held at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) because I only had a few of the girls’ names. This current work has been made possible because Trove enables me to search for articles containing the words ‘Brookside Reformatory’ and other word combinations. To date I have located 93 articles. These provided some of the Brookside girls’ names, which, in turn, set me on a path to locating further newspaper articles, PROV records, police reports, death certificates and other documents. PROV has a wealth of records that can be searched online, including ‘neglected and criminal’ children’s records, many of which are now digitised. In addition, PROV holds parliamentary papers, letters and digitised shipping records that I have used for this current research, supplementing these with parliamentary reports held at the State Library of Victoria. The advent of digital research and online search tools have made this research possible, enabling me not only to name some of the girls who were sent to Brookside, but also to tell their stories, thereby showing as false the idea that they were ‘wayward’, ‘immoral’ and ‘evil’.

Elizabeth, Selina, Maud and Mabel

Brookside Private Reformatory for Protestant Girls, also known as Brookside Reformatory, was set up at a time when the Victorian Department of Industrial and Reformatory Schools (later the Department for Neglected Children) believed that children would be better served living in ‘family-like’ cottages in the country run by private individuals, rather than spending time in large, state-run institutions. George Guillaume, who was made head of the department in 1883, oversaw the opening of 11 private reformatories, including Brookside.[2] According to David McCallum, the idea of middle-class women running small reformatories ‘was seen as a solution to the failure of institutional care to solve the problem of wayward children’.[3] Patricia Grimshaw has argued that the cult of the middle-class family, which placed renewed emphasis on the family and home, was becoming dominant at this time.[4] Women, Grimshaw observed, were assigned a special place in the home as caretakers of morals and religion.[5] During this time, additional places were needed for so-called ‘neglected’ children because of the effects of the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act. An increasing number of children were now labelled neglected, resulting in overcrowded institutions, and authorities began worrying that overcrowding would ‘compromise whatever moral and educational roles these institutions could serve’.[6] The cottage system would, Guillaume hoped, counter the prison-like atmosphere of large, government-run institutions while at the same time teaching inmates neat and orderly habits in a homely, country atmosphere.[7]

‘Saving children’ was the aim of government authorities, including Elizabeth Rowe, head of Brookside; however, this desire was underpinned by assumptions and stereotypes about the type of children that needed ‘saving’. Such children were viewed as intractable; in the case of girls, it was assumed that they were involved in prostitution if out after dark. After visiting Brookside just once, T Rhodes, president of the State Children’s Fund in the 1890s, described the inmates as ‘ruddy buxom maidens’ and recommended that they remain in the country for as long as possible to rid them of their ‘moral typhoid’.[8] Newspaper articles often described Brookside girls as ‘wayward’, ‘immoral’ and ‘evil’. An 1899 report in the Argus, titled ‘Girls are vicious and morally corrupt’ detailed the escape and capture of seven girls from Brookside.[9]

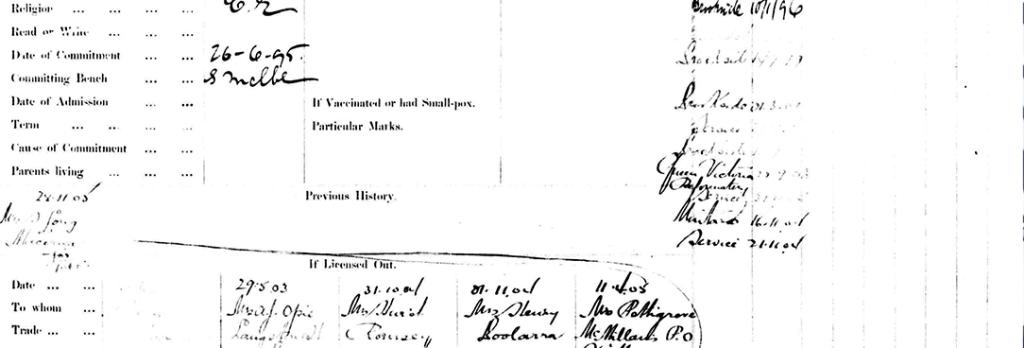

The girls’ records do not mention any involvement in prostitution; however, a harrowing case of sexual assault is recorded. In 1903, Elizabeth Branfield, aged 14, was charged with being a neglected child after being found wandering around Warngar. She was initially taken to Ararat County Gaol, where a male doctor examined her and reported that she was not a virgin and had been leading an ‘immoral life’.[10] In fact, Elizabeth had been abducted by Edward Jones Landsborough, a middle-aged man who had worked for her father. Her father was also accused of beating her, yet she was sent to Brookside (Figure 1).[11]

Figure 1: An article detailing Elizabeth Branfield’s case, which shows that, although she was a victim of sexual assault, there was no empathy for her. ‘Alleged Abduction’, Ararat Advertiser and Chronicle, 12 May 1903, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article267777333.

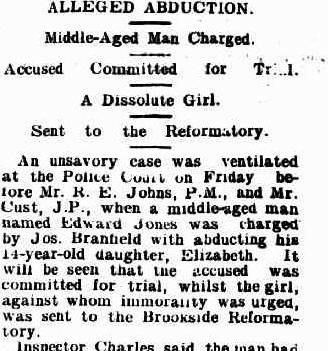

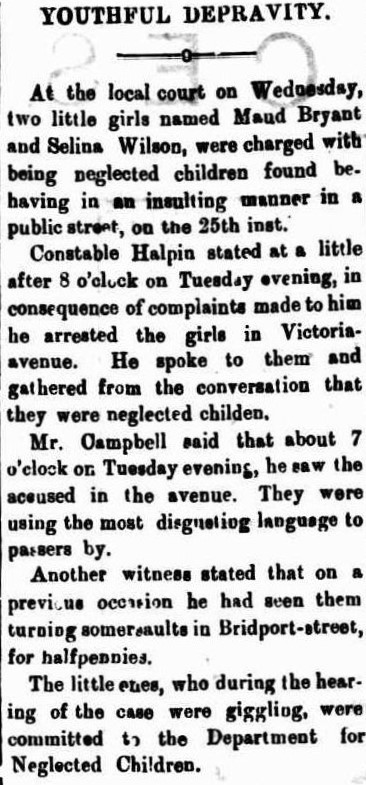

The case of Selina Wilson shows that girls were often assumed to be the instigators of ‘immoral’ acts. On a dark winter’s evening in June 1895, Constable Halpin spotted Selina and her friend Maud Bryant,[12] both aged eight, ‘behaving in an insulting manner on a public street’ in Albert Park, a beachside suburb in inner Melbourne. The children, according to the constable, were swearing and begging for money. The constable decided to march the girls to the watchhouse and lock them up ‘for their own safety’ (Figure 2).[13] The following day, Maud and Selina fronted the South Melbourne Court and were ‘charged with being neglected children’. Constable Halpin told the court that a witness had seen the girls doing somersaults for halfpennies while men watched on. Youths had taken the girls down a laneway and had ‘tampered’ with them, but I can find no evidence that the youths were apprehended for ‘tampering’ with eight-year-old girls.[14] Selina Wilson was sent to Brookside. She had previously been living with her brother, a wharf labourer, and his wife in Port Melbourne. A blank space appears in her record, held at PROV, after the ‘yes/no’ statement ‘parents living’ (see Figure 3).[15]

Figure 2: Newspaper report about Maud Bryant and Selina Wilson. ‘Youthful depravity’, Record (Emerald Hill), 29 June 1895, p. 3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108476145.

Figure 3: Selina Wilson’s second record, PROV, VPRS 4527/P0, 9323-22538; Girls convicted – Coburg Book, p. 184.

The Brookside girls’ records consistently show that inmates came from poor, inner-city or country families struggling to make ends meet during the 1890s depression, in which a third of breadwinners lost work. The girls lived in crumbling, overcrowded and, often, vermin-infested housing. Some had attended their local government school while others had worked as domestics or in factories. Many only had one parent; an absent father was common due to desertion, imprisonment or admission to a hospital or mental institution.

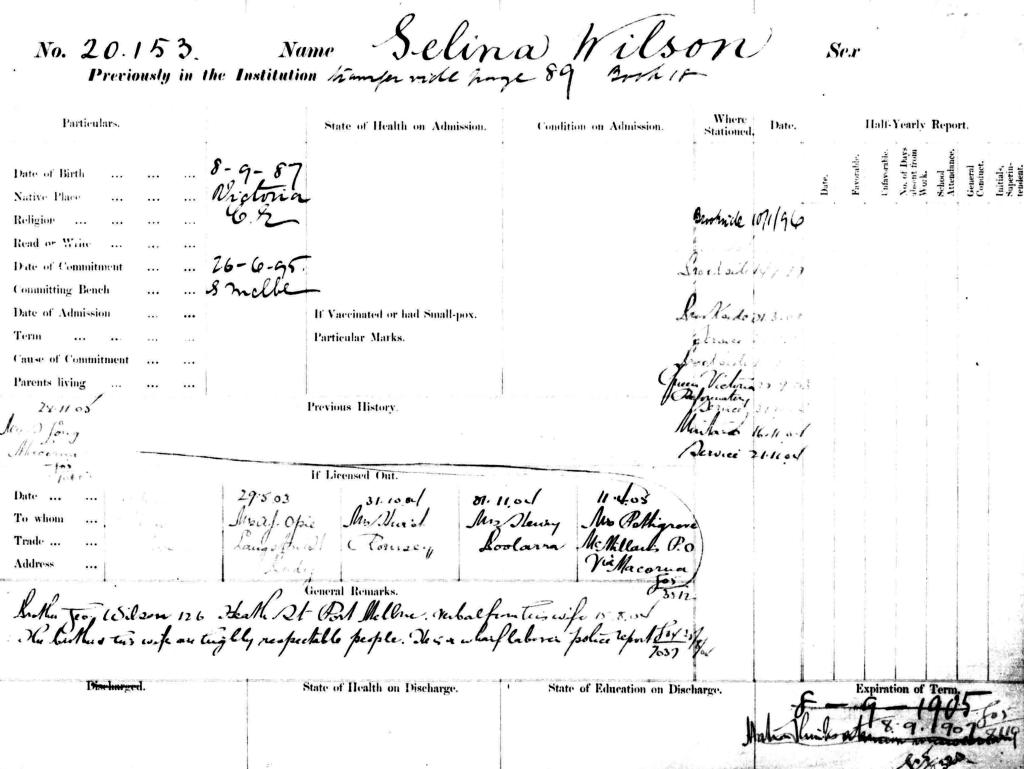

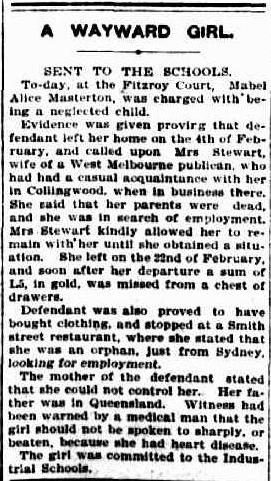

Given the lack of supporting parents’ pensions, single mothers had an almost impossible task keeping their children housed, clothed and fed. Mabel Masterton was sent to Brookside because she was deemed a neglected child. Fourteen years old, she had stolen a small amount of money from a hotel in West Melbourne to purchase clothes. She and her mother were living in poverty in Fitzroy; her father was in Queensland. Yet, rather than a victim of circumstance or poverty, newspapers described her as ‘wayward’ and ‘deceitful’ (Figure 4).[16]

Figure 4: Description of Mabel Masterton. ‘A wayward girl’, Herald (Melbourne), 8 March 1899, p. 1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article241873057.

Not ‘evil’ and immoral: Jessie Nairn

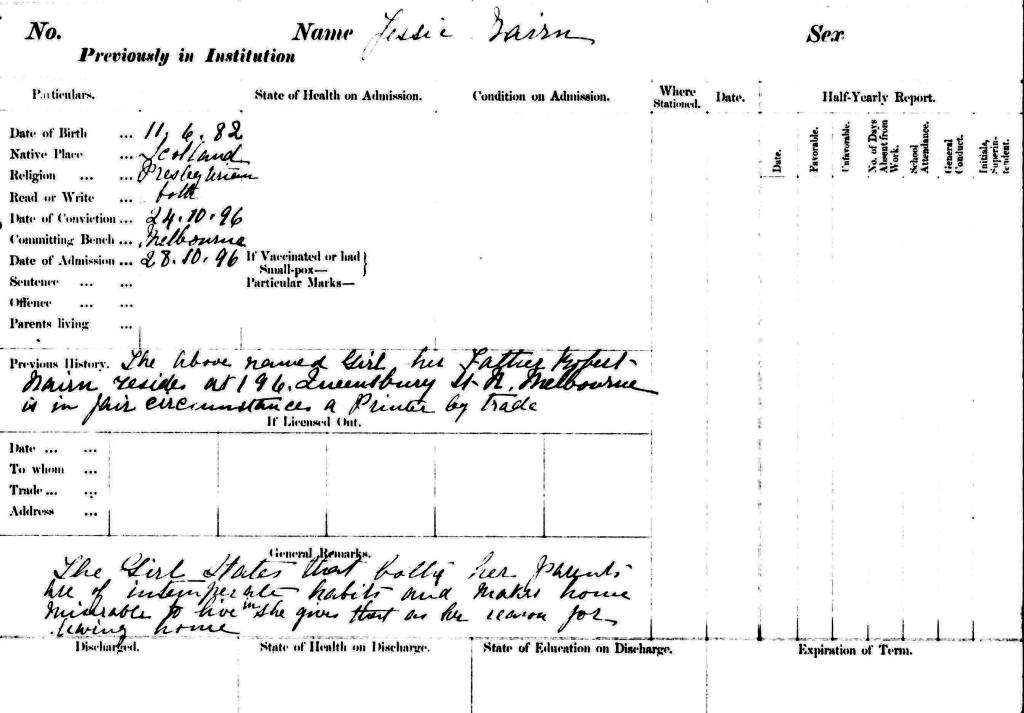

Jessie Nairn’s early life reflects that of many Brookside girls. She was two years old when she and her parents, Margaret and Robert, sailed on the steamship Chimborazo from Glasgow, Scotland, to Melbourne, Australia, in February 1885. They settled at 196 Queensberry Street, North Melbourne, where Jessie would remain an only child. Life in Melbourne was probably very different to what the family had dreamed of.[17] By 1895, family relationships were strained, and Jessie had run away. Jessie’s mother appealed in the Police Gazette for her 12-year-old daughter to return home. She was described as having a ‘stout build, fair complexion and hair and large blue eyes, and looking older than her twelve years’. She wore a spotted pinafore covering her dress and a straw hat trimmed with brown ribbon.[18] Upon being found, she was brought before the Melbourne bench where she was charged with being neglected. It is difficult to know exactly what was going on in the Nairn household, but Jessie told the Department for Neglected Children that her parents had ‘intemperate habits’ that made her homelife ‘miserable’ (Figure 5).[19] Her father, a printer, was often absent; he died in 1903 in Sydney Hospital.

Figure 5: Jessie Nairn’s second record, PROV, VPRS 4527/P0, 9164-18333; Girls convicted – Book 11, p. 214.

Jessie was initially sent to the girls’ reformatory at Coburg, an annex to Pentridge Prison, but was subsequently sent to Brookside, arriving there in early 1896. Brookside prepared inmates for service on farms and stations and to be the wives of selectors or farmhands. Jessie would have learned bread and candle-making and laundry work; she also would have done her own laundry and that of locals, earning Brookside 10 shillings a week. A new iron washhouse had been installed at Brookside, but Elizabeth Rowe ignored all labour-saving devices, such as wringers, because she believed that the girls had to get used to leading a simple farm life.[20]

Mrs Rowe employed a farm overseer and his wife to direct the girls in their farm work, which included feeding pigs, milking cows, clearing bush, cutting chaff for working horses and killing lambs. In addition, Jessie and the other inmates tended 1,000 sheep and 50 head of cattle grazing on 15,000 acres. Vegetables were grown on 15 acres. There was little time for formal education in reading and writing, and these skills were not considered important for farm girls anyway. Dr Dowling, who visited Brookside, commented: ‘These poor girls can never expect to attain any but a very humble sphere of life or duty and it is wise to and right to train them accordingly for country homes and farms where this kind of work will fall upon this lot.’[21]

After a period of learning farm work, cooking and sewing, Jessie was sent out to service; she was sent out four times to isolated farms across Victoria, returning to Brookside between each placement. It is unclear how Jessie and the other girls were treated on the farms, because it appears that no reports were written, except for the odd comment in annual reports that a girl’s service had been terminated because she was ‘not following directions’. I cannot find any mention in the archives of authority figures visiting the girls to ensure they were being properly treated. This is unsurprising given that the reformatory itself only had casual inspections.[22]

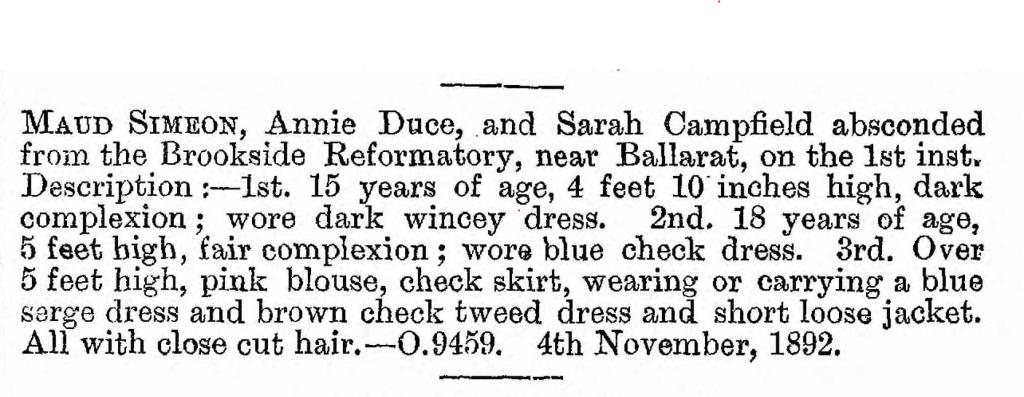

The work on isolated farms was interminably tough and it was the same soulless and brutal work at Brookside. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that Jessie and six other girls, including Selina Wilson and Mabel Masterton, aged 12–17, escaped Brookside in July 1899. This was not the first time that girls had tried to escape, and some teenagers, like Annie Duce, had escaped multiple times.[23] The Victorian Police Gazette noted that Annie had ‘close cut hair’, a punishment for girls who tried to escape the reformatory (Figure 6).[24]

Figure 6: The description of Annie Duce in the Victoria Police Gazette mentions her ‘close cut hair’.

Jessie and the other girls were eventually found, frost-bitten and starving, by Mounted Constable Steven, who accompanied them on a 24-kilometre coach ride to Ballarat police station. There they told Constable John Clifford that flogging with a heavy strap was meted out to girls who showed signs of insubordination. In his report, the constable described the strap as a ‘portion of discarded belly-brand’.[25] Clifford observed that two of the girls had marks on their arms consistent with a recent severe flogging.[26] Despite the constable noting other punishments and seeming to believe the girls’ stories, Jessie and the others were returned to Brookside and denounced in the press for their ‘evil ways’.

A letter held at PROV confirms some of the disturbing disciplinary techniques used on the girls. Dr Raymond Fox, a medical practitioner who visited Brookside fortnightly and also cared for Mrs Rowe, defended the practice of tying the girls’ hands behind their backs as a form of punishment. In 1899, in a letter to Thomas Millar, then head of the Department for Neglected Children, Dr Fox explained why he routinely ordered this punishment: ‘One of the great troubles we have to deal with is the extremely hurtful habit of masturbation. We have constantly been on the outlook for it for the individual’s sake as well as for the danger of her teaching it to younger members.’[27] How Dr Fox knew if the girls had masturbated or not is puzzling and disturbing. He even suggests in the letter that Jessie, Selina, Mabel and the others had escaped Brookside to masturbate. Given the mythology surrounding masturbation at the time, girls who broke rules were accused of ‘moral insanity’ and branded sexually wicked.

In 1900, Jessie turned 18 and left Brookside. It is unclear what she did immediately after she left but she may have worked as a domestic, as that was her training at the reformatory. In 1904, at the age of 21, she married Australian-born Archibald Kidd, a 27-year-old labourer, in the inner-northern suburb of Fitzroy. They settled in North Melbourne, the suburb of her childhood. Later that year, Jessie gave birth to her first child, Margaret, who would die 15 years later of pneumonic influenza.[28] Another daughter, Jessie Elizabeth, arrived in 1905.[29] A third daughter, Mary Ellen, born in February 1907, died less than 12 months later in January 1908, the same year that Jessie’s mother died.[30] Louisa Isabel, Jessie and Archibald’s last child, was born in 1911.[31] Jessie lived in North Melbourne the rest of her life, dying at her home, 64 Abbotsford Street, in 1943.[32] She is buried in the Coburg Cemetery.[33] Archibald would be buried with her after he died in 1954.[34] Jessie had five grandchildren at the time of her death. From what I can glean about her life, she was none of the pernicious labels attached to her in her neglected children’s record and in newspaper reports. There is no record of Jessie being in trouble with the law after leaving Brookside. Her death notices suggest that she was well loved.

Conclusion

Jessie, Selina, Mabel, Elizabeth and most of the other girls sent to Brookside were victims of circumstance—of poverty. Some committed crimes such as stealing, which reflected the seriousness of their low socio-economic status. For most, their ‘crime’ was that they came from impoverished families, many headed by a single mother. They were readily described as ‘wayward’ and ‘evil’ because they did not conform to standards of middle-class ideas of female propriety and were incarcerated. These girls, some as young as eight, deserve to have their dignity reinstated. An empathic appraisal of their circumstances, such as conducted here, is one way to achieve this.

Endnotes

[1] Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, homepage, available at https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au, accessed 18 January 2024. Stories of abused children are included on the website.

[2] ‘The death of George Guillaume’, Age (Melbourne), 25 April 1892, p. 5.

[3] D McCallum, Criminalizing children: welfare and the state in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017, p. 68.

[4] P Grimshaw, ‘Women and the family in Australian history’, in E Windschuttle, (ed), Women class and history: feminist perspectives in Australia 1788–1978, Fontana/Collins, Sydney, 1980, p. 4.

[5] Ibid.

[6] McCallum, Criminalizing children, p. 68.

[7] See, for example, Victoria, Department of Industrial and Reformatory Schools, Report of the Secretary for the Year 1885, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1886, p. 8, https://webresource.parliament.vic.gov.au/VPARL1886No77.pdf, accessed 3 February 2024. Also see George Guillaume’s letter, Herald (Melbourne), 3 June 1884, p. 4.

[8] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, K8075, Rhodes, T, ‘How to treat the children: interesting notes on Victorian children’, 1 June 1894.

[9] ‘Girls are vicious and morally corrupt’, Argus (Melbourne), 14 August 1899, p. 6.

[10] ‘Accused committed for trial, a dissolute girl, sent to reformatory’, Ararat Advertiser and Chronicle for the Stawell and Wimmera District, 12 May 1903, p. 2.

[11] Ibid.

[12] The court heard that Maud’s mother had frequently been before the courts for drunkenness. She lost custody of her child. There is no mention of a father in Maud’s records. As she was Catholic, she was sent to the Convent of the Good Shephard, Abbotsford, established in 1863. There is no further trace of Maud in the archives.

[13] ‘Youthful depravity’, Record (Emerald Hill), 29 June 1895, p. 3.

[14] ‘Neglected children: a dark picture’, Herald (Melbourne), 26 June 1895, p. 1.

[15] PROV, VPRS 4527/P0, 9323-22538, Girls convicted – Coburg book, p. 184, Selina Wilson’s ward record. So far, I have identified the records of 41 girls who were sent to Brookside.

[16] ‘A deceitful girl’, Age (Melbourne), 10 March 1899, p. 7; Victoria Police Gazette, 1899, Mabel Masterton, image 79 (missing child), available at ancestry.com.au.

[17] PROV, VPRS 4527/P0, 9323-25538, Girls convicted – Coburg book, p. 209, Jessie Nairn’s second ward record. See also, Registry of Births, Deaths, Marriages (NSW), Robert Nairn’s death, record 5740/1904.

[18] Victoria Police Gazette, 1895, Jessie Nairn, image 5 (missing child), available at ancestry.com.au.

[19] PROV, VPRS 4527/P0, 9164-18333, Girls convicted – book 11, p. 214, Jessie Nairn’s first ward record. There are two entries on Jessie.

[20] Victoria, Department for Neglected Children and Reformatory Schools, Report of the Secretary, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1800. See also Farm Life for Reformatory Girls, Being an Account of a Visit to ‘Brookside’ Private Reformatory with Editorial Comments, Melville, Mullen & Slade and ML Hutchinson, Melbourne, 1890 (reprinted from Age, 1 January 1890).

[21] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, K8075, 1899, report on the health of Brookside and St Ann’s inmates by Dr Dowling.

[22] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, K7266, Inspector Evans, report on Brookside, 26 July 1888. Evans sent a letter to the Department of Education requesting that Brookside be occasionally inspected by him while he did rounds at local primary schools. Also see Alice Henry’s critical report on Brookside, Argus, 2 August 1899, p. 4.

[23] Two records exist for Annie Duce. See Ward Registers, PROV, VPRS 4527/P0, Girls convicted –Coburg, 9164-18333, pp. 97, 146.

[24] Victoria Police Gazette, 1864–924, 22 March 1894, Annie Duce, image 198, available at ancestry.com.au.

[25] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, K8075, Constable John Clifford, Ballarat Police, report on escapes from Brookside, 14 July 1899.

[26] Ibid.

[27] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, K8075, letter from Dr Raymond Fox to Thomas M Miller, head of the Department of Neglected and Criminal Children, July 1889.

[28] Information about this family is available at ancestry.com.au, which is free to access at many local libraries and at state libraries. See ‘Margaret Kidd, 1904–1919’, https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/12958664/person/12777377593/story, accessed 3 February 2024.

[29] See ‘Jessie Elizabeth Kidd, 1905–1967’, https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/12958664/person/12203206150/story, accessed 3 February 2024.

[30] See ‘Margaret Burns, 1855–1908’, https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/12958664/person/12806050174/story, accessed 3 February 2024.

[31] See ‘Louise Isabel Kidd, 1911–1988’, https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/12958664/person/-149970343/story, accessed 3 February 2024.

[32] BDM 477/1943, death certificate for Jessie (Nairn) Kidd. Her certificate lists her children, as does a death notice in the Age, 14 January 1943.

[33] Cemetery records and headstones transcriptions, 1844–1997, Victoria, Australia (Jessie Kidd), available at ancestry.com.au.

[34] Cemetery records and headstones transcriptions, 1844–1997, Victoria, Australia (Archibald Kidd), available at ancestry.com.au.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples